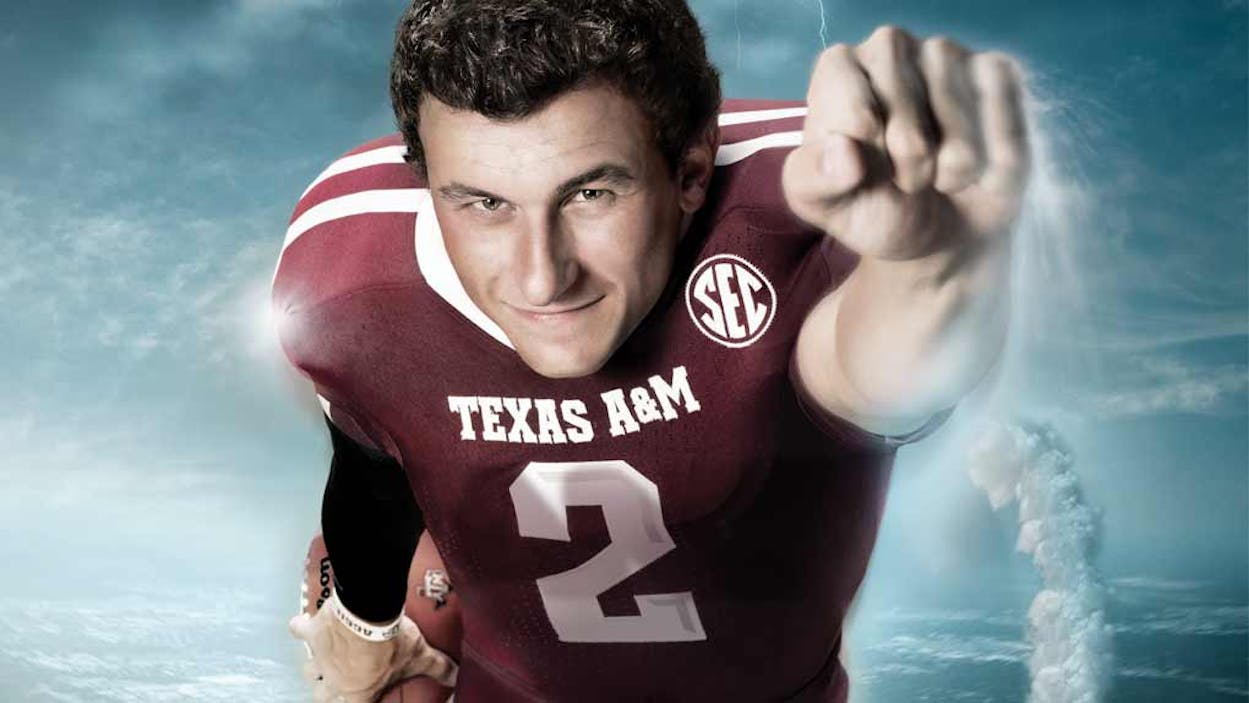

By nine p.m. Eastern Standard Time on the second Saturday in December last year, we knew exactly who would be on the cover this September. That was the night that Johnny Manziel became the first freshman ever to win the Heisman Trophy. As soon as the holidays were over, we began to set in motion the process that led to our September cover story, by S. C. Gwynne (the story, “Who Is Johnny Football?” will be online later this week and on newsstands next week). This was as no-brainer an editorial decision as they come. Manziel—a fourth-generation Texan, raised in Tyler and Kerrville, playing quarterback for Texas A&M—was straight out of central casting. He’d almost single-handedly carried the Aggies into the national spotlight, which they had been striving for so long to reach. The concept for the cover was simple: he was the Aggies’ Superman. We called contributing photographer Randal Ford (himself an A&M grad) and told him to start researching poses for the Man of Steel.

Almost immediately, however, the story began to shift, as Manziel’s tumultuous off-season generated wave after wave of (mostly negative) publicity. By summer, pretty much every sportswriter in the country had weighed in, most of them scolding Manziel for failing to realize that he was not simply a twenty-year-old football player but actually a character in a morality play. Manziel, it quickly became apparent, is the kind of reckless celebrity America loves to obsess over, Lindsay Lohan in pads. In a matter of months, he had achieved a dubious renown, culminating in the dramatic news that the NCAA was investigating him for receiving money for autographing souvenirs to be sold on the memorabilia market. Like most Manziel stories, this one exploded, despite the fact that, at the outset, there was no hard evidence of the alleged violation (at the time our September issue went to press, this was still the case). But as Sam’s story smartly points out, this viral quality is part of Manziel’s special power: stories about his off-field exploits are as unstoppable as he himself is on the field. He has a knack for getting into trouble and narrowly escaping, only to find himself in another fix, which he somehow wriggles out of, only to get tangled up again, and so on. His greatest strength is also his greatest weakness.

Which is to say, he’s still a kind of superhero, even after all this. It’s just that, like most modern superhero stories (Man of Steel, The Dark Knight, Hulk), the saga of Johnny Football has ominous overtones—the hero himself is far from perfect and the world he lives in is hopelessly corrupt. Does anyone still believe that college football—a business valued at more than $1.2 billion per year—is truly an amateur sport? Or that it’s fair for the players—who are largely if not entirely responsible for creating that revenue, and for whom, in an increasingly dangerous game, there is no guarantee of future NFL income—to receive nothing more than free tuition for a degree that many won’t even stick around long enough to complete? (Senior editor Jason Cohen doesn’t.) No, Manziel is not the paragon of idealistic virtue represented by the original DC Comics Superman. That character, with his Boy Scout morality and regal bearing, belonged to a simpler era. Johnny Football is something far more interesting: the brilliant but catastrophic superhero our decadent world deserves.