On a Friday morning last summer, in a windowless courtroom in downtown Houston, Judge Franklin Bynum was performing the daily routine of all American criminal court judges: accepting plea bargains. “I understand you want to plead guilty to trespassing?” Bynum asked one disheveled, apparently homeless man standing in front of the bench. “Yes, your honor,” the man responded. Bynum, a 39-year-old misdemeanor judge with shoulder-length hair and wire-rimmed glasses, peered at his computer, reading the charging document.

“Do you understand that if you plead not guilty, you will be immediately released on a personal bond?” Bynum inquired. “You won’t have to pay anything as long as you keep showing up to court. You don’t have to stay in jail until your trial.” The man seemed nonplussed. “No sir, I did not know that,” he responded. After conferring with his court-appointed attorney, the man decided to change his plea. “Not guilty, your honor,” he said.

This same scene has played out hundreds of times in Bynum’s courtroom since he was elected judge in 2018. Rather than simply rubber-stamping plea deals, as most judges do most of the time, Bynum reminds defendants that they have a Constitutional right to a trial. He also reminds them that, thanks to Harris County’s landmark 2019 misdemeanor bail reform settlement, they can nearly always receive a personal, no-cash bond that allows them to remain free before trial and that only if they violate their terms of release or fail to appear in court will their bond be revoked. Before the settlement, misdemeanor defendants who couldn’t afford their bond had to wait in jail for weeks or months before their trial. Research suggests that such defendants often plead guilty to minor crimes in exchange for immediate release—even when they are actually innocent.

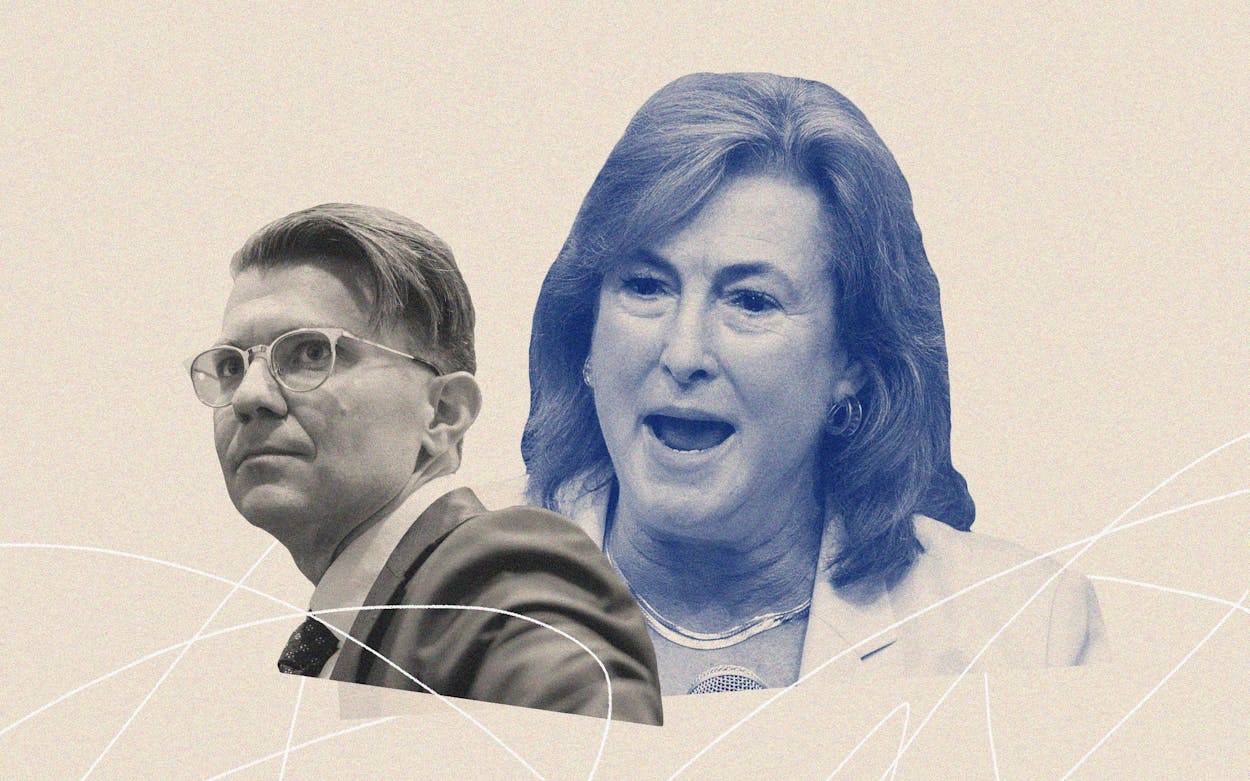

Bynum’s habit of talking defendants out of guilty pleas has infuriated Harris County district attorney Kim Ogg. In 2020, more than a year before the scene I witnessed in Bynum’s courtroom, Ogg’s team filed a 21-page complaint against the judge with the State Commission on Judicial Conduct. “The State understands that no judge has to accept any plea bargain, but such decisions have to be made on a case-by-case evaluation of the agreement, not systematically and arbitrarily,” reads the complaint, which has been amended four times, most recently in October. Bynum “repeatedly and willfully ignored basic principles of criminal jurisprudence and conducted proceedings in his court with an unprofessional and irredeemable bias against the State of Texas and its prosecutors.” What’s more, the complaint states, Bynum releases too many defendants, reduces too many sentences, and has his decisions overruled too often by appellate courts. (Bynum rejects each of these charges in a detailed, 39-page response.)

In addition to Bynum’s reluctance to accept plea bargains, Ogg’s complaint charges the judge with political bias, noting that he self-identifies as a democratic socialist and “prison abolitionist,” and highlighting his very public criticism of the criminal justice system and a photograph of him wearing a “Defund the Police” T-shirt. The SCJC evidently agreed with Ogg. At Bynum’s April hearing before the SCJC, Commissioner Janis Holt, who twice has served as a delegate to the Republican National Convention, took issue with the T-shirt. Noting that her son is a police officer, she told Bynum that “when I see someone who wears a Defund the Police [shirt], it tells me that you don’t care about my son and his family and my granddaughter.” (A SCJC spokesperson declined to make Holt available for an interview, or to answer any questions about Bynum’s case.)

Earlier this month, the panel of thirteen appointees—including six judges appointed by the Texas Supreme Court, five non-attorney “citizen members” appointed by the governor, and two attorneys appointed by the State Bar of Texas—formally recommended that Bynum be suspended from his duties, the harshest sanction it can levy. According to the SCJC, the T-shirt and his media interviews violated the Texas Code of Judicial Conduct’s mandate that “a judge shall conduct all of the judge’s extra-judicial activities so that they do not cast reasonable doubt on the judge’s capacity to act impartially as a judge.” A tribunal of justices from the Texas Courts of Appeals will now review Bynum’s case. They can impose a public censure or removal from office, and Bynum can appeal their decision to the Texas Supreme Court.

Legal experts say that attempting to have a judge removed from the bench, as Ogg is seeking to do with Bynum, is extremely rare. “Actual removal from the bench is reserved for the most egregious behavior,” said Meredith Duncan, a professor at the University of Houston Law Center who specializes in legal ethics and criminal law. “Judges are afforded quite a bit of latitude in the performance of their duties.”

Ogg declined an interview request for this story and did not make a spokesperson available. A staff member provided Texas Monthly with the following statement: “Judges swear an oath to uphold the law and strive for impartiality; the Texas Code of Judicial Conduct mandates that they act in a professional manner and the criminal justice system only works if they uphold their oath.”

Bynum isn’t the only judge who’s been in Ogg’s crosshairs. In 2019, Ogg filed a complaint against Democratic misdemeanor judge Lee Harper Wilson for rejecting the guilty plea of a woman accused of driving while intoxicated because Wilson found her defense attorney “ineffective.” The same year, her office accused Democratic misdemeanor judge Darrell Jordan of treating prosecutors disrespectfully in his courtroom and—like Bynum—displaying a bias toward defendants. Wilson received a public reprimand and was ordered to take three hours of education “in the area of judicial pleas.” Jordan was ordered to take two hours of education “in the areas of judicial temperament and demeanor.” Both remain on the bench.

Ogg has made no secret of her disdain for some members of the Harris County judiciary. For years, she has complained that both felony and misdemeanor judges allow too many defendants to go free before trial. She has alleged that this is a driving factor in the county’s violent crime spike, despite limited evidence that pretrial release decisions are a factor in rising crime—a nationwide trend that is also occurring in cities that have not implemented bail reform. In 2019, her top lieutenant, first assistant district attorney David Mitcham, warned judges that there would be a “reckoning” if they didn’t start setting higher bonds—a warning that at least one participant interpreted as a threat. In this year’s primaries, fourteen of Ogg’s prosecutors, including eight Democrats, filed to run against sitting judges. Six of the prosecutors won—including assistant district attorney Erika Ramirez, who defeated Bynum by nineteen points in the March Democratic primary. Bynum’s term is set to expire in December. But that hasn’t stopped Ogg from trying to get him thrown off the bench in his lame-duck period.

Ogg and Bynum both say they support criminal justice reform, but that’s where the similarities end. Ogg is a former Republican who made her name as the tough-on-crime leader of Crime Stoppers of Houston. She ran for district attorney in 2016 as a Democrat on a criminal justice reform platform. At the time, the county was fighting a major civil lawsuit over its misdemeanor bail system, which plaintiffs claimed violated the Fourteenth Amendment by jailing citizens simply for being poor. (A federal judge later agreed, ordering the county to reform its system.) On the campaign trail, Ogg said she supported reform. Once in office she backtracked, announcing her opposition to a legal settlement that effectively eliminated cash bail for most misdemeanors.

Bynum and Jordan were among the architects of that settlement. They believe Ogg has targeted them, in part, for their role in eliminating cash bail for misdemeanors. “This is one thousand percent political retaliation,” Bynum told me. “I represent all the things in the world that she feels threatened by. She sees the political forces mobilizing for fundamental changes to the [criminal justice] system, and she cannot comprehend them. She has to destroy them. And I am a convenient symbol for those, in her mind.” Jordan told me that “anytime you go somewhere and you make change, then people are going to be upset.”

Some in the Harris County legal community agree that Ogg is seeking political retribution, including Murray Newman, a defense attorney and the president-elect of the Harris County Criminal Lawyers Association, the local defense bar. Newman briefly let Bynum stay at his house in 2012, but is no longer close with him. He supported Ogg when she ran for office in 2016, but has since become one of her most vocal critics. “She’s basically trying to scare the judges into doing what she perceives as best, by any means necessary,” he said. “Look at what she’s done to Bynum. Look at what she’s done to Jordan.”

Elected as a Democrat, Ogg has found herself increasingly isolated within her own party. She is prosecuting three current and former aides of Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo, a fellow Democrat, for allegedly steering a county contract to a politically connected vendor, and is investigating Democratic mayor Sylvester Turner for allegedly steering a city contract to a politically connected developer.

Hidalgo claims that Ogg is pursuing a political vendetta in retaliation for Hidalgo’s refusal to give the district attorney as much funding as she has requested. During her 2020 reelection campaign, Ogg lost the endorsements of progressive groups such as the LGBTQ+ Political Caucus and the Texas Organizing Project.

But it’s not just the left that’s mad at Ogg. She’s drawn recent criticism for losing or being forced to dismiss several high-profile cases, which has raised questions about her competence as a prosecutor. A recent Houston Chronicle investigation showed that nearly half of all felony cases last year in Harris County—and 73 percent of misdemeanor cases—end with prosecutors dismissing the charge, for an overall dismissal rate of 58 percent. (By comparison, that percentage is similar to Austin’s Travis County, but far higher than in San Antonio’s Bexar County, where 46 percent were dismissed, or Dallas County, where 33 percent were.) Ogg has blamed the high dismissal rate on judges having too-high standards for what constitutes probable cause—a charge she also made against Bynum in her complaint to the SCJC. But in a private December 2019 meeting between Ogg and all the misdemeanor judges, one judge after another said they had little choice but to deny probable cause, given the sloppy work of prosecutors.

“A lot of times on probable cause cases, it’s because it was the wrong charge,” said Judge Andrew Wright in a recording provided to Texas Monthly by Bynum, who attended the meeting. “They might be charging someone with interference with public duty, when it clearly isn’t. It might be resisting arrest. I can’t go to the media and say anything, but you guys can send memos and letters and all sorts of things that are super-slanted against the judiciary, making us look like we’re just up here doing whatever we want.” Another judge faulted the lack of trial lawyers in the intake division, a 24-hour-a-day unit of prosecutors that determines what charges to file against criminal suspects. “I think it’s just valuable having people that are trying cases, and know how to evaluate cases from that perspective,” Judge David Singer said.

Ogg responded by defending her intake division. “We believe the people that we hire for intake, based on their experience—either with us or other agencies—are capable of doing the job.”

Some judges and defense attorneys also blame the high dismissal rate on Ogg’s trial prosecutors, who they say are inexperienced, overworked because of the unusually high staff turnover, and lacking leadership. Immediately after taking office in 2017, Ogg fired dozens of veteran prosecutors in an effort to “change the culture.” By 2019, more than 140 prosecutors had left the office. In subsequent years, many more prosecutors have resigned or been fired, for reasons including sharing an innocuous internal document with colleagues.

“The first thing she does is fire all of her experienced prosecutors,” said Newman, the defense attorney. “All of a sudden she starts losing cases, and Kim is somebody who definitely doesn’t want to take the blame. So she’s got to find somebody to blame, and the judges are pretty much the only ones. She can’t say, ‘Oh, it’s just that the defense attorneys are too good and they’re kicking my ass.’ She certainly can’t admit her prosecutors don’t have the experience or training they deserve. So the judges are the last ones standing.”

Since the 2019 meeting, Ogg has stepped up her attacks on the judiciary. She has called the bail reform settlement—which was negotiated by the misdemeanor judges under a court order—“a driving factor in the crime crisis gripping our community.” In September, she released a report connecting the settlement to the crime spike. Four reports from the independent, judicially appointed monitor for the bail reform settlement have found no relationship. The Houston Chronicle’s editorial board characterized Ogg’s findings as misleading: “By singling out bail reform as a root cause of violent crime,” it wrote, “Ogg is tailoring a conclusion to fit her thesis.”

Former first assistant DA Tom Berg, whom Ogg hired as her second-in-command in 2017 and then forced out two years later over a series of disagreements, told me that Ogg is unusually vindictive toward those she considers her enemies. He said that in his four decades of practicing law in Harris County, he had never heard of a prosecutor filing a complaint against a misdemeanor court judge. In 2019, he said, under pressure from Ogg, he signed the SCJC complaint against Jordan. The next year, after leaving the office, he submitted a remarkable affidavit to the SCJC saying he disagreed with the very complaint he had signed. “The judicial complaint was using a nuclear weapon to resolve a petty dispute,” Berg wrote to the commission. “I essentially signed the complaint under protest.”

Newman said the judge bears some responsibility for his predicament. “Don’t get me wrong, [Bynum’s] a weird dude. I get it. And I mean, I’ve been in front of him when he gives [prosecutors] fits. But the stories of defense attorneys going in front of judges they didn’t feel were fair to them could fill a library—and then you get one who makes the prosecutors feel like that.”

For decades, Harris County prosecutors were the kings of the criminal justice system, making Houston the death penalty capital of the world and, civil rights advocates allege, running roughshod over defendants’ rights. Thanks to political and legal pushback, prosecutors no longer have such free rein. Even if Ogg succeeds in kicking Bynum off the bench, her prosecutors will still face fifteen other Democratic misdemeanor judges who continue to back the county’s bail settlement. In many ways, Ogg’s battle is just beginning.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Houston