He first began frequenting San Bernardo Avenue, in the border city of Laredo, in the late spring of 2018. He was in his mid-thirties, a strapping man, at least six feet tall and two hundred pounds. His black hair was neatly trimmed on top and shaved on the sides, like a military cut, and he had a stubble beard. He drove a white 2015 Dodge Ram 2500 pickup that always appeared to be freshly detailed.

He usually showed up after dark, slowing as he came to the four-block section of San Bernardo a couple of miles north of downtown that many Laredo residents called “the prostitute blocks,” an area dotted with fast-food restaurants, gas stations, convenience stores, and low-rent office buildings. On any given night, there were six to ten women working the blocks. Whenever the man would pull up beside one of the women in his pickup, he would give her a smile. He told some of the women his name was Juan; with others, he went by David. He sometimes asked for oral sex, never intercourse, and every now and then he’d just want to go for a drive and talk. Occasionally he would take a woman to his home in a well-kept subdivision in far north Laredo, explaining that his wife and children were out of town. After an hour or so, he would drive her back to San Bernardo, hand her some cash, and wish her, as she stepped out of his white Dodge, a good evening. One of the women would later tell a close family member that he was the most pleasant of all the men she met there.

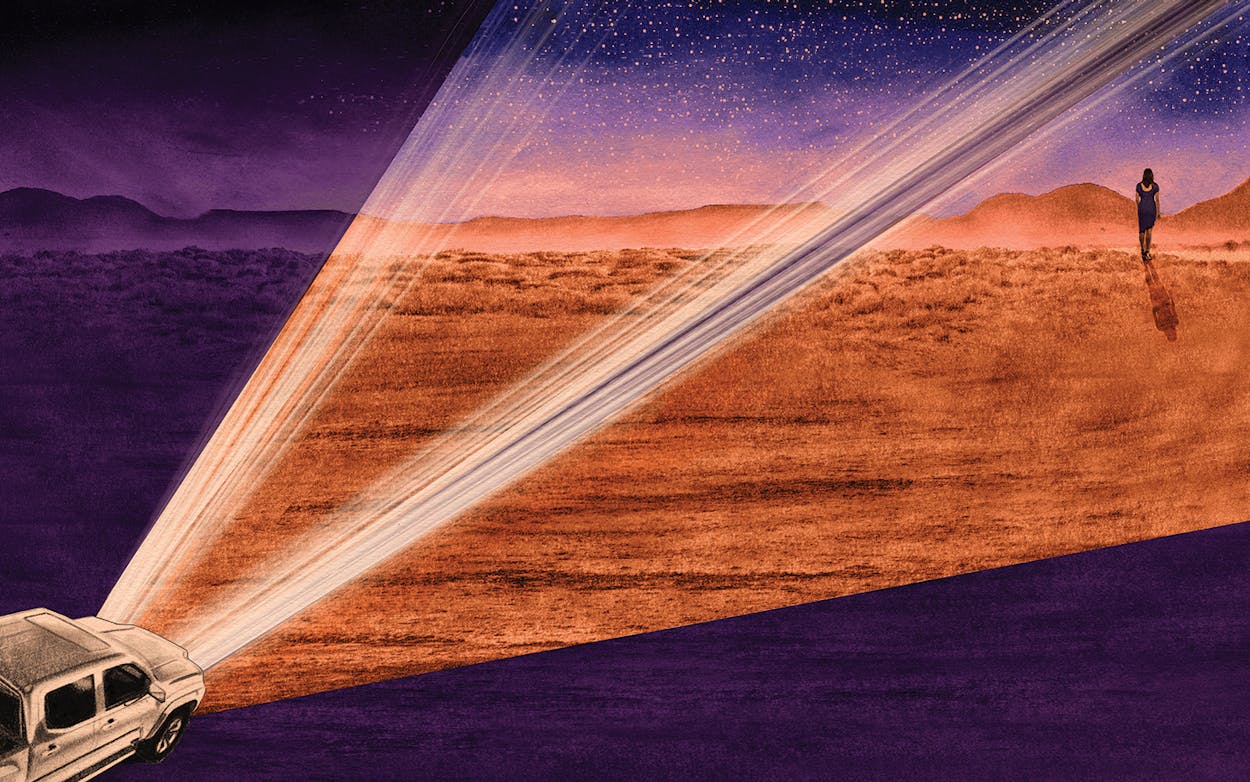

On September 2, 2018, the day before Labor Day, he arrived at the prostitute blocks in the late evening hours and spotted Melissa Ramirez, a 29-year-old with thick black hair. Ramirez had been working San Bernardo for nearly a decade. That night, she wore a light-colored tank top and black shorts. She hopped in the man’s truck, and they drove away.

At around noon the next day, the Webb County Sheriff’s Department dispatcher received a call from a rancher who had discovered a woman lying facedown on the side of a dirt road in a remote part of the county, 24 miles north of Laredo. A deputy was sent to investigate. The woman, who was clutching a bag of M&M’s, had been shot three times in the head and once in her right wrist. On the ground beside her were .40-caliber bullet casings, suggesting she had been gunned down at point-blank range. This was not just a murder. It was an execution.

The woman was transported to the county morgue, where she was identified through her fingerprints as Melissa Ramirez. A computer search showed that she had been arrested for prostitution on San Bernardo in 2008. Two Texas Rangers and two detectives from the sheriff’s department drove to Rio Bravo, a low-income border community thirteen miles south of Laredo, where Ramirez had lived in a green mobile home with her mother, Maria Cristina Benavides, and two of Ramirez’s children, a daughter and a son, ages seven and three. A small, wobbly trampoline, a pink dollhouse, and other toys were scattered across the yard. An American flag was mounted on the front of the mobile home. Benavides, a kind, slightly stooped woman, invited the officers into her trailer, and they informed her that her daughter had been murdered.

Ramirez was the third of Benavides’s four children; “mi niña hermosa” (“my beautiful girl”), Benavides liked to call her. Growing up in Rio Bravo, Ramirez learned to play Mexican folk music on a wheezy accordion, and she memorized the lyrics to Selena’s pop songs, always singing along when they played on the radio. Whenever the ice cream truck drove up and down Rio Bravo’s worn streets, she begged her mother for spare change so she could buy ice cream for her friends who had no money.

According to Benavides, Ramirez had been a good student. But when she was a teenager, she was sexually assaulted by an uncle of one of her friends, and her life began to spiral. She dropped out of high school, became addicted to Xanax and other prescription drugs, and eventually turned to cocaine. She later became a mother, and though she doted on her children, she continued to be plagued by addiction into her twenties. Sometimes, desperate for money to buy drugs, she would leave her kids with Benavides, catch the El Aguila Rural Transit bus from Rio Bravo to downtown Laredo, and walk up San Bernardo to the prostitute blocks. After a few days, Ramirez would return to the green trailer. Benavides would cook Ramirez’s favorite meal, picadillo. Ramirez would watch funny YouTube videos with the kids. Inevitably, though, she would return to the bus stop and head back to San Bernardo.

The investigators asked Benavides if Ramirez had ever mentioned anything about the men she’d met in Laredo. Did she ever have problems with one of them? Benavides shook her head. Ramirez sometimes came home with a busted lip or a bruise on her face, but she didn’t talk much about her life on San Bernardo, she said.

Benavides watched the investigators walk to their cars, and then she hurried across the street and collapsed into the arms of her neighbor, Alma Garza. She told Garza she had no money to pay for a funeral.

“And what am I going to say to the children?” Benavides asked. “What do I tell them about their mother?”

The Texas Rangers and the detectives assigned to the case headed to San Bernardo. But no one they spoke with had seen Ramirez get into a vehicle the night before Labor Day. Nor did anyone remember Ramirez telling them about an encounter with a client going bad in recent weeks.

Priscilla Villarreal, who’s become famous in Laredo for her bravado as a night-crawling citizen journalist, also searched for leads. Villarreal, who goes by the nickname Lagordiloca (roughly, “the Big Crazy Lady”), spends her evenings cruising the streets of Laredo in her pickup, which she calls the Blue Demon. Whenever she gets a tip about a crime in progress, an immigration raid, or anything else that interests her, she races to the scene, pulls out her cellphone, and livestreams the unfolding events, unedited, to her 130,000 Facebook followers.

Villarreal often patrols San Bernardo, and she’s close to many of the women who work there. Whenever she’d see Ramirez, she’d always ask how she was holding up. Ramirez would smile and simply say that she was getting by. Ramirez, Villarreal said, was such a sweet girl. She could not imagine why someone would take Ramirez to a rural part of the county, shoot her in the head three times while she was eating M&M’s, and then drive away.

“Por favor tenga cuidado,” Villarreal warned the women on San Bernardo. Please be careful. “Algo malo está pasando. Algo muy malo.” Something bad is happening. Something very bad.

It’s probably fair to say that most Texans have never been to Laredo, which is 157 miles south of San Antonio. The only thing many of them know about the city is that it’s the setting for the famous country and western ballad “The Streets of Laredo,’’ about a dying young cowboy making plans for his funeral. But Laredo is far from a cowboy town. With more than 260,000 residents, it’s the tenth-largest city in Texas and the third-most populated on the U.S.-Mexico border, behind San Diego and El Paso.

Laredo is home to a philharmonic orchestra; a semiprofessional soccer team; Texas A&M International University, which has an enrollment of 7,600 students; and 24 Catholic churches, all of which offer Spanish-language masses. Each winter, the city hosts a nationally renowned birdwatching festival, and it holds an annual Mardi Gras–like celebration of George Washington’s birthday, in which Laredo’s elite dress in colonial costumes and attend pageants, balls, and parades. Downtown is the historic tree-lined San Agustín Plaza, where residents have been gathering since the late 1700s, and near the plaza are rows upon rows of Mexican import shops, which attract shoppers in search of everything from quinceañera dresses to hand-painted furniture.

Laredo’s economy, of course, is fueled by the border: the city is the largest border crossing for goods traded between the United States and Mexico. (And it recently surpassed Los Angeles as the largest port in the entire country.) More than two million eighteen-wheelers roll across Laredo’s international bridges each year, carrying everything from automobile parts to squash. Certainly, much drug trafficking and human trafficking is routed through Laredo. Yet for all the talk among politicians about border crime, Laredo, like most border cities, is a reliably safe place to live, with lower crime rates than Dallas and Houston. Most of the area’s violent crime takes place in Nuevo Laredo, the cartel-controlled sister city on the Mexican side of the border. Since 2010, Laredo has rarely seen more than twelve murders a year, and those are almost always solved after routine investigations, with arrests coming quickly.

Unsurprisingly, the brutal slaying of Melissa Ramirez incited a lot of chatter in Laredo law enforcement circles. After a couple of days of investigation, the Rangers and Webb County sheriff’s detectives did make some headway, collecting the names of three men who were said to have associated with Ramirez. The investigators then visited the South Texas Border Intelligence Center, a two-story, seven-thousand-square-foot facility in north Laredo that’s run by the U.S. Border Patrol. It coordinates the efforts of every local, state, and federal agency in the region that is involved in border security.

The investigators knew that the Border Patrol had installed automated cameras throughout the web of rural roads outside Laredo in hopes of catching undocumented immigrants and drug mules. Although there were no cameras in the immediate area where Ramirez’s body was found, there were a few nearby. The Rangers and sheriff’s detectives asked the Border Patrol to run license plate checks on vehicles photographed on those roads over the Labor Day weekend. If a vehicle belonging to one of the three men who knew Ramirez had been photographed, the investigators would have a prime suspect.

One of the center’s intelligence supervisors, a 35-year-old agent named Juan David Ortiz, was asked to assist the investigation. He was filled in on Ramirez’s murder, and he and his team promptly ran license plate checks. They didn’t discover any connections to the three suspects, but they did identify a car that belonged to a police officer. When investigators interviewed him, the officer explained that he was looking at property in the area, and he was cleared.

The Rangers and sheriff’s detectives were back to square one. Ramirez’s killer, they realized, could be anyone: a young oil field worker, a drifter, a businessperson. A Mexican citizen, driving across the Gateway to the Americas International Bridge at night and then crossing back into Mexico before the sun rose. A wholesaler from another Texas city who came to Laredo to buy goods at the import shops. For ten days after Ramirez’s murder, investigators made little progress.

Then, on the morning of September 13, the body of a 42-year-old woman named Claudine Luera turned up on a dirt road less than two miles from where Ramirez’s corpse had been discovered. She was dressed in a pink sweater and blue jeans. She had been shot once in the head, and next to her body was a .40-caliber bullet casing.

Luera had grown up in a neighborhood near downtown and had attended Raymond & Tirza Martin High School, which happened to be located on San Bernardo, less than half a mile from the prostitute blocks. Growing up, she and her sisters were called las blanquitas (“the whiteys”), because they were biracial. (Their father was Hispanic, and their mother was Scottish.) After high school, Luera had worked for a time as a clerk for the district attorney’s office. But she eventually became addicted to heroin. In 2014, Child Protective Services took away her five children and placed them in the custody of Luera’s sister and aunt. By 2015 she was working on San Bernardo.

Like the other prostitutes, Luera had been unnerved by Ramirez’s murder. After Ramirez’s body was found, Luera took a cab to the apartment of her eldest child, who was in college studying to become a nurse. Luera said she was scared and wanted to leave her life as a prostitute. But the pull of heroin was too strong. Within a few days, Luera was back on San Bernardo, and a few days after that, she was dead.

The cops initially tried to keep Luera’s murder quiet, telling the local news media only that a woman had died at a Laredo hospital after suffering “head trauma.” But when reporters realized the proximity of Ramirez’s and Luera’s bodies, they connected the crimes. News spread through Laredo that a madman was on the loose and that he was using San Bernardo as his hunting ground. What’s more, instead of dragging his victims’ bodies into dense brush, where they would not be discovered for weeks or months—or perhaps not at all—he was displaying them next to dirt roads, as if he wanted people to see what he had done.

Villarreal began monitoring San Bernardo in her Blue Demon, and she begged the women she saw to go home. But most of them told her there was no way they could leave. They needed the money. Villarreal, distraught, made the women promise not to get into vehicles with strangers. She urged them to carry Mace or a switchblade.

Meanwhile, Texas Rangers, sheriff’s detectives, and other cops once again descended on the prostitute blocks, searching for clues to any men who had recently picked up Luera. They got a few more names, which they passed on to Ortiz at the South Texas Border Intelligence Center. He and his team waded through photographs from Border Patrol cameras positioned near the road where Luera had been found. But Ortiz soon reported back that none of the automobiles were owned by men on the list of possible suspects. His duties done for the day, Ortiz walked out of the intelligence center to the parking lot, got into his vehicle, a white 2015 Dodge Ram 2500 pickup, and headed home.

On the evening of September 14, about 36 hours after Luera’s body was discovered, Erika Peña, a skinny 27-year-old with dyed blond hair, was walking San Bernardo when she saw a white Dodge Ram pickup headed her way. Peña knew the driver, who went by David. She liked him, in fact. He had told her he was a federal law enforcement officer, but she had never seen him in uniform. That night, she would later say, he was happy and talkative.

She got into his pickup, and he drove her to his home, explaining that his wife and children were out of town for the weekend. Once inside, they talked for a few minutes as she smoked a cigarette. At one point, Peña asked David if he knew anything about what had happened to her friend Melissa Ramirez.

That’s when he began to “act weird,” she later recounted. He stopped smiling. Why, he prompted, would she ask him about a murder?

He was standing directly behind her. Suddenly feeling nauseated, Peña ran outside and vomited. David cleaned the mess with a garden hose. They got back into the pickup, and David stopped at a gas station to buy her some food. When he returned to the truck, Peña brought up Ramirez’s murder again. Was he sure he didn’t know anything?

He leaned forward, reached into a side compartment of the driver-side door, and pulled out a black .40-caliber semiautomatic pistol. He aimed it directly at her. Peña threw open the passenger door and leaped out of the truck. David reached out and snatched at her shirt, ripping it off as she tumbled to the pavement.

It just so happened that a DPS trooper was parked at a different island at the station, pumping gas. Peña sprinted toward him, screaming that a man was trying to kill her. By then, David had driven away. The trooper took Peña to the Webb County sheriff’s substation, where the Texas Rangers and sheriff’s detectives arrived to question her. She told them everything she knew and then showed them where he lived. The investigators ran a property search on the address. The house belonged to a Border Patrol agent named Juan David Ortiz.

He was born in Brownsville, the oldest of four children raised by a single mother. He attended Gladys Porter Early College High School. According to one of his attorneys, he competed on the swim team and ran cross-country. He was a member of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and was active in the youth group at an Assembly of God church. “He had all the makings of the all-American boy,” the attorney said.

Juan David Ortiz—his friends called him J. D.—was also a patriot. On July 5, 2001, a little over a month after his eighteenth birthday and only two months before the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy as a corpsman and became an emergency medical technician, trained to provide trauma care during combat. He was dispatched to the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center, in Twentynine Palms, California, and was placed with a platoon of Marines who took to calling him Doc. One of his closest friends at the base, Jerry Solis, who was from Laredo, was drawn to Ortiz’s good-natured personality and his devotion to Christian values. Ortiz rarely cursed and didn’t try to pick up women when he went to nightclubs with his fellow Marines. “He was the kind of guy you could trust,” said Solis. “A good man.”

In January 2003, Ortiz, only nineteen years old, deployed with his unit to Kuwait. Two months later, they were sent to Baghdad. Ortiz accompanied a group of Marines who had been ordered to clear some of the city’s dangerous streets. He witnessed intense combat—“dudes who were shot up,” said Solis, “and some dead bodies”—but he was never wounded. On May 4, three days after President George W. Bush’s “Mission Accomplished” speech, Ortiz’s unit was shipped back to the United States, and he flew to Brownsville for a few days of leave.

At the Brownsville airport, Ortiz received a hero’s welcome, greeted by family and friends. His grandma brought balloons. He gave a brief interview to a newspaper reporter, in which he humbly downplayed his combat experience. He said that none of the Marines he treated were seriously wounded. He also said he was looking forward to having a meal of huevos rancheros.

“He didn’t just want to stop the bad guys,” said Erik Aguilar. “He wanted to use his medical skills to help migrants. I know this might be hard to understand right now, but Doc really cared about people.”

During his leave, Ortiz ran into a high school friend named Daniella, who was working in a beauty shop at the mall. The following year, they married in Brownsville—Solis drove down from Laredo to be the best man—and held their reception at a ballroom across the border in Matamoros. In 2005, Ortiz was transferred to Fort Sam Houston’s Navy Medicine Training Support Center, in San Antonio. “He was one hundred percent normal,” said Brandon Caro, a Navy corpsman also stationed at Fort Sam Houston. (Caro now lives in Austin and is the author of the novel Old Silk Road, based on his experience in Afghanistan.) “He didn’t say anything that would make me think something was wrong with him. And he was totally competent at his job. I admired him. I really did.”

While in San Antonio, Ortiz enrolled at the online, for-profit American Military University, earning a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice. In May 2009, weeks before his twenty-sixth birthday, he left the Navy. Among the awards and decorations he’d collected by then were the Joint Meritorious Unit Award, the National Defense Service Medal, and the Rifle Marksmanship Ribbon. Although he had a job offer from the San Antonio Police Department, he decided to join the Border Patrol. “He didn’t just want to stop the bad guys,” said Erik Aguilar, a Marine buddy from Twentynine Palms who lives in California. “He wanted to use his medical skills to help migrants who had been traveling for days in the desert just to get to the United States. I know this might be hard to understand right now, but Doc really cared about people.”

Ortiz spent 58 days at the Border Patrol’s academy in New Mexico. He was required to pass a drug screen, a lie detector test, and a battery of physical fitness exams. He was trained in high-speed off-road pursuit driving and taught to use an agency-issued .40-caliber HK P2000 semiautomatic pistol. He took classes at the academy in criminal and immigration law.

For his first assignment, he was sent to the Cotulla Border Patrol Station, halfway between San Antonio and Laredo. He was initially assigned to chase coyotes (men hired to smuggle immigrants across the border) and drug mules and to detain undocumented immigrants. Ortiz eventually became a member of the Cotulla station’s highway interdiction team, trained to stop cars and trucks suspected of being used for drug trafficking or human smuggling. In his spare time, he took classes at St. Mary’s University, in San Antonio, and in 2013 he earned a master’s degree in international relations.

Ortiz was clearly one of the Border Patrol’s up-and-comers. Only once did his superiors receive a complaint about him: an immigrant whom Ortiz had apprehended claimed that the agent had taken a cigarette from him. (The complaint was dismissed, and no disciplinary action was taken.) In 2014, he passed his Border Patrol review. (To screen for Border Patrol agents who might abuse their power, Congress passed a law in 2010 requiring all agents to undergo a background investigation every five years, which involves credit checks and interviews with family and former coworkers to look for red flags.) A year later, he moved to Laredo.

Occasionally, Ortiz would swap texts with his Marine buddy Aguilar about the rigors of the job. “He said he felt like he was back in Iraq, going to war every day,” Aguilar said. Ortiz even sent Aguilar photos of human bones and skulls that had been found in the desert.

Aguilar told his wife he suspected Ortiz was experiencing long-repressed PTSD from his time in Iraq. He texted his friend. “I said, ‘Doc, you’re a good guy. You need to take care of yourself and your family. Have you thought about quitting the Border Patrol?’ And Doc said, ‘You know I can’t do that. I’m doing my best down here to help all the people who need help.’ ”

If Ortiz was suffering from PTSD, his supervisors didn’t seem to notice. In 2017, he was promoted to intelligence supervisor. At the South Texas Border Intelligence Center, he was tasked with such duties as sniffing out the locations of stash houses and identifying leaders of smuggling and trafficking operations.

By then, Ortiz and Daniella had two young children. The couple bought a newly built, beige-colored stucco home in the San Isidro Ranch neighborhood, in north Laredo, for $240,000. He spent most of his free time with Daniella and the kids. Occasionally, on Saturdays, he hunted or fished with his best man Solis, and on Sundays he and his family attended the First Assembly of God. To those who knew him, it seemed that Ortiz had built a good life for himself.

In early 2018, Ortiz told Solis he had to forfeit the hunting lease the two shared outside of Laredo. “He said that he was having to work too much, that he was under a lot of pressure at his job,” said Solis. “I said, ‘Come on, bro, we love that lease.’ But he kept talking about all the work he had to do.”

During the following months, Ortiz and Solis periodically would meet at the truck yard owned by Solis’s family or at a Buffalo Wild Wings. Ortiz would drink excessively, often five beers or more. “And it was hard to have a conversation with him,” said Solis. “It was like something else was on his mind.” In late spring or early summer 2018, Ortiz told Solis that he had gone to Laredo’s VA clinic, where a doctor had prescribed what Solis describes as antipsychotic medication. “I told him, ‘Man, don’t go overboard with those pills,’ ” said Solis. “ ‘And don’t drink and take those pills at the same time. They will fuck you up.’ But he said, ‘These pills work. I don’t feel bad. I have no stress, no worries. I feel untouchable.’ ”

Later that summer, Ortiz showed Solis a photo on his phone of a young woman. He said he had met her at a Gold’s Gym. Solis was stunned. “I said to him, ‘Ortiz, have you thought about what you’re going to do if your wife finds out you have a girlfriend? Are you willing to lose her and your kids?’ And he said, ‘There’s going to be no problem. My girlfriend knows I’m married, and she’s okay with that.’ ”

On August 30, Solis invited Ortiz to the truck yard to watch a preseason game between the Dallas Cowboys and Houston Texans. Ortiz took a couple of pills and drank several beers. He said little and left before the game ended, explaining that he had to be at work early the next morning.

Four days later, Melissa Ramirez was found next to the dirt road. When Solis saw her photo in the newspaper, he was struck by her resemblance to the woman he had seen on Ortiz’s phone. But he convinced himself he was mistaken. When he heard about the discovery of Claudine Luera’s body on September 13, Solis never considered that Ortiz might be involved in her murder.

“I mean, Ortiz was a churchgoer,” Solis said. “He never once talked to me about prostitutes. If someone had told me that Ortiz was picking up women on San Bernardo, I would have said, ‘You’ve definitely got the wrong guy.’ ”

The investigators entered Ortiz’s house just after midnight and found an arsenal of weapons, twelve in all, including high-powered rifles, pistols, and a shotgun. Assuming Ortiz would flee Laredo, they put out a BOLO (a “Be on the lookout” message) on him.

Ortiz, however, had other intentions. After fleeing the gas station, he’d driven to his house, where he loaded up on ammo, and then returned to San Bernardo—no doubt the last place the police would expect him to go. He picked up 35-year-old Guiselda Hernandez. He drove her up Interstate 35 for twenty miles, stopped at an overpass, demanded that she get out of the truck, and shot her twice in the neck. He then cracked her over the head with what one investigator would later describe as “a blunt object.”

He climbed into his pickup and immediately drove back to San Bernardo. He pulled up beside two women. One of them, 28-year-old Janelle Ortiz (no relation), was a trans woman who had been sleeping under a bridge recently and badly needed money. When Ortiz asked if either of the women would like to be his date for the evening, Janelle stepped forward. He drove her fifteen miles up the interstate and pulled over. He ordered her to get out of the truck and walk behind a pile of nearby gravel. There, he shot her in the back of the head.

Ortiz had killed two women in less than two hours. He wasn’t finished. For the fourth time that night, he headed toward San Bernardo, but he stopped along the way at a Stripes convenience store to use the bathroom, leaving his pistol in his truck. A DPS trooper, alerted by the BOLO, identified his truck and attempted to stop Ortiz as he exited the store. Another officer arrived and tried to bring down Ortiz with a Taser but missed. Ortiz sprinted south on San Bernardo and ducked into a hotel parking garage.

Villarreal was at the scene of another incident when she received tips that San Bernardo had been blocked off. She rushed over, learned that a manhunt was underway, and began livestreaming. Her Facebook followers watched as a SWAT team closed in on the third floor of the parking garage, where Ortiz was hiding in the bed of a truck, using his phone to post two messages on his own Facebook page.

“To my wife and kids, I love u,” read one post. The other: “Doc Ortiz checks out. Farewell.”

His friend Aguilar, who was 1,788 miles away in Sacramento, happened to check Facebook around that time. He read Ortiz’s posts and, afraid Ortiz was preparing to kill himself, immediately called him. Ortiz didn’t answer. He stayed in the bed of the truck for nearly an hour, finally emerging at 2:34 a.m. with his hands raised. He was handcuffed and taken to the sheriff’s substation, where he was read his rights.

At first, Ortiz refused to talk to investigators. Then he requested a photo of his wife and kids. He said that he wanted to keep the picture while he was jailed to await trial. Ortiz explained that he deeply loved his family. He wanted always to be able to look at their faces.

The interrogation lasted for more than eight hours. Speaking in both English and Spanish, Ortiz said he had become frustrated with the Laredo Police Department’s failure to remove prostitutes from San Bernardo, and he had decided to get rid of the women himself—“eradicate all the prostitutes” is the way he put it, according to a source who was at the interrogation. In a matter-of-fact voice, Ortiz admitted that he had murdered Ramirez, Luera, Hernandez, and Janelle Ortiz. He said that he believed he was “doing a service” for Laredo residents by killing the prostitutes, whom he called “scum of the earth.”

Ortiz even admitted that when he aimed his gun at Guiselda Hernandez, she quietly begged him not to shoot, telling him, “Put your life in God’s hands. God will take care of you.” Ortiz, unmoved, stared at Hernandez and pulled the trigger.

At the time, the Border Patrol was under fire for accepting unqualified applicants to fill its depleted ranks. But how, many demanded to know, had a serial killer gotten into the Border Patrol? Hadn’t anyone noticed that Ortiz was deeply disturbed?

The news of Ortiz’s arrest not only rocked Laredo, it became a national headline. At the time, the Border Patrol was under fire for accepting unqualified applicants to fill its depleted ranks. But how, many demanded to know, had a serial killer gotten into the Border Patrol? Hadn’t anyone noticed that Ortiz was deeply disturbed?

“It’s very obvious to me that something is not right here,” declared Laredo mayor Pete Saenz, who pressed for the Border Patrol to come up with a new way to recruit and psychologically evaluate its agents. Congressman Henry Cuellar, whose border district includes Laredo, suggested that the agency hire more professional responsibility officers “so that they can police their own.” Eighteen members of the U.S. House of Representatives, most of them from border states, also weighed in, sending a letter to the commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the agency that oversees the Border Patrol, asking for an investigation to determine whether the agency “missed any red flags that could have prevented these tragedies, such as changes in Ortiz’ [sic] conduct.”

Laredo criminal defense attorney Joey Tellez, who was initially appointed to represent Ortiz, said that Ortiz told him that a VA doctor had diagnosed him with PTSD in February 2018. Tellez said that Ortiz also claimed that the drugs the VA doctors prescribed him had “messed him up.” Ortiz even told Tellez that when he was arrested in the parking garage, he had shouted, “The VA did this to me.”

In the aftermath of Ortiz’s arrest, VA officials would not comment about Ortiz, citing privacy laws. Border Patrol officials also refused to talk about Ortiz except to say that there had been only one unsubstantiated complaint (the stolen cigarette allegation) ever filed against him during his nine years at the agency. “There was nothing in his background certainly that would have alerted CBP [Customs and Border Protection] or have indicated Mr. Ortiz was capable of anything like this,” said Juan Benavides, special agent in charge of the Border Patrol’s Office of Professional Responsibility, in Houston. One source in the Border Patrol’s Laredo sector insisted that Ortiz was “perfectly professional” on the job. “I promise you, we were as shocked as everyone else when he got arrested,” the source said.

What just about everyone involved in the investigation acknowledges is that Ortiz’s killing spree could have been even worse. Because of his position at the Intelligence Center, where different police agencies freely swap information, Ortiz had been able to keep tabs on the investigation of his crimes. Who knows how long he could have gone if Erika Peña hadn’t escaped?

On a recent afternoon, while sitting over a plate of Mexican food at Danny’s Restaurant, a popular Laredo joint, Webb and Zapata county district attorney Isidro Alaniz addressed the rumors about Ortiz’s emotional problems. “I’ve heard all the talk about Ortiz’s PTSD,” he said. “But the evidence shows that Ortiz was a calculating killer. He was a self-appointed vigilante—the judge, jury, and executioner of defenseless women. He wanted those women to die.”

Alaniz, who plans to personally lead the prosecution at Ortiz’s trial sometime next year, stabbed at an enchilada with his fork. “This man went from good to evil. There’s no other way to describe it.”

A few days after Ortiz’s arrest, more than 150 mourners—including the families of Ramirez, Luera, Hernandez, and Janelle Ortiz—gathered for a vigil organized by Villarreal at San Agustín Plaza, in downtown Laredo. Several people wore T-shirts emblazoned with the names and photographs of the murdered women. Others held signs that read, “We want justice for all victims.” Villarreal distributed white candles. She arranged for guitarists to play Christian music and for a local pastor, Manuel Castillo, to speak. He read from the book of Psalms: “The Lord is close to the brokenhearted and saves those who are crushed in spirit.”

In some places, perhaps, there might not have been a vigil for murdered prostitutes. “But what you have to understand is that all of these women grew up in our community,” said Colette Mireles, one of Claudine Luera’s sisters. “We loved them and cared for them. We always felt hope that they would change. You might not understand this, but we never turn our backs on our loved ones just because they are going through hard times. That’s part of our culture down here.”

Indeed, Villarreal’s Facebook page was filled with notes from people who knew the victims. (“My beautiful best friend. I love her so much when I was in middle school with her,” someone wrote about Hernandez. “My Deepest Condolences to the 4 families,” wrote someone else.) The families of Luera, Hernandez, and Janelle Ortiz held funerals at Catholic churches. Ortiz was buried in a ruby red dress, with a red flower tucked behind one ear. Ramirez’s mother, Cristina Benavides, could not afford a burial plot in a Catholic cemetery; neighbors showed up at her trailer to donate money for Ramirez’s cremation. Benavides placed the wooden urn in the kitchen, next to a Bible and a photo of Ramirez draped with rosary beads and a gold cross necklace. In the photo, Ramirez is smiling. A few strands of hair fall over her eyes. “Ella sigue siendo mi niña hermosa,” Benavides said (“She is still my beautiful girl”).

As for Peña, her aunt Marcela Rodriguez said she was so traumatized by her encounter with Ortiz that she would not even venture into public. She was barely eating and was having trouble sleeping. “She has nightmares, all through the night,” Rodriguez said. “In her nightmares, Ortiz is out of jail and looking for her. He’s driving his big white pickup truck and she cannot get away.”

Ortiz refused numerous interview requests from reporters around the country who wanted to travel to the Webb County jail to meet him. He didn’t make his first public appearance until this past January, nearly four months after his arrest, when he was led into a courtroom for his arraignment. His wife, Daniella, wasn’t there. According to Tellez, Daniella was distraught that she had encouraged her husband to see a doctor at the VA clinic. She had come to believe that the medications he was prescribed had caused his troubles. But Solis did show up, slipping into a bench in the back, hoping to make eye contact with Ortiz. “Just to let him know I was there,” he said.

Wearing a short-sleeved orange jumpsuit and shackled at the wrists, waist, and ankles, Ortiz shuffled into the courtroom. The hearing only lasted a few minutes. Ortiz did look in Solis’s direction, but he quickly looked away. Ortiz pleaded not guilty to charges of capital murder and was then led back out of the courtroom.

Ramirez’s mother, Benavides, shouted, “¡Maldito asesino!” (“Damn murderer!”) Other relatives stared at Ortiz in shocked silence. “He smirked right back at us,” Mireles said. “He didn’t have an ounce of remorse. I’m not trying to be dramatic, but he looked like the Devil.”

Later that day, Solis went back to his family’s truck yard and sat in a chair, “thinking, trying to connect the dots.” How, he asked himself over and over, could such a conscientious father and husband turn into a depraved monster? How could someone who had spent his career helping others have gone on a killing rampage? But he finally gave up and went back to work. “I’m not sure,” he said, “that there are any dots to connect.”

This article originally appeared in the October 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Serial Killer of Laredo.” Subscribe today.