Like so many of Dr. Irene Stafford’s impoverished and unhoused patients, the twentysomething woman showed up, in labor, at the Houston hospital having received no formal prenatal care. Stafford, a maternal and fetal medicine specialist, leaped into action and safely delivered the baby.

As required by Texas law, the young woman was tested for syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease that can prove deadly to the mother and can spread to the fetus in the womb if untreated. The test results were positive, but by the time the doctors received them—many hours later—the new mother and her infant had been discharged.

Stafford called the phone number provided by the patient, whom she refers to as Miss Jones to maintain her privacy. The woman who answered introduced herself as Miss Jones’s mother and explained that her daughter was back on the streets, with no means of being reached, but Miss Jones’s two children were there.

If Stafford couldn’t treat the mother, at least she could treat the newborn. “I care about your daughter, and I really care about these babies,” she said.

The grandmother didn’t require any further explanation. “I know the baby has syphilis,” she said. “So did her first child.”

Despite Stafford’s diligence in quickly delivering care to the children, the syphilis bacterium had already done significant damage. If Miss Jones had received treatment during her pregnancy, she and her babies could have been cured, with little or no lasting harm. Instead, five years later, the children continue to face severe symptoms, including neurodevelopmental problems. The oldest remains unable to speak or eat, relying on a feeding tube for nutrition.

Annual cases of congenital syphilis in the U.S. have increased tenfold since 2012, to more than 3,700. Texas has the highest number in the country, accounting for almost 25 percent of the nationwide total in 2022. Only New Mexico, South Dakota, and Arizona saw a higher proportion of cases. If Texas is the epicenter of congenital syphilis, then Houston is the epicenter of that epicenter. Last July the Houston Health Department alerted the public to an outbreak, noting an 844 percent rise in congenital syphilis cases between 2016 and 2021. For comparison, there was a 183 percent increase nationwide between 2018 and 2022.

The disease can often be cured with a single dose of injectable penicillin, but only if doctors can diagnose it. Stafford had long been frustrated by the disconnect between the ease of curing syphilis and the challenges of getting many patients diagnosed and treated. Those at highest risk of contracting syphilis—the poor, the unhoused, the uninsured, undocumented immigrants, and those struggling with addiction and mental health disorders—are also facing the biggest hurdles to obtaining timely medical care. Daily, it seemed, Stafford’s office received last-minute calls from patients canceling appointments because they didn’t have a babysitter, access to a car, or permission to miss work.

There had to be a better way, Stafford thought, which led to a eureka moment in early 2023. If she could create a dedicated clinic for treating congenital syphilis, she could help both the mothers and their children. She could provide prenatal care, ensure that they received testing and treatment, and connect families with vital social services. Through working with these families, Stafford could also sketch a clearer picture of how congenital syphilis affects long-term health.

Stafford launched her syphilis program last June at the UT Physicians Obstetrics and Gynecology Continuity Clinic within Houston’s sprawling Texas Medical Center, and in September she won a $3.3 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to fund her efforts.

Syphilis is an old disease. It first began ravaging Europe in the late fifteenth century, killing rich and poor alike as it spread between sex partners and from mothers to children. It remained untreatable—wreaking havoc upon brains, bones, joints, and skin—until the mid-twentieth century, after the discovery of penicillin. Even after the advent of a cure, the disease has remained stubbornly persistent. It’s caused by a corkscrew-shaped bacterium known as Treponema pallidum that, left untreated, replicates and persists in a body for decades.

Syphilis in adults usually causes only mild symptoms at first. The classic syphilis chancre, an open sore on the genitals or mouth, is often small and painless. Many who are infected don’t even notice it, and it disappears without treatment. Secondary syphilis, which appears several months after the initial chancre, causes a rash on the hands and feet, as well as headaches, fatigue, and fever. Such symptoms, common to any number of diseases, give syphilis its nickname: the “great imitator.” As a result, many patients don’t know they have syphilis or that they can transmit it to others.

Syphilis cases hit a nadir in 2000—fewer than six thousand cases nationwide—thanks to an aggressive elimination campaign led by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But funding for syphilis testing and contact tracing was slashed as cases fell. It didn’t take long for numbers to rise again, an increase that became a surge in 2012. Epidemiologists have found an

association between the spread of syphilis and rates of heroin use, meaning the nation’s opioid crisis may have contributed to the pronounced rise in syphilis cases. Other at-risk groups include gay men and those who are HIV positive. Public health officials have also had to contend with the stigma surrounding syphilis—which may make patients less likely to share their sexual histories with physicians—as well as with a deprioritizing of government funds that address the problem.

“Syphilis doesn’t have the—I hate to say the word—the ‘glamour’ of other types of diseases,” says Pablo Sanchez, a pediatric infectious-disease physician at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, in Ohio. Big public campaigns exist to fight breast cancer and heart disease, but “we don’t have syphilis awareness month. It’s not something people want others knowing about, so it remains a hidden epidemic.”

Just as in adults, syphilis in a fetus can be difficult to diagnose. While some of those infected show signs of its effects in the womb, others appear perfectly normal for weeks, or even years, after birth. A January 2024 report from the CDC revealed a 30 percent jump in congenital syphilis cases between 2021 and 2022 alone. Yet many physicians remain unaware of the scope of the problem. “For many of us, we were trained in a time when syphilis was something you read about in a textbook. It seemed like ancient history. And to suddenly be confronted with it in practice, you may miss it,” says Judy Levison, a recently retired professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine, in Houston.

Unsurprisingly, with the highest rate of uninsured residents in the U.S., Texas in particular is grappling with the syphilis surge. The situation can be especially challenging for immigrants lacking permanent legal status, who often can’t access prenatal care because of language barriers and a lack of health insurance. Instead they tend to show up at emergency rooms during labor. “Our health-care system is not very welcoming to people,” Levison says. “The system’s broken.”

Although Texas passed a law in 2019 requiring that all pregnant women be tested for syphilis three times (during the first prenatal examination, the third trimester, and at delivery), not all physicians are aware of the rule, Stafford says. Data showing the impact of this law on rates of syphilis testing during pregnancy aren’t readily available, and the legislation is of limited benefit to Texans who lack access to routine prenatal care. Even if uninsured pregnant women seek care at an emergency room and get tested, as Miss Jones was, the results may not be available until after a patient has been discharged.

Overtaxed physicians must then track down such patients, many of whom may be difficult to reach because they are unhoused or living in the country illegally. Even if a search is successful, many of these patients can’t always arrange for transportation or time off work to get treatment—if they have a means of paying for it at all. Such situations help explain why the Texas Department of State Health Services found that only 26 percent of women who delivered an infant with congenital syphilis in 2022 received timely, adequate treatment.

Without receiving such treatment during a pregnancy, some 40 percent of offspring conceived by syphilis-infected mothers will die during gestation or in the first months of life. Others are born prematurely or suffer a blistering rash, distended abdomen, and misshapen bones at birth. Even then, it’s not always clear syphilis is the cause. Other babies with syphilis appear outwardly healthy, with only a mild rash on the hands and feet or no symptoms at all. They can slip through the cracks without adequate testing. If syphilis isn’t diagnosed until after birth, the infection can be cured, but the bacterium may have already caused neurodevelopmental delays or permanent damage to the bones or liver. Stafford was shocked as a young physician by how little many medical professionals knew about how to help these children.

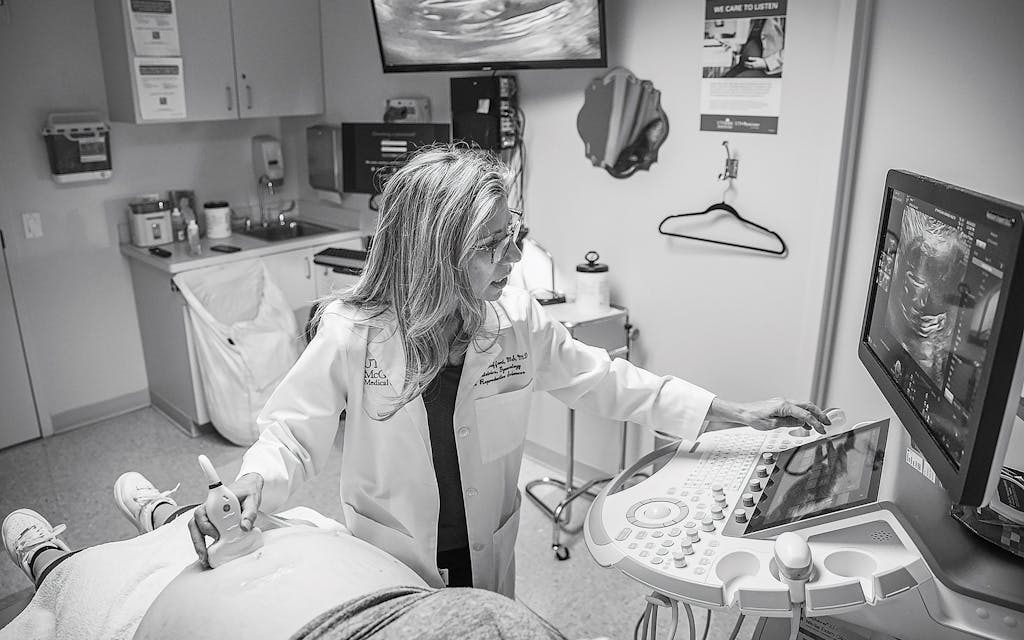

After applying a spurt of conductive gel to a pregnant woman’s abdomen, Dr. Edgar Hernandez-Andrade places a wand against it and begins an ultrasound examination. Such screenings during pregnancy are routine, but what Hernandez-Andrade is looking for shouldn’t be. To an untrained eye, the grainy black-and-white flickers that appear on the screen resemble white noise. But Hernandez-Andrade, a physician who specializes in prenatal imaging, can pick out details in a developing fetus that elude even other trained professionals. The pixelated image reveals an abnormally large placenta, liver, and spleen in the mother, as well as stunted fetal growth. Together they’re common signs of fetal syphilis.

Hernandez-Andrade can’t predict how the woman and her partner will respond when he breaks the news. Some parents he’s dealt with don’t immediately understand the harm syphilis can cause and so seem unconcerned. Other times, they’re terrified. Hernandez-Andrade sees expectant parents with suspected or confirmed syphilis at Stafford’s clinic, which has treated roughly seventy patients since it opened. The clinic plans to follow each parent and their children for more than a year to better understand the progress of the disease. Such research is scarce in the existing medical literature.

Stafford’s efforts have been helped by a March 2024 state Medicaid rule change that extends health coverage to qualifying mothers for as long as twelve months after the birth of a child. The clinic provides a full range of services to parents, ranging from transportation and childcare to housing assistance and behavioral health appointments.

Some of the clinic’s NIH funding is devoted to the development of a molecular diagnostic test for syphilis that would allow mothers to be screened faster and more accurately. Existing tests miss nearly 15 percent of congenital syphilis cases—which results in more harm as infections soar. Even experts such as Stafford can have difficulty determining from the test results whether someone has had a syphilis infection in the past or is currently infected. “We’re using tests from the twentieth century,” Sanchez says. “There’s no question we need better diagnostics.”

As Stafford and her team try to help, they’ve recently faced a shortage of injectable penicillin—the only drug approved for use against syphilis during pregnancy and in newborns—largely because of the skyrocketing number of syphilis cases. The relatively few doses that are available can cost more than $1,000 each, a 40 percent increase in the past three years.

So far Stafford has been fortunate to secure medication to treat all of her pregnant patients, but she frets that the shortage will persist and her luck won’t hold. Regardless, she remains determined to continue her crusade against congenital syphilis. “This is my fight,” she says. “It’s one hundred percent preventable. People just need good care.”

Carrie Arnold is a freelance public health journalist from Virginia.

This article originally appeared in the May 2024 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Fighting the Syphilis Surge” Subscribe today.