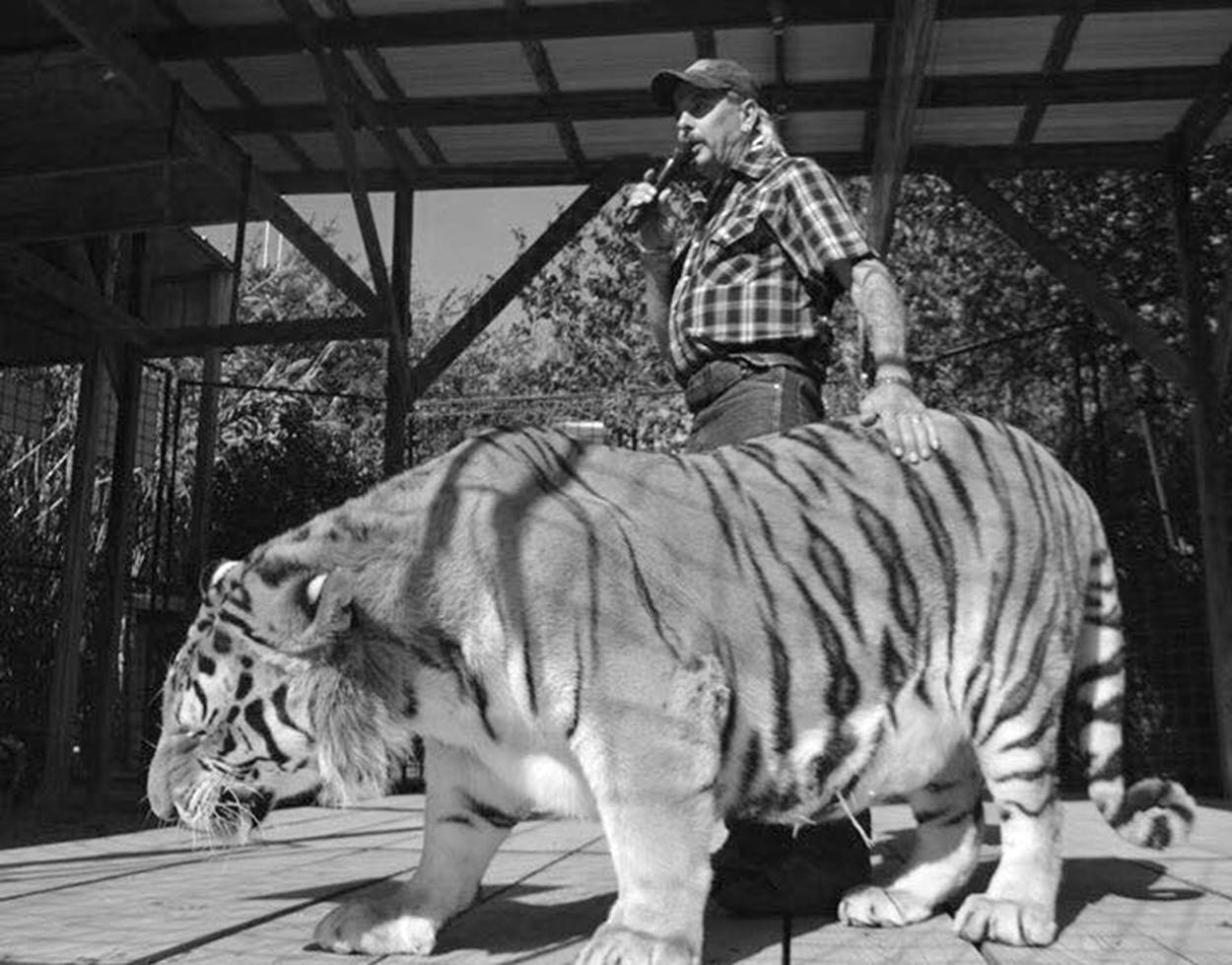

Joe Exotic was done. For the previous two decades, 55-year-old Joe had been the heart, soul, and ubiquitous public face of a massive private zoo in Wynnewood, Oklahoma, an hour north of the Texas line. He had boasted of owning the largest tiger collection in America. His sixteen-acre park was lined with metal cages, each filled with majestic tigers, lions, bears, alligators, and even tiger-lion hybrids called tiligers.

His sun-leathered visage, horseshoe mustache, and blond mullet adorned signs all over the zoo and all along I-35 between Dallas and Oklahoma City. His image covered the side of a tour bus as well as packages of condoms for sale in the zoo’s eclectic gift shop. His face had been on CNN, BBC, and CBS This Morning, and he had drawn millions of views on his YouTube channels and website, which hosted his shows, Joe Exotic TV and Joe Gone Wild.

Most of Joe’s life—many of his best moments and many of his worst—could be traced back to that zoo. He had for years both worked and lived on the property. But by August 2018, his kingdom had all but turned to dust. The zoo’s new owner, a flashy exotic animal breeder named Jeff Lowe, had squeezed Joe out of the business two months earlier and was in the process of dismantling much of the zoo, piece by piece, before taking its animals to another facility.

Joe had his issues with Lowe, but he blamed his troubles mostly on someone else: Carole Baskin, the owner of a big-cat sanctuary in Tampa, Florida. To those outside the exotic animal industry, Baskin and Joe appeared to operate similar facilities. But their philosophies diverged sharply on nearly every animal rights issue, notably the ethics of breeding big cats and allowing visitors to pet cubs, both of which had been fundamental parts of Joe’s business. Today there are more tigers in captivity than in the wild, and breeding remains a major point of contention between conservationists and private zoo owners like Joe. Baskin was Joe’s most vocal and effective critic, and in 2013 she had won a $1 million civil suit against him. He became consumed with revenge and repeatedly vowed to bring Baskin down.

But he had failed to do so, after years of trying, and lost everything in the process. Now all he wanted was to shed his identity and leave behind the swollen persona that had become the most recognizable—and controversial—the exotic animal industry had ever seen. So, along with his then 22-year-old husband and four dogs, he had split for Florida. They ended up at a Motel 6 in Pensacola, and soon discovered a bedroom community named Gulf Breeze. The sand was white, the water clear. He found work washing dishes at Peg Leg Pete’s, a pirate-themed seafood joint, and bartending for a catering company at night. He had found his new home.

On the morning of September 7, 2018, 81 days after Joe had left the zoo, he went to a local hospital to apply for a third job. It was a sunny Florida day—there was dew on the grass; the temperature was just right. Joe parked near the hospital and stepped down from his blue Ford F-150 with his résumé in hand. Suddenly, four unmarked cars skidded to a stop around him. In a flash he was surrounded by plainclothes law enforcement officers. Joe watched as they pointed their weapons at him and shouted, “Get on the ground! Get on the ground!”

He dropped and felt a knee drive into his back. He was cuffed and taken to the federal courthouse for an arraignment hearing. Joe learned that he was being accused of attempting to hire two hit men to kill Carole Baskin.

Suddenly he was famous again, his mulleted mug all over the national news. The story of how it had come to this would strain even the darkest imagination.

Before he was Joe Exotic, he was Joe Schreibvogel, born on a farm in rural Kansas. Though his parents had come from wealthy farming families, they did not pamper their children, and Joe always felt that he and his four siblings were born to work as farmhands. It was not an affectionate household. Joe’s parents rarely, if ever, told him they loved him.

His father, a Korean War vet, moved the family from Kansas when Joe was fourteen. First they went to Wyoming, where the property they owned seemed to Joe like an entire mountainside. Then they moved to Pilot Point, Texas, north of Dallas, where they lived in an eight-bedroom house on a large ranch.

Joe was not close with his siblings, except for his older brother, Garold. Joe and Garold shared a deep love of animals. Joe participated in Future Farmers of America and often brought home raccoons, ferrets, and other creatures to care for. He and Garold liked to watch nature shows on TV, and Garold confided in Joe that he hoped one day to live in the wild in Africa so he could see the beautiful beasts there running free.

When Joe graduated from high school, in 1982, he became a police officer in nearby Eastvale. At age nineteen, he was promoted to chief of police. It was a small department. Only a few officers worked under him, and serious crimes were rare.

Joe felt accepted by his colleagues, but he was only beginning to come to terms with his sexuality. Joe hadn’t yet told his parents that he was gay when one of his siblings outed him to his father, who made Joe shake his hand and promise not to attend his funeral. Joe was devastated. One day not long after, he was approaching a bridge in his police cruiser and decided he wanted to die. He veered into a concrete barrier, nearly plummeting over the edge of the bridge. He survived, but he was severely injured. He moved to West Palm Beach, Florida, and underwent months of difficult physical therapy.

There, he lived with a boyfriend and got a job working at a pet store. His neighbor worked at an exotic animal park nearby and would often come home with baby lions and monkeys that he’d let Joe bottle-feed. Joe was hooked. He moved back to Texas and began his career in the exotic animal industry.

In 1986 Joe, Garold, and Joe’s first husband—Brian Rhyne, whom he’d met at a bar in Dallas and married in an unofficial ceremony—bought a pet store together in Arlington. For the first few years they sold reptiles, birds, and small fish. Joe and Garold were both clever about finding ways to make money. Garold would dumpster dive behind furniture and carpet stores and turn the trash into cat playgrounds and doghouses, which he would sell. They used the money to expand their store, buying bigger cages for small exotic pets, like three-banded armadillos and four-eyed opossums. It was a nice little business that suited the brothers’ passions. But then, in October 1997, disaster struck. Garold was hit by a drunk driver outside Dallas. He died within a week.

Two of the darkest moments in Joe’s life—his attempted suicide and the death of his brother—had happened in Texas. Joe needed a change. The pet store was not the same without Garold, so Joe decided to sell it. He never forgot his brother’s love of wild animals, though, and with the help of $140,000 his family had won in a lawsuit related to Garold’s death, he bought sixteen acres of land about an hour south of Oklahoma City. Joe poured cement for sidewalks and built a row of nine cages. The Garold Wayne Exotic Animal Memorial Park opened two years to the day after Garold’s death.

Word spread quickly that Joe had opened an animal sanctuary, and people began dropping off exotic animals that they no longer wanted. Two of Garold’s pets, a deer and a buffalo, were the zoo’s first inhabitants. Then came a mountain lion. Then a bear. In 2000 Joe got a call from a game warden telling him that someone had abandoned two tigers in a backyard near Ardmore. Joe brought them back to the animal park. They were his very first tigers. He named them Tess and Tickles. They bred, and Joe raised their cubs. The beautiful beasts were hardly running free, but here they were up close. Garold would have loved it, Joe thought.

Trouble started early. In 1999, when the park was still under construction, Joe agreed to transport a flock of emaciated emus that had been rescued from a large pen in Red Oak, just south of Dallas. Some of the emus escaped while he was loading them up and headed for the freeway. Joe shot at least six of them, and they flailed around like chickens that had just been beheaded before they died. Local law enforcement and the SPCA blasted Joe for his recklessness, but a grand jury declined to indict him on animal cruelty charges.

Tragedy struck again in December 2001, when Rhyne passed away from a deadly infection. His funeral was held at the zoo. Within a year, Joe had a new lover and life partner, a 24-year-old named J. C. Hartpence. Aided by Hartpence’s experience as an event producer, Joe developed a traveling animal and magic show where kids could pet tiger cubs while learning about conservation. He used stage names like “Aarron Alex,” “Cody Ryan,” and “Joe Exotic,” performing in malls and at fairs across Texas and Oklahoma and as far north as Green Bay, Wisconsin, where a newspaper ad described him as “Master Illusionist Joe Exotic.”

Soon Joe needed more employees to help run the zoo and the road show. In the summer of 2003, he hired a nineteen-year-old named John Finlay. He moved in with Joe, and within a month they were in a relationship.

By this point, Joe’s relationship with Hartpence was already breaking apart. Hartpence was addicted to drugs and alcohol and had become disillusioned with Joe’s intentions for the zoo. Hartpence wanted to see it become a rehab-and-release sanctuary, with large enclosures where the animals had room to roam. Joe, on the other hand, was increasingly buying new animals from breeders and breeding animals of his own for profit. In mid-2003, Hartpence walked into the office and found a piece of paper on his desk. It was a printed color photograph of the zoo’s largest tiger, Goliath, menacingly baring his teeth over a big slab of meat. “J. C.’s remains” was typed in white letters over the picture. Attached was a Post-it note that read: “If you don’t get your shit together, this is gonna be your reality.” Hartpence recognized the handwriting as Joe’s.

One night, Hartpence waited until Joe fell asleep, then pointed a loaded .45 and a .357 Magnum at his partner’s head. Joe woke up to the click of the guns cocking. “I want out,” Hartpence told him. “Are we clear?” Joe talked Hartpence into putting down his guns, then he called the police. Hartpence was arrested at the zoo and never returned.

As Joe’s zoo grew and his traveling show booked more events, he began to attract more scrutiny from animal rights groups and federal regulators. In July 2004, the Oklahoman published an article about a crippled lion cub named Angel that had been born at the zoo, a possible result of inbreeding. “No legitimate animal sanctuary would allow that to happen,” said one activist quoted in the piece. It was Carole Baskin.

In 2006 the U. S. Department of Agriculture suspended Joe’s license for two weeks and fined him $25,000 for a long list of violations, including failing to provide adequate veterinary care and failing to remove feces from animal enclosures. Later that year, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals published a video showing what they alleged was mistreatment of the animals at Joe’s zoo and the animals that he used in the road show. PETA’s footage showed employees discussing irregular feeding schedules, swatting animals, and, in one case, striking a tiger with the butt of a rifle. The organization criticized the zoo for allegedly “churning out litters of tigers, lions, bears, and other exotic animals,” claiming that “some are deformed, likely because of inbreeding or inadequate nutrition for the mother during pregnancy.” Local and federal investigators arrived at the zoo to investigate the allegations, but ultimately no charges were filed.

By then the little 16-acre zoo had ballooned to hold more than one thousand animals (for comparison, the Dallas Zoo sits on 106 acres). There were more than a hundred tigers, plus lions, chimpanzees, leopards, baboons, alligators, and smaller reptiles. In 2001 the zoo reported total revenue of $117,022. By 2006 that number had grown to $539,320, the vast majority from donations. Alongside the growth of his nonprofit zoo, Joe expanded his for-profit ventures. In the zoo’s gift shop, he sold Joe Exotic–branded skin care products, alcohol, and condoms. Later, he opened a bar two miles down the road from the zoo called Safari Bar and then a pizza joint named Zooters. He was building a brand.

More than a thousand miles from Joe’s zoo, in Tampa, Florida, animal rights activist Carole Baskin was increasingly paying attention to Joe’s exploits. Baskin was born at Lackland Air Force Base, in San Antonio. Raised in Florida, she had hoped to be a veterinarian someday. In 1991 she married Don Lewis, a wealthy real estate investor. The next year, Lewis bought her a bobcat named Windsong. Baskin and her husband had saved it from an animal auction, where one bidder told Baskin he planned to club the cat over the head and stuff it. Baskin and her husband quickly realized Windsong needed a playmate or else she would tear apart their home. They found a man in Minnesota who agreed to sell them a second bobcat. Baskin was horrified when they arrived and discovered a metal shed full of bobcats being bred and slaughtered for their fur. She and Lewis bought every cat they could take back with them, 56 in all.

Baskin and Lewis continued to buy exotic cats that were destined for death at the hands of fur traders—28 more in 1994, 22 in 1995. They acquired forty acres of land and built Big Cat Rescue, a sanctuary that, much like Joe’s zoo, continued to grow as people who owned big cats became disenchanted with the animals they had bought. As Baskin’s reputation grew, she became inundated with calls and emails from people asking if certain sanctuaries were legitimate or not and wondering where they should donate their animals. She eventually started a website where she compiled detailed reports on private zoos and sanctuaries. She called it 911AnimalAbuse.com. Its tagline: “Find out who the bad guys really are.”

Baskin had a controversial background of her own. Lewis, her husband, disappeared in 1997 and was never found. Baskin was not a suspect in Lewis’s disappearance, but she was accused in the media by Lewis’s children, amid a dispute over his estate. An article in People suggested she might have fed Lewis’s remains to the tigers—an unfounded theory that would repeatedly be propagated by Baskin’s growing list of enemies.

Many exotic animal owners and private zoo operators despised Baskin for tracking their USDA violations and alleged mistreatment of animals. She frequently faced retaliation. She once opened her mailbox to find it teeming with snakes. On another occasion, after a tense Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission hearing about feral cats, she was physically attacked in the parking lot.

Nevertheless, she regularly searched for online news articles about traveling exotic animal acts and private roadside zoos like Joe’s and would write in the comment sections about why she believed what they were doing—breeding animals so that people could pay to pet the cubs—was wrong. In 2010 she realized she was often reading about the same traveling act—Joe Exotic’s, under his various stage names. She mobilized her growing list of followers to email the malls Joe had booked, to warn them about what she believed was his unethical behavior.

Then she began to receive concerning phone calls and emails. People were asking her why her sanctuary was sponsoring traveling road shows that allowed cub petting—something it didn’t do. Baskin soon realized what was happening: Joe had begun using the Big Cat Rescue name and logo to advertise his shows. In January 2011 she sued him in federal court for trademark infringement.

“If you think for one minute I was nuts before, I am the most dangerous exotic animal owner on this planet right now.”

As the court battle dragged on that year, Joe—who had begun to refer to himself as the Tiger King—started posting frequent tirades about Baskin online. Joe had built a television studio at his zoo and had been regularly broadcasting episodes of Joe Exotic TV on a website he created. On Christmas Day in 2011, Joe left a comment beneath an article about the zoo by a local news station in Oklahoma: “Dear Carole Baskin,” he began, “You should watch my show this tuesday as it is going to be about your back yard zoo, [and] why you have not found your husbands body . . . The next time you step foot in my business, you better run and hide real far and fast, and this is a promise to you for Christmas. You want to take this BS to the next level, lets play. See if your up to it . . . You dont know just how crazy I can be.”

Travis Maldonado arrived at Joe’s zoo in December 2013. He had struggled with meth addiction back home in California, and one of Joe’s employees suggested he take Maldonado in, thinking that working around animals would help him recover. Joe took a liking to Maldonado right away, and less than a month later, he, Maldonado, and Finlay were wedded in a three-way ceremony in a dance hall across the street from the zoo.

The ceremony was zoo-themed. The cake was orange with black tiger stripes, decorated with miniature chocolate cowboy boots and crocodiles made out of butterscotch. Some of the “flower girls” were monkeys. The ring bearer was a Celebes crested macaque. The three men wore pink button-down shirts and black pants. A candle near the altar was lit in memory of Garold.

The wedding was a high point in what otherwise turned out to be a tough year for Joe. For one thing, his relationship with Finlay soon began to fall apart. Finlay felt that Joe had become manipulative and controlling. And the park dominated their lives; they rarely left it for anything that wasn’t work-related. Joe had also become obsessed with his web TV episodes gaining more views, and he relied on increasingly wild stunts to drum up excitement. Finlay had seen enough and was ready to leave. It was a messy breakup. On August 18, 2014, Finlay attacked Joe in the back parking lot. He was arrested and charged with assault and battery.

Worse than losing another lover, Joe had lost the copyright infringement lawsuit filed by Baskin, and as a result he owed her $1 million. He filed for bankruptcy, dissolved the Garold Wayne Exotic Animal Foundation Memorial Park, which was registered under his name, and had his associates form a new entity, called the G. W. Interactive Zoological Foundation, which temporarily kept the park safe from Baskin’s collection efforts.

Meanwhile, Joe had become increasingly paranoid that animal rights groups were sending spies to the zoo. He repeatedly posted social media photos and videos of himself firing weapons and toying with explosives, warning animal rights activists, “Don’t fuck with me.”

He also frequently addressed Baskin from his TV studio at the zoo. “For Carole and all of her friends that are watching out there, if you think for one minute I was nuts before, I am the most dangerous exotic animal owner on this planet right now,” Joe had said in 2012. “And before you bring me down, it is my belief that you will stop breathing. Got that?”

During another episode, in February 2014, Joe brought out a blow-up doll with a blond wig, apparently a crude rendering of Baskin. “You wanna know why Carole Baskin better never, ever, ever see me face-to-face ever, ever, ever again?” Joe asked, before suddenly raising a pistol to the doll’s head and pulling the trigger. There was a loud bang, and the doll keeled over. “That is how sick and tired of this shit I am,” Joe said. “Have a great night, ladies and gentlemen, and I will see you tomorrow night.”

On March 26, 2015, the alligator compound at the zoo exploded in fire. All of the alligators but one were boiled alive. Also lost in the blaze, according to Joe, was his TV studio. Local investigators speculated that the fire was the result of arson. No one was ever arrested, but Joe claimed animal rights activists “targeted the studio to shut me up.”

By then, Joe had been moving toward a settlement that would have ended Baskin’s continuing litigation to collect the $1 million judgment. After a ten-hour-long mediation hearing in downtown Oklahoma City, the parties reached an agreement: Joe would pay modest monthly payments toward the $1 million judgment. He would keep the zoo but could no longer offer cub petting and would stop breeding big cats. Baskin’s lawyers sent a draft of the agreement to Joe’s attorneys, thinking their legal saga was nearly over.

Days went by, and they heard no response from Joe or his attorneys. The mediator set up a conference call with Joe and his legal team on November 12, 2015, to see what was holding things up. An unfamiliar voice came over the line: “There is no deal. We’re not doing this deal.” Someone asked who was speaking. “Jeff Lowe,” the voice said.

Joe first met Lowe around June 2015, when Lowe stopped by the zoo to buy a baby tiliger cub. Joe had marveled as Lowe pulled up in a Hummer towing a trailer that had once been owned by Evel Knievel; Lowe had once managed Evel’s son Robbie. He paid $7,500 cash for the tiliger and told Joe that he planned to open a sanctuary in Colorado. Lowe invited Joe and Maldonado to his house there in September of that year. (The law had changed and they’d legally wed; the trip was their honeymoon.) They went skydiving and hung around the pool. Joe was having health problems, and he had become increasingly worried about what would happen to the zoo if he died or could no longer manage it. According to Joe, Lowe offered to put the zoo in his name, to ensure it never went to Baskin.

Joe agreed, believing he had found a wealthy benefactor. Lowe had his own shady history, though. In 2007 he was sued by the musician Prince for allegedly selling clothes with Prince’s trademarked symbol on them. The next year, Lowe pleaded guilty to federal mail-fraud charges after he posed as an employee of a charity for domestic abuse victims to obtain $1 million worth of merchandise that he later resold.

Lowe moved to the zoo in Oklahoma and lived with Joe in the main house while waiting for his own residence to be built on the property. Within a few months, however, the relationship between the two men soured. Both men had strong personalities, and tensions were high now that they shared the same space and essentially co-owned the zoo. Meanwhile, Baskin’s continued attempts to collect on the $1 million judgment only agitated Joe more.

Around the same time, a former Dallas strip club owner named James Garretson started spending time around the zoo. He had decided he wanted to open an exotic animal–themed bed-and-breakfast, so he purchased several tigers. According to Garretson, Joe asked him if he knew any hit men. (Garretson figured Joe thought he was connected to the crime world because he sometimes brought around people with lots of tattoos.) Joe told him he wanted to have Baskin killed and said he could offer $10,000 for the job. Garretson dismissively told Joe that he’d look around, but he never did.

In February 2017, a new employee at the zoo, Ashley Webster, walked up to say hello to Joe and Lowe and overheard them talking about Baskin. Joe turned to Webster and asked if she’d travel to Florida and put a bullet in Baskin’s head for a few thousand dollars. Webster became uncomfortable, and she laughed it off to get out of the conversation. But she believed Joe was serious.

About two weeks later, Webster quit her job and left a voicemail for Baskin, warning her of Joe’s latest threats. “I just wanted to apologize to you because I have believed the bullshit that Joe Exotic has said,” Webster declared. “I am currently here at his place right now, and I’m leaving . . . He was actually talking about paying someone to kill you. He tried to get me to do it. I’m not going to fucking do that . . . He was offering, like, a couple of thousand dollars. I feel like your life is in danger.”

Baskin turned the voice mail over to her attorney, and it made its way to Special Agent Matthew Bryant with the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which had been investigating Joe and the zoo for potential wildlife crimes. Murder for hire was not a crime he typically saw. After hearing Webster’s voice mail, he met with FBI agent Andrew Fairbow and some federal prosecutors.

In late August, Garretson stopped by Joe’s office, where Lowe pulled up a map on a computer that detailed Baskin’s property in Tampa. “He started showing me easy ways to kill her,” Garretson said later. Lowe noted Baskin’s favored bike paths, pointed out the location of the gift shop at her sanctuary, and showed images of her house, which sat isolated at the edge of an inlet. Joe then came in and placed a thick manila folder on the desk. He said it contained detailed information on Baskin.

It’s unclear whether Lowe was seriously plotting to end Baskin’s life. If he was, Garretson learned, he was also working other angles. Later that same month, according to Garretson, Lowe suggested he call Baskin behind Joe’s back and ask if she wanted to purchase the zoo. Lowe said that if the zoo sold, he’d give Garretson $100,000. He told Garretson to let Baskin know that all of Joe’s files and computers would be included in the sale. Lowe told Garretson he was offering Joe up to Baskin on a silver platter.

Garretson never heard back from Baskin. But he did receive a phone call from Bryant, the USFWS agent. They set up a meeting for September. By this point, Garretson had come to dislike Joe. He believed Joe had been mistreating the animals, and he had become unnerved by the constant threats against Baskin and drama at the zoo.

Joe selected five aging tigers and killed them one by one, firing a shotgun into their skulls.

When Bryant asked Garretson to be a confidential informant, he agreed. Bryant showed Garretson how to work a concealed recording device so he could capture his conversations on video, and an audio recorder so he could tape phone calls.

Bryant had a plan to set Joe up with an undercover agent posing as a hit man. If Garretson could convince Joe to hire the undercover agent, they would gain control over the situation, rather than having to discover and try to stop any plot that Joe may have been working on in secret.

On September 29, 2017, Garretson recorded his first conversation with Joe since signing on as a confidential informant. He met Joe outside his office at the zoo.

“When is she ever gonna fucking stop?” Garretson said, referring to Baskin.

“She won’t until somebody shoots her,” Joe replied. “Her day is coming, man.”

On October 6, 2017, Joe’s phone rang with news of another disaster at the zoo. His husband, Travis Maldonado, was dead. “My entire soul died,” Joe said later.

According to Joe, Maldonado had been joking around with the staff of the zoo’s gift shop. He was showing off his Ruger pistol. In an effort to prove something he thought he had read on the internet, he took the magazine out of the gun and, knowing there was a bullet in the chamber, held it up to his head, believing that if he pulled the trigger it would not fire. He was wrong. Maldonado died before the first responders arrived. He was 23 years old.

Local news reporters descended on the park, and Joe held a press conference at the zoo the next day. Standing in front of a backdrop covered in Joe Exotic TV logos, he wore a pink button-down shirt, similar to the one he wore on the day he and Maldonado were married. He was inconsolable as he explained that the shooting was accidental, not a suicide.

Late one night, not long after Maldonado’s death, John Finlay got a phone call from Joe. Finlay, the estranged third member of Joe’s three-way union, had come back into Joe’s orbit eventually and now managed the Safari Bar. He couldn’t understand what Joe was saying, but he could hear that Joe was crying uncontrollably. Finlay drove over to Joe’s house. He searched the living room, the kitchen, and two bedrooms but found no sign of Joe. Finlay finally discovered Joe sitting in the converted garage. He was sobbing, and he held a cellphone in one hand and a gun in the other. He had shot at a television screen nearby.

After that, Joe began to lose his drive to run the zoo. The man he had believed to be his fiscal savior, Jeff Lowe, had turned out to be a far more combative associate than he had expected, and the zoo had fallen into a state of constant crisis. It was hard for Joe to find peace. He would often walk the grounds in the early morning, gazing up into the clouds, hoping to see Maldonado’s face. Then he’d look around and see the rows of cages filled with tigers. Joe came to believe that the zoo no longer represented what he’d wanted it to be when he first opened it in his brother’s memory. “I have all these animals on display, suffering, so I can suck donations out of people,” he later testified.

One evening in October 2017, Joe was expecting a shipment of animals from a circus manager who had been paying Joe to board his cats in the off-season. According to Erik Cowie, a longtime zoo employee, Joe needed to make cage space for the incoming animals. There were some new employees on hand, and Joe told Cowie to lead them away from the tiger cages. Joe then selected five aging tigers and killed them one by one, firing a shotgun into their skulls.

Cowie had been in charge of caring for the tigers—Samson, Delilah, Lauren, Trinity, and Cuddles—and he thought they were perfectly healthy. Once the gunshots ended, Joe emerged from the tiger cages. “Jesus,” he said, “if I knew it was this easy, I’d just blast them all.”

If Joe was beginning to let go of the zoo and its animals, he wasn’t yet letting go of his war with Carole Baskin. One of the zoo’s new employees at the time was a maintenance man named Allen Glover who had worked for Lowe before. A sixth grade dropout with a long list of felony convictions, he had a teardrop tattoo under his eye that he got while serving time in Louisiana. According to Glover, one night at around 11 p.m., he had just gotten off of work and was returning to his trailer on the property, when he found Joe on the front porch of the gift shop. Glover had often heard Joe talk about Baskin, and now his new boss was asking him to kill her. Glover figured his tattoo—sometimes interpreted as a symbol of having killed before—gave Joe the idea. According to Glover, Joe offered $5,000 up front for the job. Glover said yes. Joe strategized about how it should be done, suggesting Glover use a crossbow or a long-range rifle and target her while she took one of her long walks on the trail outside her house.

When Garretson caught wind of the plot, he wasn’t sure what to make of it. He called Lowe to get some more information about Glover and again recorded the conversation. “He’s serious, but I don’t think he’s capable without fucking it up,” Lowe told Garretson. “He’s reckless. He’s careless . . . This whole fucking crew is like a clown assassin.”

That same day, Garretson recorded a phone call with Joe. They discussed the Glover plot. “As long as we don’t get caught red-handed, we got this,” Joe told Garretson. “But if they bust him red-handed, me and Jeff got our story down to where we fired him and he just went off the deep end.”

According to Glover, one day in mid-November Joe handed him an envelope stuffed with cash. Glover went back to his trailer to count it. It was $3,000, not the $5,000 they had agreed on, but Glover didn’t care. He didn’t trust Joe, and he just wanted to leave.

The plan, as far as Garretson knew, had been for Glover to buy a bus ticket, travel to Tampa, and kill Baskin. Garretson had relayed that information to Bryant. They planned to stake out the zoo and several local bus stations on the day Glover had said he was going to leave. When Glover got on the bus, they’d arrest him and Joe.

But Glover had a bad back, and he wasn’t about to travel across the country by bus. When he departed from the airport in Oklahoma City on November 25, 2017, bound for South Carolina, Garretson and the feds were out of the loop.

Without knowing Glover’s whereabouts, agents Bryant and Fairbow decided to call Baskin and warn her. They informed her there was an “imminent threat,” but they couldn’t tell her much more. Baskin began to take precautions. She installed blinds in her house so potential snipers couldn’t see inside. She installed security cameras on the property. She used to ride her bike to work every day along the trail. Now she avoided it.

She worried her mailbox could be rigged with explosives. She steered clear of vans entirely, afraid she might be kidnapped. If she walked out of the grocery store and saw someone had parked next to her, she went back inside and waited until the car left. She began carrying a gun, and she kept it by her bedside every night. No place felt safe. One night Baskin heard what sounded like someone tearing through the screen on her back porch. There’s somebody here to kill me, she thought. It turned out to be neighborhood dogs. Weeks passed without incident. Joe, meanwhile, hadn’t heard from Glover.

Glover later testified that he never even made it to Tampa. He said he had no intention to kill Baskin and only wanted to rip Joe off. After arriving in South Carolina, however, he figured he should probably warn Baskin—in person. He drove down to Florida. He was drunk and high the entire way. He pulled off somewhere, blew a bunch of the money Joe gave him partying on the beach, woke up the next morning in an unfamiliar hotel room, and drove back to South Carolina. He never contacted Baskin.

It became clear to Joe that Glover was not going to carry out the hit, and Garretson finally arranged a meeting between Joe and the undercover agent posing as a hit man.

The fake hit man, “Mark,” arrived at the zoo on December 8, 2017. Garretson recorded their conversation. Joe explained that he needed time to raise enough money. It was the winter season, and attendance was typically low, but he was waiting on a litter of cubs. He offered Mark $10,000 total, $5,000 of it up front. “That bitch has just got to go away,” he said. “Just follow her into a mall parking lot, cap her, and drive off.”

Joe didn’t have the money to pay Mark yet, and no money exchanged hands. Garretson tried to set up another meeting, hoping to capture Joe exchanging money with Mark, but Joe was preoccupied. Three days after the meeting with Mark, Joe was getting married again, this time to Dillon Passage, a young man from Austin. Over the next few months, Garretson recorded several more conversations with Joe, but Joe repeatedly said that he had not yet come up with the money.

Then, in April, Jeff Lowe returned to the zoo after spending some time in Las Vegas. He and Joe quickly had a falling-out. Joe stopped talking to Garretson too. By summer, everything had come to a head for Joe: the legal battering by Baskin, his contentious business partnership with Lowe, the death of Maldonado, and his failing faith in the mission of his own zoo. Then an employee alerted him to a physical altercation between Lowe and Dillon in the parking lot. That was the last straw.

One day in June, he packed up everything he could fit into a trailer, left the zoo, and rented a house with Dillon in nearby Yukon, Oklahoma. Everywhere he went in search of a job, people recognized him as Joe Exotic. He couldn’t buy gas, and he couldn’t even go to Walmart without people hounding him for selfies and autographs. It was hardly a clean break. He asked Dillon where he would want to live if they could go anywhere. Dillon said he wanted to live on the beach. So in August they packed up again and this time left for Florida.

Joe Exotic arrived in the courtroom at the federal courthouse in downtown Oklahoma City for the first day of his trial in March 2019 wearing a gray suit with a tie and dress shoes. It was odd to see him dressed like that—he typically wore a flashy button-down shirt and a baseball cap or a fringed jacket. He still had his blond mullet.

He stood accused of attempted murder for hire and of violating federal regulations that protected exotic animals. Erik Cowie testified on the first day of the trial. He told the jury about the five tigers that Joe had killed. He talked briefly about caring for Cuddles, who he called “a clown.” He said he watched as a new tiger filled Cuddles’ s empty cage. Prosecutors showed photos of tiger carcasses that federal agents dug up in the back of the zoo. One Fish and Wildlife Service agent testified that they were stuffed in their graves like “hot dogs in a pack.” It was a devastating beginning to Joe’s trial.

Baskin sat in the back row. She was still afraid for her life; federal agents escorted her between her hotel and the courthouse. She testified as the prosecutors exhibited dozens of Joe’s graphic threats. She was composed on the stand and pointed out that what had been shown in court was just a “very, very small sampling” of what he had said about her over the years. “I believe he blames me for everything that goes wrong in his life.”

The prosecutors called a string of Joe’s former compatriots from the exotic animal industry, who testified that they had bought and sold exotic animals in transactions with Joe, often by fudging USDA paperwork. James Garretson testified, and his recorded conversations with Joe were played in court. The jury repeatedly heard Joe say that he wanted Baskin dead. “Just roll that fat bitch into the ocean,” Joe said on one of those recordings.

When Allen Glover, the would-be hit man who ran off with the money, took the stand, he was gruff and rude and easily confused. He explained that he wanted all along to take Joe’s money and run. He said he let Joe believe his teardrop tattoo meant he had killed before, when really it was meant to memorialize his late grandmother. “To get that money from Joe, I’d let him believe anything he wanted,” Glover said.

Joe took the stand on the trial’s sixth day. He gave rambling testimony, claiming he’d been set up by Jeff Lowe, who wanted to kick him out of the zoo behind his back. He accused Lowe, Garretson, and Glover of conspiring against him and of running various criminal schemes from the zoo. He said Lowe told him to give Glover $3,000 so that Glover could travel to South Carolina, and that he did it because he thought it would get Glover out of his hair.

Joe admitted to shooting the five tigers. He said it was because they were old and in poor health. Euthanasia by gunshot, he noted, is legal. “In twenty years I’ve had fifty plus tigers buried in that back pasture, and nobody gives a damn. Nobody.”

When confronted with his own recorded statements—the many threats against Baskin, his discussions about the Glover murder plot, and his discussions with the undercover hit man—he said he knew that Lowe and Garretson had been up to something and that he was playing along only to gather evidence. He accused Lowe of everything from drug use to sex trafficking. Lowe’s name was mentioned repeatedly during the trial, but he was never called to testify. Lowe declined to comment for this story, claiming he had sold his exclusive life rights to Netflix. (He hadn’t.)

In her closing statements, the lead prosecutor, Amanda Green, urged the jury not to believe Joe’s story. “The Tiger King: that’s how [Joe] has marketed himself and lived his life,” she said. “But here’s the thing with kings—they start to believe they’re above the law.” The jury wasn’t swayed by Joe, and on April 2 he was convicted on all counts. He may go to prison for twenty years. He accepted the verdict silently, staring straight ahead into the distance.

Baskin wasn’t in the courtroom to see it. She left after three days of the trial. Back at her sanctuary, in Tampa, she was relieved when the verdict came in. We spoke a week after the trial, in the living room of a small ranch house at Big Cat Rescue, surrounded by wall art depicting exotic cats. She hoped that if Joe were handed a strict sentence, it might deter others in the exotic animal industry from operating zoos like his. Yet it troubled her that Joe, even from jail, had remained involved in the exotic animal business. In a recording that was played during the trial, he appeared to be brokering the sale of some lion cubs through Dillon.

I spoke to Joe’s ex John Finlay too, in late March. He was living in a Motel 6 off I-35 in Oklahoma. He’d found work as a welder, and he lay underneath the covers on his bed as he spoke to me. He had the name of his favorite tiger from the zoo, Ledoux, tattooed on his stomach. He told me Joe had ruined his life, but he was hopeful about having the chance to start over. “This is going to be the beginning of my life without him in it,” he said.

J. C. Hartpence, Joe’s second partner, was not so fortunate. He spoke to me after the trial by phone from the Larned Correctional Mental Health Facility, in Kansas. After he left the zoo, his life continued on a downward spiral. He was convicted in 2006 of molesting a child younger than fourteen, and he murdered a man in Kansas in 2014. He could spend the rest of his life in prison.

A week after the trial, I began talking to Joe on the phone from the Grady County Jail, where he was awaiting sentencing. At first he was reserved. He hardly resembled the bombastic man I had watched on the witness stand and in his many videos. He told me of his childhood, about his loveless family. He told me he was sexually abused when he was five. He spoke fondly of the early days of the zoo and seemed proud of the animals he had rescued.

I asked him if he regretted posting any of the things he had about Baskin. He said no, explaining that he had to act tough online in the face of hostile animal rights activists. He reiterated his claims that he was framed, and he questioned the motives of the prosecutors. “Am I in jail until they can shut down this industry, or am I taking the rap for all these other people?” His voice rose, and his tone grew darker. “Come hell or high water, at some point, I’m gonna make world news, okay? Something’s gonna change in the name of Joe Exotic.” I asked him what he meant. “This is a recorded telephone, so I’m not gonna tell you that,” Joe said. “But at some point, bet your ass, I’m gonna make world news.”

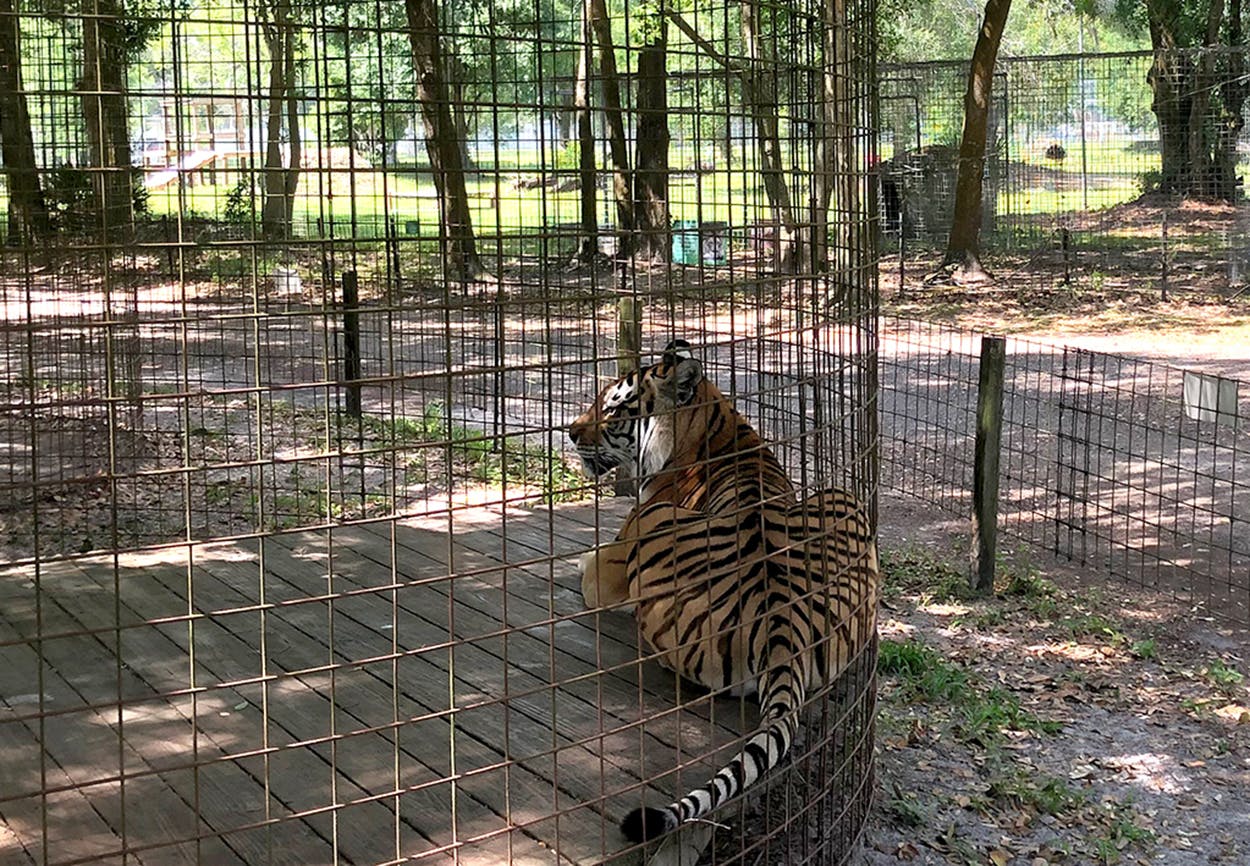

I visited the zoo the day after Joe was convicted. It was 11:30 in the morning on a Wednesday, and I was the only visitor there. Signs warned every few feet of surveillance cameras and armed guards. Many of the cages were empty, and the ones that weren’t held cats that paced aimlessly inside their small enclosures. There were piles of dried feces in some of the cages. It took me about twenty minutes to walk slowly through the zoo.

Tacked onto many of the enclosures were faded placards from donors, often memorializing the dead. “This compound is in loving memory of Grace Maples. We loved you best. Robbie, Tena and Cameron Wilson, Ft. Worth, TX,” read one. “This Tiger Complex was Built in Loving Memory of Jarrod ‘Willis’ Hurley,” read another. “May your spirit be free.”

It was a reminder of what the zoo could have been and of what Joe once supposedly wanted it to be: a living memorial, a sanctuary from the tragedies in life, both animal and human. One person not memorialized anywhere at the zoo was the Tiger King. Joe’s face had been scrubbed from the property. Even the billboards on I-35 had been taken down. Somewhere in the back pasture, there were more than fifty dead tigers. There was no memorial for them either.