Heather Simpson dressed up as measles for Halloween in 2019 because it was, as she told her growing following on social media, the “least scary thing I could think of.” The Dallas mom was then a full-fledged anti-vaccine influencer, drawing tens of thousands of likes and comments on her Facebook posts that denied the safety and necessity of childhood vaccinations.

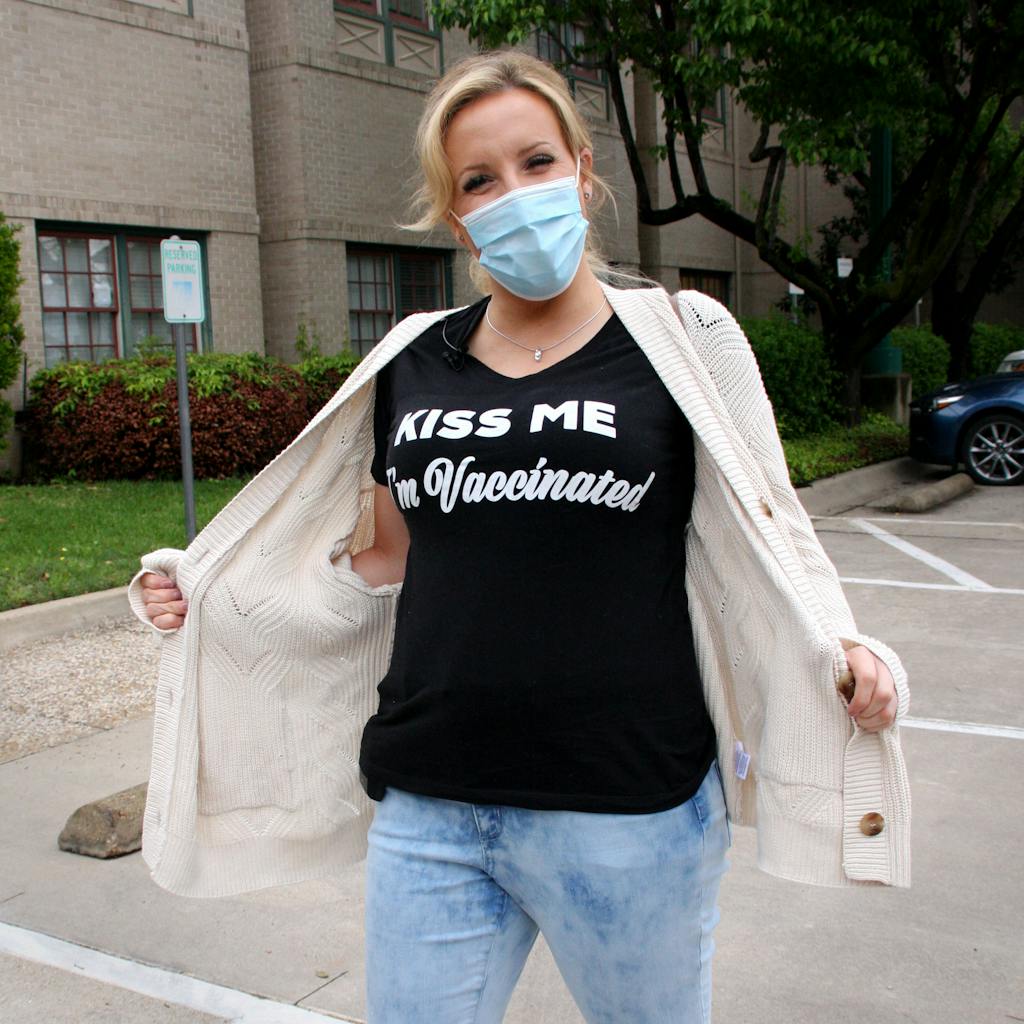

But today most of the thousands who recirculated those posts have abandoned and shunned her. On a mid-April afternoon, Simpson battled traffic into downtown Dallas to reach Baylor University Medical Center for her first dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine against COVID-19. Clad in jeans and a black “Kiss Me I’m Vaccinated” T-shirt—and a mask—the upbeat thirty-year-old said she wouldn’t back out, despite her anxiety.

“I’m freaking out. I hate needles. I’m gonna pass out,” she said. “But I trust the science.” The day before, she’d taken her three-year-old daughter to receive her first-ever vaccine, against polio. Now it was her turn. “I am now a full believer in vaccines, and I believe that the COVID vaccine is the way that we’re going to end the pandemic,” she said.

Simpson’s journey, from falling into the world of anti-vaccine activism to finding her way out and even to promoting vaccination herself, reveals not only how easily the movement entraps people but also that it’s possible—if much harder—for minds to change. The way Simpson was hooked and what she came to believe highlight the kind of insidious misinformation that has hampered the nation’s response to the pandemic, fueled hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccines, and undermined the efforts of public health officials.

Simpson wasn’t always anti-vaccine. She grew up receiving all her recommended shots, and until her daughter was born, the only inoculation she had refused was the meningitis B vaccine before starting college—and then only because she hated needles. But in 2015, after she and her husband had begun trying to conceive, she went online to learn more about the immunizations recommended for children.

“We thought, ‘What should we do? Should we just go with it?’ ” Simpson recalls. The next day, a Facebook ad led her to a nine-hour self-described documentary on the “truth” about vaccines produced by Ty and Charlene Bollinger, a hugely influential couple in the world of alternative medicine and anti-vaccine activism. Ty Bollinger, a former bodybuilder with no medical background, and his wife profit from books and videos promoting fake cancer cures, disinformation about vaccines, and, most recently, false claims about COVID-19. “We ended up watching all nine hours, and they basically blame every bad thing under the sun on vaccines,” Simpson says. “To be honest, any person that’s prone to fear, any new parent watching it, is going to have a hard time not falling for it, and I fell for it.” Most convincing were the half-dozen anti-vaccine doctors who claimed that vaccines are harmful.

Simpson’s biggest fear was that vaccines could cause sudden infant death syndrome, but she also worried about autism, cancer, or brain damage from aluminum contained in them. Research has conclusively shown that vaccines do not cause SIDS, autism, or cancer, and though some vaccines do have a small amount of aluminum, it does not cause harm.

When her daughter was born two years later, Simpson and her husband skipped all of the recommended inoculations. Yet it wasn’t until her daughter was a toddler that Simpson first took her uneasiness about vaccines to social media, with a public post on her Facebook account in February 2019.

“It wasn’t even super anti-vax, but it got shared hundreds of times, and I got all these friend requests,” she says. A community of anti-vaccine moms had embraced her, and she was on the radar of pro-vaccine advocates too. More than a dozen Facebook pages popped up attacking Simpson. She would wake up in the middle of the night shaking from the vitriol directed at her. “No one really coaches you on how to handle five thousand hate comments,” she says. The “pro-vax” rancor also solidified her resolve—to an extent. “I thought the hate must mean I’m doing something right,” she says.

Simpson is far from the only Texas mom to be taken in by anti-vaccine disinformation, despite an overwhelming body of scientific evidence demonstrating that vaccines are safe and effective. Two leaders of the international anti-vaccine movement have even made Texas their home. Andrew Wakefield, the discredited English gastroenterologist who published a fraudulent study linking vaccines to autism, owned a home in Austin for more than a decade until his recent divorce left it with his ex-wife, and Del Bigtree, an anti-vaccine filmmaker, moved to Spicewood in 2019.

Though the state’s anti-vaccine movement began small in the 2000s, it was born again in 2015 after a state legislator introduced a bill (never passed) to remove all exemptions for school immunization requirements that weren’t based on medical reasons. A new brand of more politically savvy anti-vaccine advocates emerged and formed the first statewide anti-vaccine political action committee, Texans for Vaccine Choice.

It’s difficult to track the movement’s influence over time, but the state tracks the immunization exemptions it grants. In 2003, when legislation made it easier to obtain them, the state had only 2,300 nonmedical exemptions. Today more than 2 percent (nearly 7,700) of the state’s kindergartners start school without having received all their required vaccines, and Texas has granted more than 72,000 exemptions for K–12 students. Not all parents seeking exemptions for students, however, are “anti-vaxxers.” Some may skip a single vaccine. Others are delaying vaccines or simply haven’t had time to get them. It’s difficult to pin down how many people make up the core anti-vaccine movement in Texas, but experts agree the group is small.

“It’s a tiny part of our population with a hugely outsized voice because they’re loud and mean and aggressive,” says Lacy Waller, an organizer with Immunize Texas, a grassroots vaccine advocacy group. “It’s a lot of coordination to make the movement seem loud.”

That coordination grew during the pandemic as anti-vaccine advocates joined forces with “anti-maskers,” anti-lockdown advocates, and gun rights groups. The expansion of anti-vaccine sentiment from childhood immunizations to the COVID-19 vaccine worries public health experts.

“We have to recognize that the reason half a million Americans lost their lives from COVID-19 was partly because of the SARS coronavirus type 2, but it was compounded by the deliberate defiance of masks and social distancing and now vaccines,” says Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine and codirector of the Texas Children Hospital’s Center for Vaccine Development at the Baylor College of Medicine, who’s been fighting the anti-vaccine movement since moving to Texas in 2011. “Anti-science disinformation is a killer.”

Vaccines became available to all Texans age sixteen and older at the end of March, but less than half of those eligible (48 percent) have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, and just one in three (33 percent) has been fully vaccinated. Though rates are higher among those 65 and older—75 percent have received at least one dose, and 62 percent are fully vaccinated—the CDC director recently warned that young people have begun driving infections. Demand for vaccinations has begun to drop in Texas. The state also lags nationally in COVID-19 vaccine distribution, ranking thirty-seventh in the percentage of administered vaccines (74 percent).

Though it’s difficult to measure the broader role of anti-vaccination activists in contributing to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, “they are definitely sowing seeds of doubt,” says Rekha Lakshmanan, director of advocacy and policy for the Immunization Partnership, a Houston-based nonprofit focused on community education and legislative policy. “I don’t think it originates with them, but I think they’re stoking it, adding tinder to the fire to keep it going.”

Simpson saw this play out in her Facebook feed, where anti-vaccine friends also expressed opposition to wearing masks to reduce COVID-19 transmission and touted conspiracy theories about the origin of the pandemic. Several events had nudged her away from her anti-vax leanings. When she became anxious about tetanus after her daughter was scratched by a cat, her pediatrician reminded her that the tetanus shot could remove that worry. When she told friends she had an upcoming surgery, her anti-vaccine friends urged her to skip pain medication or forgo the surgery altogether, saying a healthy lifestyle solved any medical issue—a claim Simpson questioned. Then, a week before her surgery—a year after her initial anti-vaccine post—Simpson wrote on Facebook that she didn’t want “to abolish vaccines, just to make them safer, because I know at some point at least one vaccine somewhere has saved one life.

“The anti-vaxxers just lost it on me,” she recalls. “I ended up in the ER with a panic attack, and that was the beginning of the end.” Over the pandemic summer, Simpson sought out pro-vaccine books and experts to educate herself. She posted pro-mask comments on Facebook and watched her anti-vaccine friends disappear.

“Having been an anti-vaxxer, I understand what they’re thinking and why they think that way,” Simpson said just before stepping into the Baylor hospital in April to receive the vaccine. “I feel like I’m able to help parents who are on the fence because I can relate and empathize. I can say, ‘I’ve been there, and this is why I’ve changed, and this is why you don’t have to be afraid.’ ”

Once inside the hospital, Simpson filled out the vaccine paperwork and then followed a nurse through a circuitous hallway to a private room. Inside, two nurses sat at either side of a table in front of a white backdrop patterned with the hospital’s logo and a syringe above the words “Vaccinated Against Covid-19.”

Simpson prepared herself, setting a bottle of water beside her and digging out of her purse the lollipop she had swiped at the pediatrician’s office the day before, when her daughter got vaccinated against polio. Then she took a deep breath as the needle went in.

“I feel great,” she said afterward. “I thought I would get light-headed, but I really didn’t.”

She did, however, end up at the ER that night with a severe headache and itchiness all over. The staff told her she was having a reaction to the vaccine and gave her Benadryl through an IV along with some pain medication.

Would she do it all over again? Will she get the second shot? Yes and yes. She’s young and healthy, but she doesn’t want to risk passing COVID-19 on to someone else or take even the tiniest risk of leaving her daughter motherless.

“It’s nice to know that I’m going to be protected against COVID,” she says. “This is the way to end this pandemic, and I’m glad to be able to do my part.”