Nobody came to Navarro cheer to be famous,” Monica Aldama said in her soft twang.

She was sitting in her office, a long, narrow treehouse of a space tucked away on the second floor of the gym at Navarro College, in Corsicana, about an hour southeast of Dallas. The wall behind her desk was red and lined with trophies, and I recognized it as the spot from which she’d given many interviews on Cheer, the Netflix docuseries that rocketed her to fame. A large piece of what looked like butcher paper was taped across a fluorescent fixture in the ceiling—a diffusion filter placed by the camera crew to create a more flattering light—and I couldn’t tell if it was still there because she hadn’t noticed it or because Netflix might be coming back.

Navarro cheerleaders may not have been looking for fame, but fame showed up anyway. Cheer won three Emmys and legions of fans as it trailed the junior college athletes on the bone-crunching path to the National Cheerleaders Association (NCA) College Nationals, often referred to by the name of its beachside Florida locale, Daytona. Cheer was a pandemic-era smash, elevating the dazzling but little-known sport of college cheer to the level of national obsession and reframing cheer itself from a sideline spectacle at football games to a thrilling and often perilous main event.

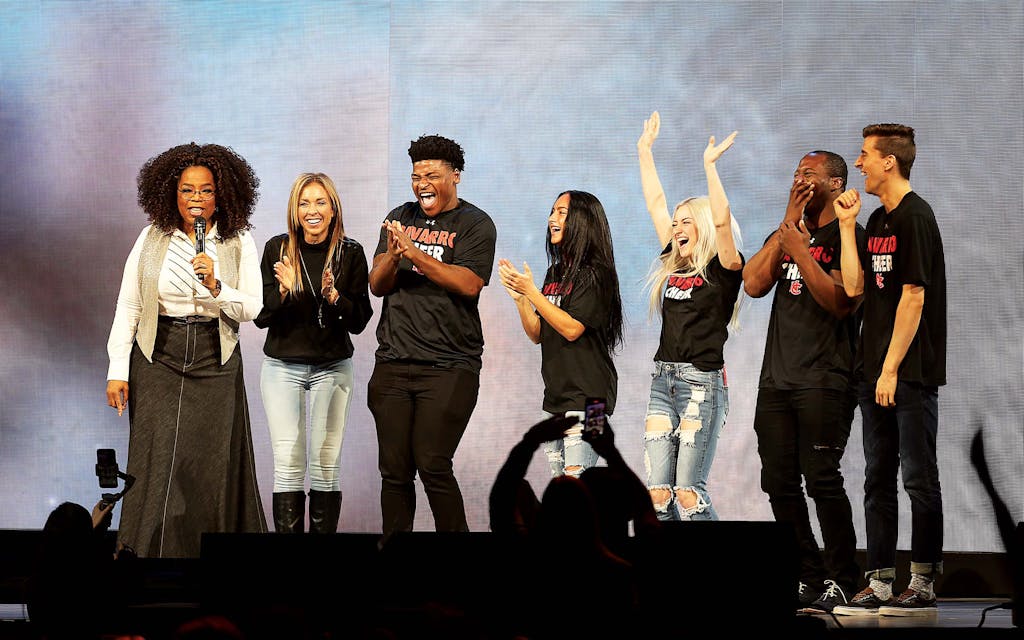

Oprah and Reese and Ellen were fans, back when Ellen DeGeneres was a celebrity you wanted on your side. The fame brought global recognition and hordes of social media followers and experiences you could find on Make-A-Wish lists. Aldama competed on Dancing With the Stars. The team was gently lampooned on Stephen Colbert’s show and on Saturday Night Live. But fame had a shadowy side.

By the time I first sat down with Aldama, in May 2022, bad news had been following the Navarro team for more than a year, through scandal after scandal. “Ex-‘Cheer’ star Jerry Harris gets 12 years for seeking photos and sex” (NPR). “ ‘Cheer’ star La’Darius Marshall is ‘safe’ after alarming post” (Today.com). During one grim period, the school blacked out the gym windows so paparazzi couldn’t spy on team members as they practiced. Paparazzi! In Corsicana! A town of 25,000, where it seemed the only bustle had been from trains barreling through. Until Cheer, Corsicana’s main claim to fame had been the fruitcake at Collin Street Bakery (“the world’s best fruitcake for over 125 years”). Fans had been clamoring for a third season, but Navarro college officials confirmed that they were not interested in pursuing one.

As we chatted, rain pitter-pattered on the roof of Aldama’s office, which was decorated with evidence of an illustrious program that dominated long before the cameras rolled into town—fifteen national championships since she took over, in 1995. A photo spread from a 2000 issue of American Cheerleader magazine decorated one shelf of a cabinet; a poster-size collage of the 2018 championship team leaned against the wall, waiting to be hung along with posters from other winning seasons, as if she’d lost her hammer for four years. The office was decidedly feminine, with a black futon whose fuzzy silver-gray throw pillows reminded me of the college dorm aisle at Target. A bookshelf in the corner displayed a picture of her family—husband Chris and kids Ally and Austin—and a tiara given to her by her athletes, a playful riff on her nickname: the Queen.

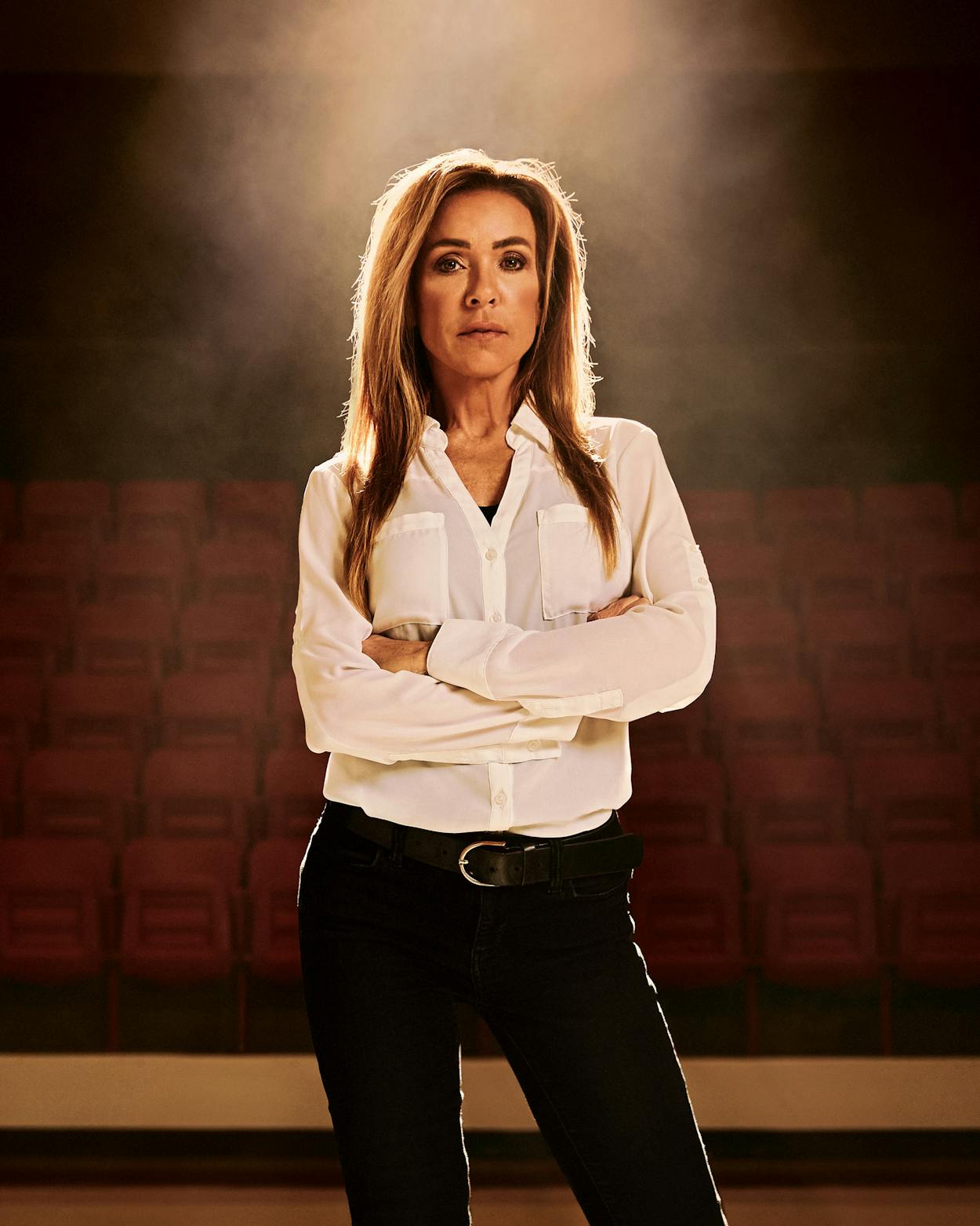

In person, the 52-year-old Aldama was more easygoing than the taskmaster I’d gotten to know on Netflix, with a reserve that could read as aloof but was probably more like shyness, a lack of big-city bravado. She had a generous laugh and a down-to-earth demeanor that seemed unwarped by her tango with the stars. “Coach” is a genre of fashion known for golf shirts and khakis, but Aldama was stylish—silky blouses and snug jeans with boots, her signature look. She wore boots so often that cheerleaders learned to tell her approach from the clickety-clack.

Reflecting on the end of Cheer, Aldama sounded somewhere between disappointed and relieved. Only a few weeks earlier she’d celebrated a decisive victory at Daytona, but since the Netflix crew hadn’t been there to capture it, fans wouldn’t see the team rise from the ashes of season two, in which they suffered a crushing loss to their archrival. But the end also meant no more cameras, a needed break from the spotlight. “I’m good with it,” she said of the show’s end, opening her manicured hands wide as if she were releasing invisible reins. “God’s plan.”

What Aldama didn’t realize was that the drama wasn’t done yet. Another scandal was brewing, and it would become the fight of her career. She would stand accused of attempting to cover up a sexual assault and get suspended from her sport. Even the subreddit page for Cheer turned on her—thousands of strangers once united by fandom were now essentially unanimous in their scorn. “Monica is absolutely disgusting,” read a typical comment. “She knows this s— is going on and keeps it hush hush for trophies.”

In the snug confines of her office, she had no clue this was coming. Sneaker squeaks from the gym drifted into the room, which smelled of new paint. I’d been turning a question over in my mind in the days leading up to our meeting. Did she regret doing Cheer? To be more specific: was it possible the fame that opened doors for her athletes had also opened trapdoors beneath them—and her? I often thought of a John Updike line, “Celebrity is a mask that eats into the face.”

Aldama crossed her legs, bouncing one lightly as she contemplated this. “I don’t know the answer to that question,” she said in a small voice.

Audiences love an underdog story. That was Navarro once: a little-known junior college in a once prosperous oil town with a scrappy team of misfits from hard-luck childhoods building a human pyramid to glory. But Navarro had become a machine so sleek, so hyperbolically praised, that the team was the assumed champion. And if there’s anything the audience loves more than an underdog story, it’s what you might call an overdog story.

It happened at Baylor University, in Waco, where Coach Art Briles ended his improbable run in a fireball of shame. It happened at Penn State, where Coach Joe Paterno fell from grace alongside defensive coordinator Jerry Sandusky, found guilty on 45 counts of child sex abuse and sentenced to thirty to sixty years in prison. The online spectators gathered in comment sections and sharpened their blades: Would Aldama be next? Did she deserve to be next?

An end that had once seemed impossible began to appear likely: the Queen, dethroned.

Monica Holcomb wasn’t born in Texas, but she sure looks and sounds like she was. Her family moved from rural Alabama to Corsicana in 1978, when she was in first grade, and she spent her childhood sliding between those two places, visiting relatives in the heart of the South and going to school in the Lone Star State. Her paternal grandmother sang in the church choir; her maternal grandmother was a foulmouthed firecracker. She became a hybrid of the two: a proper lady unafraid to deploy an f-bomb.

She sought her dad’s approval above all else. He ran plants that refurbished train wheels, a reminder of the town’s glory days in the early twentieth century, when the Southern Pacific and the Trinity and Brazos Valley Railway rattling through were enough to make Corsicana a major Texas hub. Billy Holcomb was the kind of disciplinarian who didn’t need to discipline much. He just snapped his fingers, and she complied.

She was popular in school: a cheerleader, a softball player, class secretary. She got a job at Catfish King when she was old enough and wrote little chants to greet drive-through customers. She dreamed of becoming a corporate CEO in New York City, but after graduating from the University of Texas at Austin, she returned to Corsicana and married her high school sweetheart.

“She got my head straight,” Chris Aldama told me, sitting near a Texas flag in his office in the Navarro County Community Supervision & Corrections Department, where he’s the director of adult probation. Chris is affable and good-looking, the kind of low-key dude who looks like he fishes on weekends and plays guitar in a band that performs covers of Fleetwood Mac and the Cure. He met his wife in middle school. He was a catcher on the little league baseball team, and they joke that their first interaction was Monica behind the fence yelling at him.

Chris wasn’t always on the straight and narrow. Back in college, he was a wayward partyer fortunate to pass even his bowling class. “She got me through,” he said of his wife. They both attended Tyler Junior College, but he went to what was then called Southwest Texas State University (it became simply Texas State in 2003) while she studied finance at UT, where she graduated in three and a half years.

Redirecting lost students would become a specialty of Aldama’s when she took a low-paying gig running a cheer team at Navarro College that nobody had ever heard of. A friend called one day to let her know the cheer coach was leaving, and Aldama thought the position could be a stepping stone to something else. At least it would mean escaping the grind of her job as sales manager at a computer company.

She started in the mid-nineties when cheer was evolving from a casual popular-girl pastime into a demanding, legitimate sport. The late eighties saw the birth of all-star cheer, separate from school-based cheer programs, with their pompoms shimmying under Friday-night lights. All-star cheer was a rigorous endeavor in which girls and boys (but mostly girls) trained from a young age to compete in local competitions that ate up entire Saturdays and pushed skills to a level unseen on high school sidelines. Meanwhile, college cheer squads such as those at the University of Louisville and Oklahoma State University were upping the game with hard-core tumbling and death-defying stunts that transformed the annual competition in Daytona into a serious throwdown.

When Aldama arrived, the Navarro Bulldogs weren’t close to that level. She had no legacy to maintain. She drove the team to an early competition in a beat-up van. In what seemed like an apt metaphor for the whole grim endeavor, she had to pilot that fifteen-passenger behemoth through the labyrinth of downtown Dallas on a day when it was snowing, only a week or two after starting her gig. “I was terrified,” she told me. “I was like, I don’t know what I’m doing.” They made it anyway.

She was 22 years old, younger than some cheerleaders on the team. “Everybody thought she was beautiful,” said Marcus Hodges, who joined the Bulldogs in 1997. Those pretty hazel eyes, the slender body. Dudes couldn’t help wondering if they had a shot. “We’re college guys!” he said, laughing. But no. “She was all business.”

She was stricter in the beginning, maintaining a vigilant separation between teacher and student. She was not their friend. She did stunt with the boys, though, letting them hoist her in the air by one foot. “She was a good flyer,” Hodges said.

The team grew in number and strength. One of Aldama’s innovations was to craft routines that maximized the judges’ score sheet at Daytona, a version of moneyball for college cheer. She was working toward her master’s in business administration at the time, attending night classes at the University of Texas at Tyler, and she applied the analytical skills she was learning to her job on the mat. She noticed that most teams were simply trying to wow the crowd, to outdo one another with eye-popping stunts. But they had an entire score sheet to work with, and they left points on the table. It wasn’t unusual for Aldama to spend a whole practice on one transition. Details mattered. Every skill had to be nailed, but every count had to be considered. Navarro won its first national championship in 2000—and kept winning.

That same year, the Kirsten Dunst comedy Bring It On became a box office hit, capturing the razzle-dazzle of competitive cheer and branding it on the imagination of a younger generation. Over the next decade the sport exploded, with lucrative cheer gyms taking their place alongside gymnastics and dance facilities and “cheerlebrities” gaining huge audiences in the brave new era of YouTube and Facebook.

By then Dallas had become the epicenter of the cheer world. The pioneer of modern cheer was a graduate of Southern Methodist University named Lawrence Herkimer, who patented the pompom, though he later insisted on spelling it “pompon” after someone told him “pompom” had vulgar connotations in other languages. Herkimer is the namesake of the “Herkie” jump, where a cheerleader leaps in the air with one leg bent and the other extended. He also founded the National Cheerleaders Association, which began as a series of training camps and cheer clinics he ran with the help of Jeff Webb, a former yell leader from the University of Oklahoma. The two parted ways, and Webb became Herkimer’s chief competitor. In 1974 he launched Varsity Spirit, the monolith that currently rules the cheer kingdom. In 2004 Varsity acquired NCA; the student had become the master.

The NCA nationals were based in Dallas when Aldama began coaching, but they moved to Daytona in the nineties, creating more of an event—the beachside locale, the spring break weather. Over the next decade, as the sport spread its tentacles into colleges and all-star practice facilities and the deep pockets of supportive parents, Varsity came to dominate the sport’s many commercial products: uniforms, sports bras, shoes, hoodies. In 2018 Varsity’s parent company, Varsity Brands, was purchased for a reported $2.5 billion, by Bain Capital, a powerful private equity firm cofounded by Mitt Romney, the U.S. senator from Utah.

In 2007 Varsity also formed the Dallas-based nonprofit USA Cheer. The cheer world has long nurtured dreams of seeing its athletes compete at the Olympics, a goal that may well be realized at the 2032 games in Brisbane, Australia. USA Cheer was one key to that master plan. A governing body could tighten the reins of a sport that had initially been running wild. USA Cheer now oversaw the official safety guidelines, along with eligibility requirements. In 2003 Varsity had started U.S. All Star Federation (USASF) to regulate the largely private all-star side of the enterprise, while USA Cheer oversaw the whole sport, including high schools and colleges, and if all this sounds confusing, it was. The point is that as all-star gyms proliferated and as more colleges flocked to Daytona, Varsity sat atop the throne.

Dallas also happens to be the birthplace of modern-day NFL cheer, since the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders transformed sidelines in the seventies with skimpy uniforms and flirtatious dance, a blueprint that shaped cheerleading across professional sports. A bevy of Dallas sports franchises meant a bevy of young women showing up to dance studios in sneakers and booty shorts.

This kind of cheerleader wasn’t cheering in the traditional sense, with bullhorns and the old sis-boom-bah. NFL cheer evolved from the high school drill team, with its precision kicks and fine-tuned choreography—the Radio City Rockettes in white cowboy hats. All-star cheerleaders, tumbling and soaring in stage makeup with giant bows perched in teased ringlet hairstyles reminiscent of Toddlers & Tiaras, have been known to look down on NFL cheerleaders, whose excellence demands both athleticism and va-va-voom sex appeal. But whichever branch of cheer you preferred, Dallas’s singular mix of sorority-style etiquette, pageant talent, and male-dominated sports mania bred an entirely original female warrior. Her jump split and her lip gloss were both on point.

It’s no coincidence that Navarro’s main competition in the junior college division at Daytona would come from the same part of Texas. Trinity Valley Community College, in Athens, is forty miles east of Corsicana, off Texas Highway 31. When Navarro started competing at Daytona, in the late nineties, there were only a few categories: large coed, small coed, and all-girl. There was no junior college division, so Navarro competed against about twenty teams, only ten of which advanced to the finals. But as the sport expanded, so did the competition’s hierarchy. The NCA ultimately introduced a “junior college” and an “intermediate” division, splitting big showdowns into smaller contests that vastly improved a college’s shot at a trophy—thus clearing the way for more entrants and, presumably, more profits. Teams once thwarted by the two giants of the advanced junior college division slinked away to categories with lower-level skills until Navarro and Trinity Valley were often the only ones left: Joe Frazier squaring off against Muhammad Ali each April.

Aldama’s dreams of success in New York had long faded by this point. She bought a cheer gym close to Navarro, an investment that came with a professional side bonus: her squad could practice there at night. The strain of all this—the night school MBA followed by her children followed by the emergence of her squad as a dominating force—took its toll. She and Chris divorced in 2006. Their spats were typical: she always had to be right; they started keeping score, any romance curdled by daily resentments. But they cautiously started dating again a year later, and got remarried a year after that. Growing up was preferable to growing apart.

The same hardheaded drive that made Aldama’s marriage difficult proved a key element in her teams’ successes on the mat. The Navarro Bulldogs won the Grand National title in 2012, meaning their Daytona score was tops across all divisions, a first for a junior college. That’s about the time the kids started calling her Queen.

Greg Whiteley was looking for a new documentary subject. This was around 2018, and the director, born in Utah and raised in the Mormon church, had tracked junior college football teams for the Netflix series Last Chance U, a 2016 sleeper hit. Last Chance U was a sports saga told with a storyteller’s eye, less Hard Knocks and more Friday Night Lights—not the crowd-pleasing TV show but the 1990 nonfiction book by Buzz Bissinger, a sobering account of sometimes troubled teens in small-town Odessa finding purpose on the field. In the first season of Last Chance U, filmed at East Mississippi Community College, we meet a promising young athlete whose parents were killed when he was five.

Whiteley heard about Aldama’s unlikely success in competitive cheer, and by the time they met over a conference call, in late 2017 or early 2018, he was pretty sure he’d found his next show. She spoke with such depth and clarity about cheer; she projected confidence. Aldama thought a docuseries could be an education for viewers at home. In the public imagination, cheer was still rah-rah and “Go team!”—not a sport at all. But competitive cheer was bruising and physically grueling. A 2019 Pediatrics study on concussions in school sports placed cheerleading second, behind only football, for the rate of concussions sustained during practice. Aldama’s athletes broke bones and suffered head injuries, but they also discovered a fortitude they didn’t know was in them—the resolve to get back on the mat.

Filming on the first season began in January 2019, as Navarro beat a path to Daytona. For the athletes, the sudden appearance of a boom mic and camera was weird at first, until it became normal. One team member told me the strangest part was that the team had to practice in silence. Loudspeakers usually blared Top 40 hits as athletes practiced their back tucks and partner stands, and team members sang along and danced playfully during breaks, but such noise would create problems for the sound and video editors in postproduction. The only soundtrack became grunts and thuds and the occasional shriek.

The danger of cheer is no joke. Throwing hundred-pound humans into the rafters, in what’s known as basket tosses, doesn’t come without risks, an aspect of the sport that’s become controversial. One day Aldama’s team was practicing an elaborate human pyramid when a flyer, the lightweight gymnastic athlete who tops a pyramid, was tossed up to her position and landed a bit off. One false move triggered a controlled landslide that crumbled the entire pyramid to the ground. The shot is featured at the beginning of Cheer’s first episode.

Aldama figured the series would hit big in their small world and get ignored everywhere else. That was how it went with college cheer, a niche subculture with rabid fans but so little mainstream attention that even the big event at Daytona was broadcast only on a Varsity pay-service app.

Instead, the show blew up. Two weeks after its debut on January 8, 2020, Reese Witherspoon tweeted about Cheer, signaling to her two-million-plus followers that it was the show to watch. “When Coach Monica said she had a lot of career choices but all she wanted to do was coach these @NavarroCollege Cheerleaders, I started to think about all the female coaches who we never see in movies or TV that are changing kids lives,” she wrote.

A few days later, Aldama and 22 team members flew to Los Angeles to perform on The Ellen DeGeneres Show. Aldama and three of Cheer’s breakout stars even got to sit on the sound-stage couch next to Ellen. Among them was Jerry Harris, whose journey to the elite Daytona squad made him a hands-down fan favorite. The Navarro team includes forty cheerleaders, but only twenty compete for the title at Daytona. Although Harris would eventually make the cut after a teammate’s injury, he spent early practices shouting his over-the-top enthusiasm from the sidelines, a delightful motivation ritual called mat talk.

When Ellen asked him to demonstrate mat talk, the ever-accommodating Harris, who had lost his mother to cancer back in high school, stood up and screamed at the talk show host: “Let’s go, Ellen! You got it! Push!”

Those same lucky four filmed a comic sketch for The Late Show With Stephen Colbert called Mat Talk for Regular People, where Coach Monica rubbed the arm of a sad-faced cubicle dweller. “I picked you to send this email for a reason,” she said.

That could have been the end of it, and it had been a hell of a ride. But March 2020 brought a plot twist no one saw coming.

When the pandemic shut down the world, Cheer was the perfect feel-good story for a feel-bad time, an expertly modulated feast of visual derring-do and personal struggle. The show was already a hit, but the pandemic made it a phenomenon. The addictive docuseries upended the cheerleader’s pampered blond stereotype; these were not children of privilege but misfits seeking a home. In a country badly divided, Cheer was a sympathetic and casually diverse portrait of a small town, where church on Sunday and flamboyant gay men could peacefully coexist.

As the show’s moral center, Aldama was tough but compassionate—the mother we needed. She’d dropped the sometimes withering force field of her younger years. Two boots firmly planted in middle age, she could radiate maternal warmth when it was needed and give a firm handclap when it was not. “I’d take a bullet for her,” Morgan Simianer, a petite and pretty brunette flyer, tells the camera. The loyalty wasn’t just about winning Daytona. In scene after scene, we watch Aldama preach the values of education: go to class, study hard, write down appointments in your calendar. Here was a woman modeling the timeless virtues of self-determination, personal responsibility, supporting your team.

Harris wasn’t the only cheerleader with a poignant backstory, and Cheer’s main characters shared theirs with unusual candor: wild child Lexi Brumback, tumbling her way out of teen rebellion; La’Darius Marshall, streetwise showstopper rising from poverty. It would be downright ornery not to root for their success, and Aldama was not merely coach but also their second mom. Perhaps no one exemplified this dynamic better than Simianer, whose mother left when she was little. In episode five, we learn that after her father remarried and started a new family, the tension became bad enough that by high school, Simianer and her brother were living alone in a trailer. Her ascent to the top of the pyramid—“top girl,” in industry lingo—might be the most inspiring subplot in an inspiring show.

Netflix signed on for a second season, and the publicity juggernaut kept rolling. Ellen DeGeneres brought Navarro back to teach model Kendall Jenner, a “huge fan,” how to perform a prep stunt, where two male cheerleaders held her feet at chest level as the lanky reality star nervously thrust both hands in the air. The talk show host loved Jerry Harris and his mat talk so much she enlisted him to work the red carpet at the February 2020 Oscars. “How does it feel to be the coolest man in the world?” Harris asked Brad Pitt, who coolly scoffed. Harris was impossible not to love. Those puppy dog eyes, the squealing enthusiasm for anything, everything. March brought the pandemic—an end to travel as well as the 2020 Daytona season—but the invitations never stopped. In June, Harris joined presidential candidate Joe Biden for an Instagram chat, part of the Democrat’s attempt to reach young Black voters.

Aldama got rare opportunities too. She was cast on the twenty-ninth season of Dancing With the Stars, a show she watched so often she’d named a pyramid after it. There she was, little Monica Holcomb from Corsicana, on a roster that included basketball great Charles Oakley and the rapper Nelly. She sold a book to Simon & Schuster, a memoir that was a compendium of cheer wisdom. In that book, Full Out, she explains how the human pyramid is a lesson in working together. Americans tend to see our paths as individual, but we’re all connected. If one person misses their mark, the entire formation can collapse.

When it came to the Navarro team and its rise to the top, that is exactly what happened next.

She posed for the camera in a royal blue gown that swished at the bottom but was corseted up top, with silver embroidery and a plunging neckline covered in flesh-toned mesh like the kind worn by figure skaters. Her honey-brown hair twirled past her shoulders, bangs drawn back in a barrette. She didn’t look like Coach Monica, but maybe that was the point.

It was September 14, 2020, the day of Aldama’s Dancing With the Stars debut, and she was all nerves. She’d been in Los Angeles about two weeks, and the hustle of opening night was like nothing she’d experienced, allowing no time even to check her phone. Leaving the safe confines of Corsicana for an indeterminate stretch of time in Hollywood had been a risk but also the chance of a lifetime. She’d placed a former cheerleader named Kailee Peppers in charge. Daytona prep was still months away, and Navarro’s fall sports schedule (when her team cheers from the sidelines) had been postponed because of COVID, so she figured not much could go wrong.

During dress rehearsal, an executive producer approached. Had Aldama seen the headlines? No, she’d spent the day eating her own insides and getting shellacked with makeup. The producer handed her a phone. On the screen were words so disorienting that later she’d be unable to recall which news outlet it was or what the headline said—only the thunderstrike of the information.

TMZ screamed in large point size: “ ‘CHEER’ STAR JERRY HARRIS ALLEGEDLY SOLICITED MINORS FOR SEX,” kicking off an outpouring of TV, radio, and online coverage. Aldama didn’t even have time to figure out what was happening. A dress rehearsal was immediately followed by the live taping, where she performed a foxtrot she’d barely learned. Her partner, Val Chmerkovskiy, a Ukrainian-born professional dancer, whisked her around a dance floor lit by a kaleidoscope of spotlights. She looked a bit stiff and out of place, which she certainly was, although she still placed fifth out of fifteen. The next morning, when she arrived at the studio for rehearsal, a TMZ camera greeted her. She thrust out one hand. Not today, Satan.

A bombshell had detonated back in the real world. “Jerry Harris—one of the cheerleading stars of Netflix’s uber-popular show ‘Cheer’—is being investigated by the FBI for allegedly soliciting minors for sex,” read TMZ’s opening sentence. The story would later be updated to clarify that the allegations involved no physical contact. But a bomb, once dropped, cannot be undetonated.

The fan favorite became the villain fast, and though it would take time for facts to trickle into the swamp of online outrage, what became clear is that Harris, then nineteen, had engaged in sexually explicit text exchanges with twin brothers he knew from the cheer world. “Would you ever want to ****,” read a Snapchat, as quoted by TMZ. The boys, at the time, were thirteen. Harris ultimately pleaded guilty to federal charges and was sentenced to twelve years in prison.

The case of Larry Nassar, the former women’s national gymnastics team doctor convicted in 2018 of criminal sexual conduct after the testimony of more than 150 victims, had rocked the gymnastics world, exposing a trail of violations that were either enabled or ignored. The Harris case was the start of the cheer world’s own reckoning, and though news items often roped the men together, their trespasses were quite different. Nassar was a doctor, entrusted with the safety of young girls. Harris met the twins not through a place of employment but through the internet and later at cheer events. Still, the headlines rattled an industry that once seemed like a safe haven. Shortly after, USA Today reported that nearly 180 individuals affiliated with cheerleading had prior sex-related charges.

Cheer is unique in group sports: boys and girls mix on a team with close bodily contact. Cheer gyms employ college athletes to help with kids and teens, who can range from six to nineteen years old. The boundaries between mentor and friend can get awfully blurry in those after-hours practices. Not everyone maintained Aldama’s line of demarcation.

Scandals began to ripple across the country. The founder of a popular South Carolina chain called Rockstar Cheer died by suicide shortly before a lawsuit dropped, alleging he and other coaches sexually abused minors. The chain was shuttered.

Navarro College was not immune to this scrutiny. “2 men who appeared on Netflix’s ‘Cheer’ accused of separate sex crimes involving minors,” read a CNN headline, although one of them, Robert Scianna (charged with using an electronic communication device to solicit sex), wasn’t on the Navarro team at all. He was a popular all-star cheerleader who was arrested in Virginia and had a brief cameo on the show, at a nighttime photo shoot with squad star Gabi Butler. Scianna pleaded guilty to the charges in 2021.

As for the show Cheer, when the second season aired in January 2022, the series seemed to unfold in an alternate universe: camera flashes and a Good Morning America appearance were interspersed with grim-voiced news anchors reporting on Jerry Harris. “I went home after the show and pretty much cried myself to sleep,” Aldama says in the fifth episode, sitting at her desk in a black silk blouse. She speaks in a low and contemplative voice. “I have all these emotions that are fighting each other.”

Commentators had a field day with that one—no clear condemnation, no “I stand with the victims” (though she had shared that sentiment on Instagram shortly after the news broke)—but it’s worth considering the options she faced: Condemn Harris and she’d be turning on someone who’d been like a son. Express compassion for him and she was an enabler, part of the problem. Each path led to loss, and (spoiler alert) the season did too. Navarro placed second to rival Trinity Valley Community College, whose sweat-soaked road to Daytona was also captured by Netflix cameras, so the audience, however disappointed by Navarro’s defeat, could feel a bit vindicated as well. Score one for the new underdog.

The season also tracked Aldama’s fallout with La’Darius Marshall, an exuberant but volatile cheerleader whose emotional stability teeters over the episodes, from clapbacks and eye rolls during his one-on-ones with the camera to “I’m over it” declarations while he fishes near his Florida home, where he retreated after quitting the team.

He was raised by a neighborhood caregiver, known as Miss Edeora, and an armchair psychologist wouldn’t have to search the cushions for long to theorize that Aldama’s abrupt absence that fall might be a repetition of his childhood trauma. Away from the cameras, though, the drama was more complicated. Aldama says Marshall was going through an operatic breakup with his longtime boyfriend that season. As compelling as Marshall could be on the screen, he was eruptive to a degree that tried the patience of even those who loved him.

Aldama didn’t give up on him. The series ends with the two making a fragile peace in a dimly lit Daytona hotel room, a conversation so intimate I wondered if I should even be watching (though I was unable to turn it off). But when the show finally aired, Marshall told a different story on TikTok, Twitter, and Instagram. “She and the rest of her crew were bullies and never deserved my hard work and determination,” he said of Aldama, whom he called mentally and physically abusive.

When I first met Aldama on that drizzly day in May 2022, a few weeks after the team’s fifteenth national win at Daytona, she clickety-clacked in snakeskin boots with kitten heels into the Across the Street Diner, in Corsicana’s quaint downtown. I’d anticipated customers pausing at the table for selfies, the servers making a fuss. But people came and went, the waitstaff too familiar with their hometown hero to remark on her arrival. She came here all the time.

She looked polished but slightly spent. June would bring the launch of the first ever Cheer tour, a live multicity event with an elite cast of current and former cheerleaders. I’d assured Aldama I wasn’t there to talk just about the scandals—Jerry and La’Darius, that was all interviewers asked about—but she talked about them anyway. Marshall, in particular, weighed on her. Another surrogate son. He’d once celebrated Thanksgiving with the Aldamas after she learned he wasn’t going home for the holiday. They took pictures on the lawn, Austin and Ally next to the handsome cheerleader with his megawatt smile.

Referring to Marshall’s social media posts, she told me, in a voice that was less defensive than resigned, “He said all these things about me that are completely untrue.” She’d responded to none of his accusations publicly. “What am I going to say? That he’s completely unstable?”

At the time he was working at a cheer gym in Florida, though not for long. He would take another job in Utah, where he went to heal, something Aldama very much wanted for him. Come to think of it, she didn’t look spent so much as heartbroken.

Cheer warmed hearts because Aldama often helped troubled kids find purpose and direction. Now some of those troubled kids were proving . . . very troubled. In the past such turbulence went largely unnoticed; now it became national news. After lunch, we slid into her white Ford Expedition, and she drove to the nearby campus, wipers thumping as she told me Navarro is also known for its soccer and volleyball teams, and it’s mostly a commuter school. At the gym we stepped through double doors plastered with an enormous cartoon bulldog.

As we toured the facility, empty after the spring semester’s end, she talked a lot about her family. Her husband still mowed their lawn, a point of pride. Her daughter, Ally, was engaged to her high school sweetheart, a football star at Southern Methodist University who would soon sign with the Indianapolis Colts. Ally was enrolled in SMU law school and had earned her business degree from SMU in just three years. Monica’s son, Austin, had graduated from Texas Tech University in three years with a degree in public relations, but he had his father’s laid-back genes. He’d returned to Corsicana and was now working as her personal assistant. (Austin had set up my interview with his mother after I lost traction with her high-profile publicist.)

Family time was the only downtime Monica wanted. She loved game nights, she said, and I had visions of Pictionary and charades, but she also meant football games. Alabama was her team, even though it was a presumed victor, a demolishing force. “Nobody wants a team to win over and over again,” she said. Same with Navarro. She’d been a target since her athletes started their streak of success. “Then the show came out, and I became a target on a level I never knew existed.”

Online commenters insulted her coaching. (Too many injuries.) Many criticized her long, straight hair and French-tip manicure. (Not fashionable; get with the times.) Even before the Harris scandal, she was called a bitch, an egomaniac, a desperate manipulator who took wounded birds under her wing. It was hard to imagine a male coach—vein-popping screams from the sidelines, headsets slammed to the ground, driving the athletes to run until some of them puked—receiving such microscrutiny.

I spoke to more than a dozen former Navarro athletes. The worst thing I heard was that Aldama once threw an iPad onto the mat. And there was one day, right after the cameras departed, when she yelled the f-bomb over and over again, finally free of recording devices. She chewed students out, yes. Her occasional anger could be scary, maybe because her normal mode was so even-keeled. One former athlete remembered the time she’d kicked him off the team after smelling liquor in his Sonic cup while they were practicing a dangerous stunt. Marshall later spoke about this incident on TikTok, except in his version, Aldama also choked the student with her hands. When the kid popped into the comments on TikTok to say that it didn’t happen that way, he says Marshall blocked him.

Aldama still had a lot to celebrate. The team hadn’t merely won nationals a few weeks prior; she told me they’d earned the highest score ever for any team at Daytona. Aldama had stood at the lip of the stage, pounding the mat like a headbanger at a Def Leppard concert, something she does to let them know they’re nailing it. “A lot of what we do is for a feeling—when you hit that routine, when you’re announced as a winner. But that feeling of losing is motivation too.”

All year strangers in Corsicana had approached her: Are you gonna win? Are we taking Daytona? They only meant to be supportive, but the fear of letting everyone down—her team, her town, the world suddenly watching—weighed on her. “I don’t need to win another trophy to prove anything to myself,” she said. “I want to do this for them.” The sleepless nights and missed family events and days of perfecting their routine over and over. Again, she kept telling the team with a firm handclap. Again, again.

“I have a plan,” Aldama told me a few months later when she called out of the blue. Her voice had a girlish enthusiasm I hadn’t heard in our previous conversations. She was launching a jewelry business with Simianer, a breakout star from the first season. Aldama had been studying Kendra Scott, the designer who started her $1 billion business with a mere $500, working out of her Austin home. Aldama had been listening to the podcast Trading Secrets, hosted by entrepreneur Jason Tartick, then-fiancé of former Bachelorette star Kaitlyn Bristowe, whom Aldama met during her time on Dancing With the Stars.

Aldama had always dreamed of running a business, and it made perfect sense to align with the sweet-natured Simianer, who’d scored many product endorsements thanks to Cheer but was still searching for a career. Aldama proposed the partnership on the night she and Simianer presented an award at the Creative Arts Emmys, in Los Angeles. Simianer wore a red strapless dress sent by a designer, and Aldama wore a silver gown she’d bought in a panic at Macy’s. They clinked glasses that night, although Aldama doesn’t drink. One water glass gently kissing a flute of champagne to celebrate a new chapter.

But the next chapter would be entirely different.

Aldama was at a hair salon the afternoon of April 26, 2023, when someone in Navarro College’s human resources office called to tell her a civil lawsuit had just been filed by a former athlete, Madi Lane. The lawsuit named Aldama as a defendant, along with Navarro athletic director Michael Landers, Title IX coordinator Elizabeth Pillans, and a student named Salvatore Amico. Lane was a tumbler on the squad for a short time back in 2021. This was a year and a half later, so the time lag was odd, but Aldama remembered the incident. Lane had accused Amico, a male cheerleader, of sexual assault. In Aldama’s memory, they’d handled this one by the books. The Title IX office was alerted, and a police investigation ultimately led to no charges.

As she sat in the salon, a stylist’s hands working on the long locks Aldama

liked even if internet strangers did not, news of the lawsuit was metastasizing across social media, quotes from the court filing moving from Instagram comments to TMZ banners. “Keep quiet” was the quote most often attributed to her.

As the scandal made its way into headlines, Reddit users were tearing apart the finer points of the twenty-page court filing, trading alleged legal insight and insider backstories, though they mostly shared dismay. Awful. Disgusting.

“Sick to my stomach reading this,” wrote one user.

“They are f—ed f—ed, as they should be,” read one comment. “I hope this lawsuit brings down the whole program.”

When Aldama got home, she checked social media, and that’s when she knew this was bad, though she had no clue how bad it would get. Keep quiet. The line kept jumping out at her as she scrolled.

Madi Lane had arrived at Navarro in the summer of 2021, a tiny blonde with a squeaky voice. A couple of kids at Navarro made fun of that voice, but her tumbling spoke for itself. Navarro’s reputation had grown so much that its cheer team now recruited athletes from all over, even from other countries. One was a boy from Italy with a mop of dark curls. His name was Salvatore, though everyone called him Salvo.

College teams are tight-knit, but the Navarro cheer squad was tighter than most. Its members didn’t necessarily fit the jock mold—they were teacup-size girlie-girls and playful gay boys and straight dudes covered in tattoos. They tended not to mix with normie students, whom they call GP (for “general population”), and spent lots of their downtime together, most of them living in a pair of gender-separated dorms about fifty feet apart.

FIOFMU is the team’s unofficial motto. Aldama’s ladylike grandmother would be appalled to learn that, at least according to internet commentators, it stands for “Fight It Out, Fuck ’Em Up,” though her chain-smoking grandma would be proud. The civil lawsuit filed on Lane’s behalf, however, gave the phrase a sinister spin: “The letters were currency in a dark game where coaches and veterans bribed rookies to run errands, party, and perform sexual favors.”

Court documents can be rough reading, with their clunky civil codes and legalese, but parts of Lane’s filing rip along like a tabloid bombshell, with juicy asides about loosely related scandals. The details were building, however, to a theory that what happened to Lane was not an isolated incident.

“Defendants were aware of Navarro Cheer’s pervasive culture of sexual harassment, sexual violence, and intimidation,” the document states, “but rather than report abuse and hold perpetrators accountable, Defendants knowingly, intentionally, and with reckless disregard for the safety of others, turned a blind eye and decidedly failed to investigate and report allegations of misconduct. Navarro Cheer’s culture of sexual misconduct was promoted by intimidation and the power imbalance between coaches and cheerleaders and between veterans and rookies.”

Lane, according to the lawsuit, was taken aback by the hard partying at Navarro. She “abstained from engaging in this atmosphere,” according to this version; she had the highest GPA on the team. Her boyfriend attended Hill College, 45 minutes to the west in Hillsboro, and she visited him whenever she could. Her roommate, Emma DonVito, a fellow rookie, was dating a veteran cheerleader named Will Hernandez.

According to the lawsuit, Lane was sleeping in her dorm one Wednesday night after a quiet evening of study when DonVito returned from a party where she’d kissed Amico, the Italian cheerleader. It was late, but DonVito wanted to find Amico and bring him back to their dorm. Lane, aware that young women shouldn’t walk alone across campus after dark, accompanied her roommate to Amico’s dorm, but by the time the trio returned, DonVito’s boyfriend, Hernandez, was waiting outside. The quartet ventured inside, where things allegedly went awry.

From the lawsuit: “Salvo entered the bedroom and got on Plaintiff’s [Lane’s] bed. He began pulling off Plaintiff’s underwear and pants. Plaintiff screamed at Salvo to stop, and tried to keep him from removing her clothes, but Salvo continued. He pulled her shirt up and groped her chest and then inserted his fingers into her vagina. Plaintiff continued to scream at Salvo to stop. Eventually she was able to turn her body and push him away. She told him that he needed to leave, and he left the dorm.”

The following weekend exploded in drama. The lawsuit claimed that at a party that Friday, Lane was dressed down by a well-respected veteran cheerleader named Maddy Brum, who supposedly advised her not to tell Aldama. “Drink it off,” Brum is quoted as saying. “That’s what Navarro girls do—they drink. We don’t tell anyone.”

Brum is a cheer influencer with 450,000 followers on Instagram. Fans admire her work ethic, talent, and pint-size prettiness—the Natalie Portman next door—but she has her own hard-luck tale. In season two of Cheer, she revealed that her dad had gone to prison when she was around five years old. The court filing described Brum as dispatching male cheerleaders to trail Lane everywhere she went over the next few days and make sure she didn’t report anything.

What’s striking about the document is how few words are devoted to the

alleged sexual assault and how many are devoted to the lead-up and fallout. The lawsuit states that Lane’s boyfriend showed up on campus that Sunday with three friends, ostensibly looking for Amico, and discovered a male teammate, Stace Artigue, blocking the door to the room he shared with Amico. A tense confrontation ensued, and Artigue called the cops. The boyfriend received an assault complaint and was told by an officer to leave campus. Lane and her boyfriend were supposedly tailed by veteran cheerleaders brandishing guns and threatening to kill them for reporting the assault.

Where’s Aldama in all this? Much of the drama unfolded over Labor Day weekend, and she was on the banks of nearby Richland Chambers Reservoir with her Zeta Tau Alpha sorority sisters, a rare getaway. She says Lane texted her a vague “can you talk?” message, but Aldama asked if it could wait until Tuesday, and Lane agreed it could. After the controversy ignited on her phone later that weekend, Aldama says she did call Lane and they spoke briefly. According to the court filing, Aldama said, “Let’s not make this a big deal.” A few days later, when Lane met Aldama, having now quit the team, her coach told her, according to the lawsuit, “If you keep quiet, I’ll make sure you can cheer anywhere you want.” Aldama denies all of this.

Now, some eighteen months later, as the lawsuit punched its way into the clickable headlines of People and Us Weekly, Aldama’s Instagram was under siege. She turned off the comments then temporarily disabled the account. Amico, Brum, DonVito, and other students named in the document went into triage mode, blocking and deleting or turning off comments. They didn’t recognize Lane’s version of the tale. If those students could have, they likely would have shouted from the rafters: It didn’t happen like that. But it was team policy not to respond to online attacks.

Lane, meanwhile, stayed mum. Her most recent Instagram post was a photo

taken from the back so her face was partially obscured, blond mermaid curls spilling down her back. She was standing at a bookstore, pulling titles such as Bad Girl Reputation and Final Offer off the shelf. More than a hundred comments of support piled up, emojis of red hearts and prayer hands and a flexed yellow arm. “justice for u pretty girl,” said a typical comment.

The lawsuit landed on the internet nineteen days after the team’s 2023 triumph at Daytona, and Aldama spent the next five weeks in something like a comatose state. The spring semester had come to a close, and she cocooned in the family room watching TV. She became obsessed with Michael Jordan in The Last Dance. She binged Firefly Lane, a Netflix drama about two girls growing up in the seventies. She stayed on the couch so long her family grew worried. She stopped going to church. She stopped going outside much at all, though she did see a therapist. It helped. Her fingers went numb. Hives broke out across her back and chest.

Around her the storm of the civil suit was still knocking down power lines. The Cheer tour slated for that summer got scrapped. Her jewelry business with Simianer went belly-up—nine months of work down the drain. One day, shortly after the lawsuit hit, she says she got an official-sounding email that USA Cheer had placed her on a suspended list that would restrict any participation in cheer clinics and off-campus activity related to cheer, including Daytona. The legendary coach of Navarro, Monica Aldama, had practically been exiled from her sport—without any sort of hearing, on the basis of allegations that she stoutly denies.

Two months after the lawsuit was filed, I met Aldama in the entryway of a Tex-Mex restaurant in Ennis, halfway between Dallas and Corsicana. She looked shaken, wearing a blazer that probably once fit perfectly and now hung loosely on her small frame. I’d expected her to stop talking to me. Instead, she let me tag along to a meeting with her lawyer.

Russell Prince is a Florida attorney who specializes in due process violations in the world of athletics, an area of expertise that has earned him a robust roster of clients.

By the time we met, Aldama had been dropped as a defendant in the Lane lawsuit, along with Pillans and Landers. Lane’s legal representation had removed all three names in subsequent court filings after challenges from the Navarro defense team, but casual observers likely didn’t know this, because many of the outlets that tripped over themselves to pump salacious headlines onto the internet had not corrected the narrative.

Aldama had hired Prince to fight her USA Cheer suspension. Over baskets of tortilla chips, Prince expressed disbelief that USA Cheer hadn’t bothered to get Aldama’s perspective before issuing its edict. She says nobody asked her: Did this happen? Is this how you remember Madi Lane, the athlete with the “highest GPA on the team”? Aldama could have told them, for example, that Lane quit in September, two weeks into her freshman semester. She didn’t have a GPA.

USA Cheer had reduced the restrictions on Aldama after a hearing Prince described as a “shitshow,” but it would not remove them entirely, insisting on an independent investigation—but it hadn’t materialized. The governing body would almost certainly say it had acted so fast out of an abundance of caution, but how to explain the holdup?

The relationship between USA Cheer and Varsity has become the subject of much speculation. That the sport’s biggest business empire had direct ties to its governing body has left the company open to claims that it operates as a monopoly and with blatant conflicts of interest. Varsity has recently settled antitrust litigation and faces accusations of gross negligence stemming from the Rockstar Cheer scandal that ended in its founder’s suicide. (USA Cheer declined to be interviewed for this story, and Varsity did not respond to an interview request.)

As Prince talked and sipped from a red plastic cup of water, swatting at a stubborn fly that hovered near his face, Aldama fidgeted with her watch, its black analog face rimmed with crystals. She had been silent for much of the hour, but now she sat forward. Referring to Lane, she said, “I want people to know she lied.” She smacked the table. “That there’s evidence,” she said, another smack. “That cameras show she made a false statement to the police.” Smack, smack.

Once upon a time, stories like Lane’s were often disbelieved. Young women who felt sexually violated faced a court system and a culture that showed little interest in the harm they reported. But that is changing. Thirteen years ago Title IX enforcement began to ramp up on college campuses, alerted by the Obama administration that they had to start taking sexual offenses seriously or else lose federal funding. It’s been more than six years since the Me Too movement introduced the mantra “Believe women.” But which women? Under which circumstances? In many circles, and often in the public forum, questioning any sexual assault allegation can be seen as essentially taboo.

Months of muzzling herself online and in person had left Aldama ready to burst. She fantasized aloud about arriving at an upcoming SMU camp, her first public appearance since the scandal, wearing a shirt emblazoned with the words “LIES LIES LIES.”

Prince laughed but then grew serious. “Don’t do that,” he said.

Prince estimated that 80 percent of the defendants he represents have faced allegations not made in good faith, though he later clarified that the vast majority of these are not cases of sexual violation so much as emotional and physical abuse. Of course, this number must be sifted through the filter of his legal specialty. In his observation, the accusations often came from athletes who were promised golden futures that never materialized. They needed to blame someone, anyone. The stories were so rich and complicated, he said, they’d make a very good Netflix series. He joked that maybe Cheer could come back for another installment. “This is actually a show I would watch!” he said, and Aldama put out both hands at the idea. But she was laughing.

A female coach with Aldama’s principles and courage would be the right voice to ask these questions, Prince told her. “You are the perfect person to make substantive changes in your sport,” he said. Monica only sighed, and Prince said, “I know this isn’t the kind you had in mind.”

The evidence Aldama had been referring to when she smacked the table lived in a hefty police report made in the days following the incident. The report is 21 pages, and it reads like one of those multicharacter novels in which no one experiences an event the same way. The tone is less Jonathan Franzen, more “just the facts, ma’am,” but the takeaway is the same: we are all unreliable narrators in our own story.

Sexual assault allegations often come down to a “he said, she said” narrative. For that matter, so do fights between friends, married couples, and family members. Who can know what happens between two people behind closed doors? But this sexual assault allegation was unusual because there were two witnesses.

It was September 2021, the start of school. Lane and her roommate DonVito shared a dorm room that was typical for college: intimate enough to induce claustrophobia. A banner that read “Babe Cave” hung on the wall. The room had twin beds against either wall, and on the night of the incident, according to their accounts to police, DonVito and her boyfriend, Hernandez, cuddled in one. Lane slipped under a blanket in the other, and eventually, DonVito said, so did Amico. Then, in that curious way of dorm rooms, the two pairs simply started doing their own thing.

What happened between Amico and Lane—wanted or unwanted, mutual or predatory—is a matter for the court. What DonVito and Hernandez insist is that Lane did not scream, as her court filing claimed. They would have heard that. The room was small enough to hear a whisper.

The police report revealed other discrepancies. Lane told an officer that she and DonVito walked to Amico’s dorm to get him at around 4 a.m., but surveillance cameras clocked them at 1:47 a.m. While Lane’s version placed Hernandez outside their dorm when they returned with Amico, camera footage snapped him at the building before the roommates ever departed. According to Hernandez and DonVito, the three of them had been hanging out for a while. DonVito insisted it wasn’t her idea to get Amico; it was Lane’s.

And though Lane’s court filing depicted her as appalled by the hedonism she witnessed at Navarro College, DonVito remembers Lane as the one who was messed up that day. Lane returned from seeing her boyfriend at his college in Hillsboro that afternoon and told DonVito she’d taken four pot gummies. The roomies went to Walmart to buy munchies. Before leaving the dorm, DonVito shot a video on her phone: Lane is pulling back her long hair at the sink, asking teammate Stace Artigue to help her vomit. Artigue, a handsome and street-smart rookie from Baton Rouge, slips two fingers down her throat, but Lane only gags, collapsing into laughter. All three are laughing.

One detail of the court filing few Navarro team members dispute is the “hard-partying atmosphere.” In this, Navarro is no different from most colleges, but that September 2021, fresh from summer vacation and still shaking off the pandemic, the partying may have been harder than usual. Not everyone on the team was reckless; a lot of cheerleaders don’t even drink. But Aldama would kick three athletes off the team in October, mostly for smoking weed. Aldama submits her athletes to random drug tests, and she has a zero tolerance policy. But risk-taking is a necessary part of growing up—and of cheerleading, for that matter—so parties happened anyway.

I reached out to Lane for this story, and she politely directed me to her lawyer, Jud Waltman, a personal injury attorney at the powerful Lanier Law Firm, in Houston. I repeatedly called Waltman, but he never called back.

Amico, for his part, has consistently denied her version of the incident. He says their encounter was consensual.

Aldama learned that Lane was withdrawing from school when she arrived at Navarro on the Tuesday after Labor Day. She met Lane in her office that night. The young woman’s mother and boyfriend stood nearby as Lane handed in her black-and-red uniform. There was a hug. It was awkward. Good luck, that kind of thing. What Aldama categorically denies ever saying is this: “If you keep quiet, I’ll make sure you can cheer anywhere you want.”

“Let’s look at that statement,” Aldama told me one afternoon as we sat in her office. “I have no power to get her on any team she wants. I would never try to have anybody cover up a sexual assault. And those two things together? Are insane.”

Not to mention that police got involved on Sunday, two days before Lane had gone to her office to turn in her uniform. I contacted Lane’s mother to see what she recalled of that conversation, but she directed me to the same lawyer who didn’t respond.

Lane went on to cheer for the University of Texas Permian Basin, where her mother coached. She tried out for the Texas Tech University team but didn’t make the cut, a decision used in the court filing as evidence of blackballing, although Aldama says she only learned that Lane had tried out for the squad after a mutual acquaintance told her she didn’t make it. Other students involved that night, fresh-faced rookies when the incident took place, were seasoned veterans by the time the lawsuit hit in April 2023. DonVito was FaceTiming with her mom on her bed when someone texted her a link to the court filing, which had been posted on social media. She clicked to a document and scanned it with mounting dread.

Artigue came to her dorm, and the two sat on her floor. Her phone was blowing up. Are you okay? Her friends, her mom, the team. The story was everywhere. She was not okay—and would not be for a while.

When the Navarro Bulldogs won Daytona in early April 2023, their sixteenth national championship, Aldama had splashed into the placid Atlantic along with the rest of the team. The run into the waves is the traditional victory celebration at Daytona. She embraced her Bulldogs and hooted with joy as her long hair grew wet and stringy. In a photo, she knelt on the sand holding the trophy with her assistant coach Dustin Velazquez.

She’d recruited Velazquez, a former Navarro cheerleader, to help lead the squad two years earlier. He’d been a manager at Disneyland when COVID hit, and he found himself among the newly unemployed. He was punching in at UPS when his old coach called him up. “I think she likes me because I’m a square,” he told me. When I shared this with Aldama, she clapped and said, “That’s right!”

The lawsuit landed about two weeks after the team returned to Corsicana. Aldama was dismissed as a defendant within weeks, and her restrictions had been eased within two months, but it would take four more months for USA Cheer to remove Aldama from the suspended list entirely, in November 2023, after an investigation that she says wrapped in a matter of days. She posted about her release shortly after. “I am just finding my voice today,” she wrote on Instagram, in a note that unfolded over seven slides. She summarized her long season of sadness, expressed dismay and anger over USA Cheer’s mysterious delay in clearing her of suspicion, and wondered how the industry could balance the protection of athletes with the support coaches need.

The comments filled with heart emojis. “love you queen” one former athlete said. (Actually, several did.) “We always knew!!!” said another.

That December, right before Christmas, Aldama gathered her team in the Navarro gym and told them she was retiring. Twenty-nine years was a good run. She’d planned to do it before the lawsuit had been filed, but she refused to leave until she’d been cleared by USA Cheer. That would have been an admission of defeat.

The kids didn’t want to see her go. “I’ll be around,” she told them, a promise and a warning. She held it together until her family emerged from an adjacent room where they’d been secretly stashed. Surprise! Aldama had sacrificed a lot of time with her family to shepherd the program. Whatever was driving her in those years—ambition, the need to show athletes what they were capable of, to prove what she was capable of—had a cost. Everything worth doing does.

The legal battle wasn’t over for Salvatore Amico, whose name was the last one on the lawsuit with Navarro College. It wasn’t clear whether the NCA would allow him to compete at Daytona. Aldama was still trying to get clarity on that, but ultimately he had to sit it out.

I met her one last time in that office with the red wall. “Sorry it’s a mess,” she told me, but it looked the same: plastic bins filled with uniforms shoved to the side, unhung posters leaning against the wall, the long rectangle of butcher paper over the fluorescent light, one corner flap peeling away under the tug of gravity. She looked freer and happier than I’d ever seen her.

“I just accepted a job offer,” she told me. “So much for retirement!” She would be a vice president at a North Texas–based cheer company. She got the high-powered executive gig she’d always wanted but kept her Corsicana address.

I asked Aldama, once more, if she would have participated in the Cheer docuseries if she’d known about the fame that would flow from it and where that fame might lead.

“Wow,” she said, taking a beat. She did Cheer because she hoped to educate the world about the sport. What she didn’t anticipate was that she would get an education too. She was naive; she knows that now. She never could have imagined how ugly some people can be. Without Cheer, so many of the kids wouldn’t have had these incredible opportunities. But without Cheer, Aldama doubted that Lane’s lawsuit would have ever been filed. Fame had flung open new horizons and slapped a target on Aldama’s back.

To be a woman of faith is to believe that whatever challenges you face, whatever pain and anxiety you walk through, has a purpose. “Maybe my voice is to be a voice for the wrongfully accused,” she said, though she didn’t sound convinced. “I’ve had a lot of people reach out to me, like, thank you for speaking out. I don’t really know what my calling is, but I’m listening, and I’m going to follow my heart.”

I wanted to leave Coach Monica there, in the snug but uncertain place of her fresh start. She’d stuck her landing. But happy endings are the stuff of art.

On January 22, 2024, another headline hit TMZ: “ ‘CHEER’ STAR MONICA ALDAMA SON AUSTIN CHARGED WITH CHILD PORN.”

Austin had been indicted by a grand jury in Corsicana on charges of possessing child pornography that dated back to July 2022, when he was 25.

TMZ broke the news about Austin a few days after he’d surrendered himself on an open warrant to the Corsicana justice of the peace, where he was booked in county jail and released on bond. The site’s main photo was a close-up of Aldama with an inset of her son’s unsmiling mugshot.

The Aldamas learned of the case not long after it was opened, when they were notified by the Texas attorney general’s office, which did not respond to an interview request. It’s not uncommon for the AG’s office to handle these kinds of cases in small towns, whose law enforcement may not have the necessary resources, but it was still a mystery what exactly law enforcement had found and how it had been discovered. A warrant to search the Aldamas’ home was executed in July 2022, when two men showed up at the door, one wearing the suit of an investigator. Austin’s room was searched, his computer taken. After the men left, the Aldamas noticed Austin’s phone was still there. They called the investigator to ask if he wanted it. He did.

Cases involving sexually explicit photos and videos of children rarely go to trial. Most defendants want such charges to disappear, and juries are notoriously unsympathetic. When I called Austin’s lawyers, however, they insisted they were eager to prove Austin’s innocence in court. “We’re ready to fight like hell,” said Heather Barbieri, a Dallas-based attorney who’d joined forces with Corsicana lawyer Kerri Donica, a friend of the Aldamas from way back.

Once again Monica Aldama had been thrust into the role of defending someone accused of a crime deemed indefensible. Austin’s mug shot made its way onto gossip rags and a Portuguese-language publication. But this time it wasn’t a surrogate son she was defending; it was her son. And this time it wasn’t random strangers on Twitter condemning her; the critics included some of her neighbors in her hometown.

Aldama didn’t want to talk about the case, but she took my call anyway. She insists that the charges stem from Austin mistakenly clicking on a single link, years ago. “That’s my child,” she said in a small voice. “I’ll take all the pain. Just don’t talk about my child.” When she started crying, I shut my laptop and stopped taking notes.

I had to wonder: how many scandals can erupt on one team? While reporting this story over the course of eighteen months, I was torn between thinking Aldama had the worst luck in the world and wondering, on the other hand, whether there was indeed something rotten in Corsicana. Was sexual misbehavior more common here or just more visible thanks to the scrutiny brought by the Netflix fame? Internet commentators kept insisting that Aldama could have done more to prevent these scandals. But from where I was standing, she looked like a convenient, high-profile scapegoat. None of us really knows, though. The internet promised us only information—never the truth.

Aldama and I arranged a phone chat one Sunday morning to clarify a point about Austin. I’d never heard her voice so cracked by pain. She didn’t understand why her son wasn’t off-limits. She didn’t understand how this had become the coda to her 29-year career. She didn’t sound angry; she sounded pushed beyond reason—by the long streak of scandals, by the online vultures that will peck at any carcass, by gossip rags that will report allegations against you without seeking your side of the story.

“I’m just really tired of being everybody’s entertainment,” she told me, and she began crying again, but I kept taking notes this time.

Something that Stace Artigue told me kept floating back to mind. “I think cheerleaders are broken individuals,” he said as we sat in Aldama’s office. “They join cheerleading because there’s structure. There’s responsibility, a lot of admiration.” He gestured to the red wall, decorated with framed photos of kids in triumphant poses. “A lot of cheerleaders on this wall, they’re broken somewhere. They got told no, and cheerleading was their yes.”

The Cheer mythology—good kids, feel-good stories—might be as oversimplified a story as the one in which they are part of an evil cult. The truth lies somewhere in between, same as it ever has. These are troubled kids and amazing young athletes. We are all broken people if you look closely enough. If we’re lucky, we find a way to be healed.

I watched practice once. The loudspeakers were blaring a hip-hop song I didn’t recognize as kids laughed and danced in the downtime between attempts at a pyramid formation. Aldama stood to the side in snug black jeans and black boots, chewing gum but otherwise remaining silent, surveying the landscape.

A pyramid is a marvel of the human body’s potential, one person thrown into the air only to be caught by hands and shoulders, a defiance of gravity. The structure crumbled at one point, and I gasped. Aldama told me the Cheer crew had the same reaction at first. But you get used to it. Kids fall. Kids get up. You just keep trying.

When they finally nailed the formation, I couldn’t help myself. I cheered.

This article originally appeared in the May 2024 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “What Cheer Led To” Subscribe today.

video: Inside the story

Writer Sarah Hepola reflects on the reporting of this story.

- More About:

- Sports

- Film & TV

- Television

- Longreads

- Corsicana