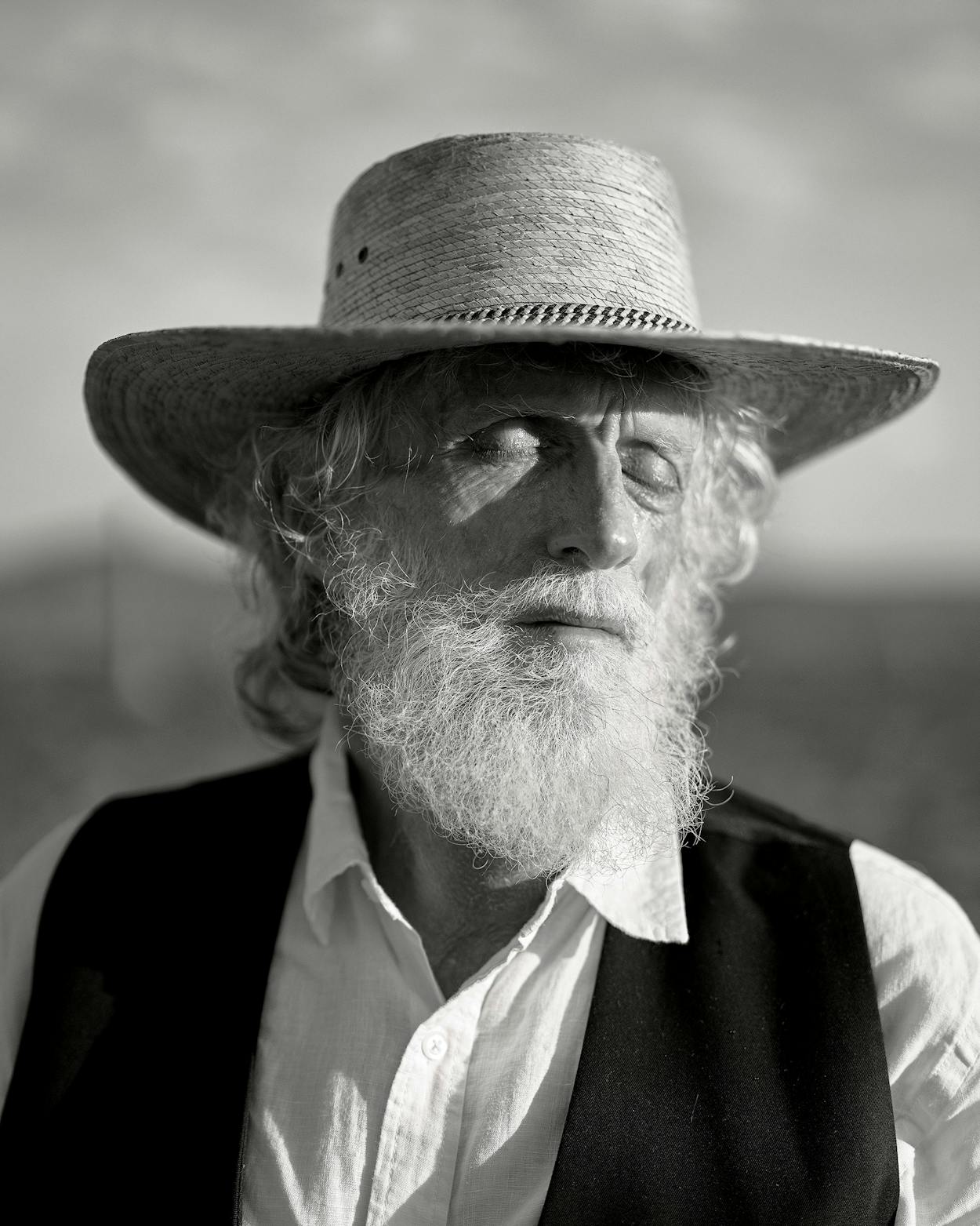

James Magee pauses with his fork poised above his huevos rancheros. He is considering the question of what it is that artists do. Magee’s eyes are pale blue, and his frame is rawboned and valleyed. His longish hair and beard are white-white, and he has Lincoln-like hollows at his cheekbones and brow. An oompah-heavy norteño waltz chugs cheerfully on the radio at El Paso’s L&J Cafe. “Everything could be the last thing you could do,” he says finally, in his patient way. “Every encounter with a person could be the last. As an artist, I just let it all out, as much as a person can.”

Magee, 75, has lived in El Paso since 1981. He is a maker of objects, buildings, paintings, texts, and sculptures, which relentlessly occupy his days. He oversees several shop assistants and travels nationally for performances of his aural and written pieces. He works out of a shop and several studios scattered near downtown and also maintains a museum and two residences, one of which he shares with his partner, the writer and actress Camilla Carr. Yet one project remains central and incomplete: “The main effort is to get the Hill done,” he says. “It’s all incidental to the Hill.”

Located on more than two thousand rural acres about an hour and a half from El Paso, the Hill is Magee’s masterwork. Except for at a few concerts that have been held on the property, only about two hundred visitors have seen the Hill, in Magee’s estimation. Workers have to prepare the site before it is shown, which can take a couple days, and no more than a handful of guests can view it at a time. “For people who are ready and receptive to James Magee, if you go to the Hill with him, you will forever divide your life into two parts: before the Hill and after,” Richard Brettell said shortly before his death in July. Brettell, an art scholar and former director of the Dallas Museum of Art, wrote extensively about the Hill, which he first saw in 1988. “It’s transformative,” he said, “unlike anything else.”

On this December day, there are other places to see and other considerations to make before visiting the Hill, so after breakfast we clamber into our dog-worn, caliche-dusted Tundra with Magee. My husband, Michael, drives. “How many miles?” Magee asks as he peers around the vehicle’s interior. “More than 260,000,” says Michael. “It’s driven to the moon.” “A fine truck!” Magee declares. The chill morning does not invite pedestrians, and when we pull up to Magee’s shop—a nondescript masonry building in an industrial neighborhood of wholesale dealers and junk stores—no one’s around.

Inside is Magee’s vast inventory of materials, organized in heaps on the floor: scrap metal, rusted steel, broken glass, car parts, wood. Worktables hold drills, pulley parts, spigots, air hoses, a jack, and chains. A sculpture in progress, intended for the Hill, sprawls on the floor, while works not meant for the Hill have been installed on the walls or hung in storage racks. A chair contraption dangles from a gantry so Magee can be hoisted to access a work from above or be raised as a sculpture gains height. Steel boxes hold detritus behind glass. Brightly colored metal panels angle jauntily next to one another. Surfaces of other pieces are pebbled and distressed with rust. The shop’s rooms and contents are a busy carnival of industry and information, nearly overwhelming in the array of colors and textures.

Adair Margo, who was the chair of the President’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities during George W. Bush’s terms, is familiar with the topsy-turvy sensation associated with encountering Magee’s work and spaces. She recalls visiting his former studio, located in an El Paso salvage yard, shortly after meeting him in about 1986. “I’d never seen anything like it,” she says. “I wasn’t sure what I was seeing, but I knew it was significant. I’ve only come to understand the work over a long time.”

Magee waits and watches as we gawp. We pause at a long wall piece, perhaps eight feet across, with a honeycombed grate affixed to one end of a baby-blue guardrail. On the other end, a wide ribbon of red metal punctuates a field of glass shards and yellow metal inset in a steel frame. Magee walks over and retrieves a folded paper tucked behind the sculpture: his works’ titles are written in poetic free verse, which he occasionally sings, chants, and recites to viewers. “You must get close,” he says, and draws us in nearly nose-to-nose. He begins the title, half-singing. “Bear down on it or tear it up in anger,” he keens. “Yet who owns this hillside house anyway?” I find out later that this title is 37 lines long; it takes Magee about a minute to perform. And in that time, in which the seconds unfurl with the deliberation of a cat as it stretches, the background of the shop blurs and fades from sight. In this building, with its crazy crowded depository of art, objects, and piles of stuff, there is nowhere to look except into Magee’s eyes.

Everyone’s life has chapters—childhood, school, career, marriage, and so on—but Magee’s life has had more than most. He’s unusually given to following his interests, and his trajectory to El Paso wasn’t linear. He grew up in Fremont, Michigan, the son of a car dealer and a homemaker. Though no one in his family was an artist, he became absorbed by the images in a book at his house, Janson’s History of Art, and for a time he took drawing lessons from a local artist. He went on to attend a small Presbyterian college, also in Michigan, studying history and French.

After a summer spent backpacking in West Africa, Magee enrolled in law school at the University of Pennsylvania, where he soon realized that grades were based on tests and not time in the classroom. “I didn’t have to show up to class,” he says. “I showed up only for finals. So I rented a storefront as a studio, and I painted.” After he graduated from Penn, he assisted two sculptors in Paris, followed by a stint as a Pinkerton guard in Boston. Then on to New York City, where he worked for the city’s planning commission by day and spent nights in a Staten Island junkyard, making sculptures and singing his titles into empty industrial milk containers. He also explored Manhattan’s bathhouses and gay bars, places with names like the Anvil or the Mineshaft. “I’ve lived a very variegated life,” he says. “I didn’t so much come out as I came into myself. I’ve had boyfriends and girlfriends, and it’s not any different.”

In 1973 Magee bought a former chicken coop in upstate New York and made art in the coop’s large open space. To create income, he was involved in a dizzying and often simultaneous array of jobs throughout the seventies. He worked with the Quakers and the United Nations on bills concerning the right to conscientiously object to military service. Later, he continued working with the UN, analyzing treaties related to the Law of the Sea, often traveling. Magee likewise drove a cab, built stage sets, and learned to weld. He also occasionally volunteered as a personal caregiver to a dying man in New York City. “That was my cycle, which was absolutely insane,” he told an interviewer from the Smithsonian Institution, which began archiving his papers in 2016. “You know—UN, Home for the Dying, gay bar, sex club, gay bar—gigantic, four floors. And then by one or two in the morning, St. Mark’s Baths and then home to bed. Then wake up with six hours of sleep and go to the UN. I could not keep this up.”

Magee fell into a depression. All along, he had seriously pursued art in the chicken coop, where his objects and floor pieces consumed the available space. Some of the work may have reflected his emotional state. “He had built a crucifix in New York, but nobody came to see it,” says Margo. “He was doing dark work—tortured. He’d done this piece called Ozzie and Harriet, which was obviously human figures but with animal teeth, beaten into the ground.” The disturbing nature of Magee’s art seemed at odds with the gentle man Margo knew. “There’s a pressure in the art world to do dark work because people see it as more significant,” she says. “It’s much harder to do things filled with light—you’re written off as sentimental.”

Change was percolating. In 1976, while in the throes of depression, Magee had sent a film of his work to friends who were monks in France. One wrote to Magee afterward, urging him to “look at God’s handiwork.” Magee duly erected a tent outside the chicken coop, where a remarkable thing happened. Or, rather, a remarkable person happened: Annabel Livermore. “She came into me, fully formed,” he says. She began painting blueberry bushes. “It wasn’t anything I had to tap into. She was there.”

Livermore, who, like Magee, now lives in El Paso, is an older retired librarian from the upper Midwest. She’s a painter of landscapes, memories, and dreams. She could be called a personality, or Magee’s alter ego, but that taxonomy is anemic. She’s not a pseudonym or a cute trick to sell art. Livermore has dimension, talent, and interests all her own. “She’s been a close friend for more than forty years,” Magee says. “I had to figure out what God’s handiwork was all about. Annabel led me to what that’s about. I owe her my life.”

Livermore does not do in-person interviews or appear at art openings. She maintains a studio near the house that Magee shares with Carr, which is also full of Livermore’s work. She’s posted major shows at Yale University and at the Santa Monica Museum of Art and El Paso Museum of Art, among other institutions. While Magee’s art is abstract and unpeopled, Livermore’s is wildly colorful and figurative. Oranges and yellows feature prominently: a golden fish surveys the golden grasses surrounding its pond; three figures row a fanciful golden canoe.

Magee introduced Margo to Livermore’s work in 1986. “We went to his house,” Margo recalls. “He said Annabel lived in the boiler room and she painted, and Jim made these really ornate frames for her. I fell in love with the paintings right away.” Livermore’s work, according to Margo, is the embodiment of the people and places Magee knew as a child. Her paintings of flowers, rivers, and figures allow Magee to reveal the joyfulness of his being. He once told Margo that talent rises to the top but too often gets crushed underfoot. “He was probably talking about his own experience,” Margo says. “Annabel picked up watercolors, and by looking at nature and painting the people he loved, she’s healing him.”

Around 1990, moved by the plight of a hospitalized friend, Livermore established the Annabel Livermore Flower Fund, which placed blooms in patients’ rooms at the University Medical Center of El Paso. She later designed the hospital’s chapel, called a meditation room, and created the artwork within (the Flower Fund no longer supplies flowers for patients’ rooms but continues to supply flowers to the chapel). In 2003 Livermore spent several months making plein air paintings on a New Mexico ranch in an area that conquistadors called Jornada del Muerto, or Journey of the Dead Man. There, she had a revelatory experience, making a ten-panel series of brilliantly lava-colored paintings called “Journey of Death as Seen Through the Eyes of a Rancher’s Wife.” These so moved Magee that he was compelled to do something radical for his friend.

“I have my own Annabel Livermore museum,” he says. He’s directed us from his workshop to a small adobe house, and he’s fiddling with the lock on the door. “I’m the curator and the accountant, and I mop the floors.” The space inside has gallery lighting and seats from which to regard the work. Livermore’s ten Rancher’s Wife paintings hang here, abstracted landscapes that hum with the energy of bursting fire wheels, whirling dust devils, and big bang light forms that explode above a mountain range. The circles and swirls and colors repeat across the paintings like incantations. Each painting builds upon the one before it, Livermore documenting something that is at once earthly and magical, beautiful and ferocious, familiar and beyond our ken. We do not talk for some time. “It’s all glory, glory, hallelujah,” Magee eventually says from his stool in the corner. “Sometimes God’s handiwork is as terrifying as it is wonderful.”

When you get to know someone, where do you start? How much will you ever know a person in all their faults and shades?

Not far from the museum is a compact house where Magee often stays alone. An unfinished sculpture of a fish anchors the front yard. Someday, Magee tells me, there will be a man, the biblical Jonah, emerging from its mouth. A sign on the house faces the sidewalk: “Forgive.” “The sign is for everyone who sees it,” he says.

The little house has just two rooms. In one, a desk, a bed, and bookshelves full of poetry share space with a simple kitchen. The other room is the studio of artist Horace Mayfield, the second of Magee’s adopted personas, who was prolific in the decade following Mayfield’s arrival in the early nineties. For the past seven years, Mayfield has worked with Livermore on a long-term project revisiting the Old and New Testaments in scrolls. Magee delivers this information—that two incorporeal artists have an ongoing collaboration—matter-of-factly, as though this arrangement were mundane.

“The landscape of his thoughts is enormous,” Richard Brettell said of Magee. “How do you put him in one place? Is he a writer, is he an artist, is he a man, is he a woman, a painter, a sculptor? He defies efforts to catalog.” Of one thing Brettell was certain: “He is among the greatest artists of my generation. He’ll be incredibly famous after he dies.”

The idea for the Hill came to Magee in 1977, he says; the only question was where to build it. He initially figured he’d locate more land in upstate New York so he could continue working with the UN, but then he recalled liking Texas when he’d worked a stint in the Permian Basin oil fields. A move, too, would end what Magee called the “merry-go-round” of frantic activity that absorbed and depleted him in New York. In 1981 he returned to Texas. “That was the big rip,” he says. “I scouted a long time for the right place, from Brownsville up to New Mexico. With El Paso and Juárez it was love at first sight. I’ve lived half my life here now.”

After settling in El Paso, Magee bought a hundred acres and started work on the first of the Hill’s four buildings. Gradually, word crept out that Magee was, as he says, “making big things in the desert.” He showed the work in progress to a few collectors and aficionados from Texas and elsewhere. They saw value in it, and these advocates eventually created the Cornudas Mountain Foundation, named after the Cornudas range, which helps financially support the endeavor. The acreage has grown to more than two thousand. (Before the pandemic, visits to the Hill could typically be arranged by contacting the foundation, which asked for a $250 contribution per guest or $400 per couple.)

Fifteen of the Hill’s forty-five planned rock columns are done. Three buildings are complete, and the fourth may be finished by 2030. The project has now continued for nearly forty years: Magee and his crew can go only as fast as their budget and stamina allow. The Cornudas Mountain Foundation knows what’s at stake. “This has a definite end if I don’t end before it does,” Magee says. “The fourth building is the conclusion. But if I die before it is finished, the work ends that day.”

Other artists have made large-scale work amid the Texas landscape—Donald Judd’s permanent installations in Marfa come to mind. Judd had formal concerns about materials, space, and light, but the urges behind Magee’s work and whatever meaning can be ascribed to it are much more fluid. “It’s completely personal,” he says of the process. “All of it is mysterious to me.”

As we roll along on our way to the Hill, Magee rides shotgun in the truck. The conversation is buoyantly far-flung. What’s a good, cheap hotel in Mexico City? Dark matter and dark energy—that’s the frontier of science. Oh, the porn theater’s advertising new management. Things are looking up! Pomegranates, the El Paso Salt War of the nineteenth century, his beloved Honda Element. Wonder Bread, art, fizzy water. Due to an illness, Magee is a double-leg amputee, and to relieve an ache he removes the left prosthetic, which he calls Sun Chaser. (The right one is Water Blade.) He loves the poetry of beat writer Harold Norse. He favors early medieval music. He doesn’t keep up with current trends in art or artists. “My view of everything is narrow and maybe antiquated,” he says. “Sometimes I’ll look at an art journal and be amazed and surprised, but I don’t seek it out. How do you get better than the Etruscan tomb paintings? You really can relate to them.”

The city’s car lots and taco joints recede. The land opens up. The sky is cloudless, the air is sharply dry, and the light is crisp. Only yucca and greasewood burden the contours of the land. Eventually we arrive at a locked gate and bump down a private ranch road. Before us, four rectangular rock buildings appear on land that subtly swells. The buildings face one another, and they are blond and red stone, sourced nearby. A raised rock walkway links the buildings, the interiors of which are installed with site-specific sculpture. Giant rock columns encircle the group of buildings, but at a distance. The site is not a church, but its deliberate placement and austerity amid the nothingness and everythingness of the desert feels holy. This is the Hill.

Magee rolls down his window and greets his assistants, two brothers from Juárez, Juan and Pepe Muñoz, who’ve been with him for more than a decade, and they chat warmly together in Spanish. (A third longtime helper, also from Juárez, has been hospitalized with a heart attack, and Magee will visit him the following day.) “These works have been done by old men,” he says. “We have three hundred collective years between us. Wisdom, though—wisdom doesn’t lift the rocks. We do.” Magee entreats us to go see the work; his helpers will open the great doors of each building. He often performs the titles of these pieces for visitors, but not today, he says. Go see.

The act of experiencing the Hill is an exercise in expansion and compression, of understanding something and then having that understanding upended. When the double doors of each building are thrown open, you can see to, and through, the opposite building. It takes time for a visitor’s eyes to adjust when moving from the bright sunlight into these spaces. The sculptures within have neat borders that frame a visual cacophony of movement, color, and texture. Most stand on a base or a set of stairs; one takes up most of the floor.

These are heavy-looking, heavy-feeling steel pieces that reveal a multitude of muted hues: blood-red, rusty orange, glass-green, muddy brown. Some of them are simple in form—one large square divided into nine sections. Others are quite complicated, involving elements that spin or door-like panels that open to reveal more works within the work. Magee layers splintered glass, glue, shellac, car parts, paprika, and animal hides into a rough landscape for spokes and grids, parades of rivets, or pools of glass. There are mazelike runs of steel arms that almost reach one another but end abruptly. There are small fields of ball bearings or burnt dirt, toothy skulls, corroded metal, rust, and grommets. There are openings that seem like cracked earth or the opening of a body cavity. Various touchstones spring to mind: one sequence of metal squares looks like musical notes along an unfamiliar staff; another construction looks like a diorama for some blasted city or the embodiment of a weighty train of thought that has been somehow disrupted.

The walkways among the buildings are important, for the simple brilliance of the rocks and sky outside provides a moment’s reprieve to process the contained wildness inside. And then it’s into the next building for the next series of puzzlements and thoughts. Outside, you get it; inside, you don’t, or not quite. The Hill is as confusing and moving as anything, or anyone, worth thinking about can be. “It’s an experience of architecture, space, nature, sculpture, painting, performance, and music in a remoteness that means you’re in effect making a pilgrimage to it,” Brettell said. “You’re moving, looking, going in and out of spaces. You become a part of a performance, and that performance is experiencing the work.”

The ride back to El Paso is quieter. The concrete city and its Pez-colored houses overtake the grass and ocotillo. Magee waves a lank hand at the stop-start rush hour traffic. “What we’re lacking in this world is quietude and intimacy,” he says. “That’s what the Hill tries to provide.” The winter’s light fades, and we part in the gloaming.

The next morning Michael and I sit in Livermore’s chapel, the wine-colored, barrel-vaulted installation off a busy corridor of El Paso’s University Medical Center. A mural of the cosmos stretches overhead, where a bird flies toward a rising sun whose fingers of light illuminate the clouds and streak toward the deep starry sky to the west. Framed poems line the walls, along with a series of Livermore’s watercolors of flowers. Each of these paintings hinges to reveal a receptacle into which visitors stash notes they’ve written. These notes are heartbreaking in their sweetness, written for an audience of God and strangers. “Gracias Sr. Jesus por otro día más,” reads the one in my hands. And “Trust in God.” If Magee created the Hill as a place for intimacy and quietude, Livermore’s done the same with the chapel. What a gift it is to offer a little peace in the maelstrom—to create a space that acknowledges the reaches of boundless hope and love. How tender a gesture.

Despite the umbra of Christianity that surrounds much of the work associated with Magee, he’s not conventionally Christian. He is, however, along with Livermore and Mayfield, ardent about the particular spirituality that informs their lives and work. “I believe in the great light,” he’d told me. “This world is beyond our comprehension.”

And at the Hill there is the wonder of ambition and achievement of the human will. Beyond those buildings and their artwork is the immense marvel of the sky, the desert, the timelessness and unwitting beauty of a world created not at all by people. “When the Bible says, ‘My thoughts are not your thoughts, nor are your ways my ways,’ it’s because we’re hardly evolved,” he says, invoking the Book of Isaiah. “We’re small. We’re just trying to make sense of it.”

The rocks and dirt and sun will remain a long, long while. The Hill will be there as long as it will be. The monk said to look at God’s handiwork. Glory, glory, hallelujah. Holy, holy, holy.

This article originally appeared in the October 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Big Things in the Desert.” Subscribe today.