Imagine a sign by the egg case at your local H-E-B: “Take a dozen home. Please. We’ll pay you $4 per carton. No limit per customer.”

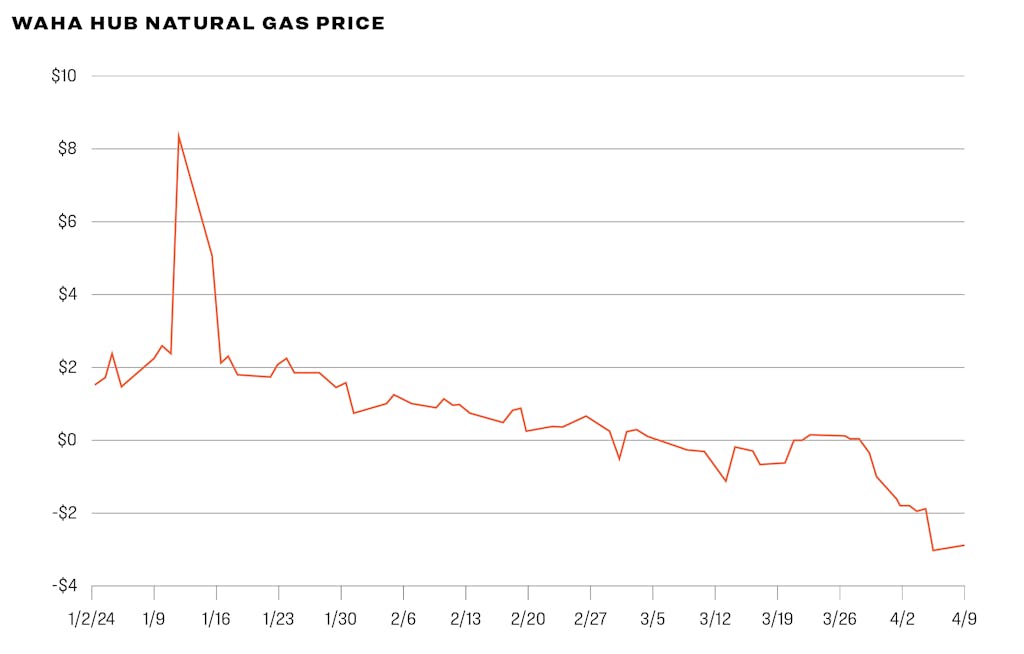

Sound outlandish? Maybe, but this is essentially what has happened with natural gas in West Texas in recent days. Last weekend, the price for gas at the Waha Hub, a major pipeline junction near Fort Stockton, was -$3 per thousand cubic feet. That’s negative three dollars. If you sent gas to Waha, you had to pay someone to take it off your hands.

You may now be saying to yourself, “I’d like some of that gas. I use natural gas to cook dinner every night. Can I get paid to burn gas?” The answer to your question is: Not unless you own a pipeline between West Texas and your house.

By the time gas gets to a pipeline hub that feeds cities and towns and a gas utility purchases it to resell to homes, prices are well above zero.

Who, then, is benefiting from this negativity? It’s hard to say, because the markets are opaque, but the likely answer is energy traders who have long-term deals granting them space in pipelines out of West Texas. When prices fall below zero, these traders get paid to take gas from the Permian, then get paid again when they resell it on the other end of the pipeline: say, in Houston or Quartzsite, Arizona, where the pipeline system connects to the one that feeds Southern California.

Gas is not some nuisance energy by-product. It is an efficient, versatile source of fuel. It generates nearly half of Texas’s electricity and is used to make fertilizer and plastics found in everything from hearing aids to automobile bumpers. In parts of the world, gas fetches a premium: wholesale prices recently have been $10 per thousand cubic feet in Asia and $8 in Europe.

But in the Permian Basin, gas is so abundant that for the last month, it has been all but worthless. “It is very painful,” said Steve Pruett, the CEO of Elevation Resources, a private, Midland-based oil-and-gas production company. “For the first time in my career, the Permian has the worst price realization in the country, and it is projected to continue through the summer.”

What is going on? For one, there’s been more gas coming out of West Texas oil wells. With oil prices up more than 30 percent over the past three years, Permian oil output is up 31 percent over that period, while gas production is up 42 percent, even as prices have fallen. Jim Wright, a member of the Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates the oil-and-gas industry in the state, explained to me that there aren’t enough pipelines to carry that much gas elsewhere. He suggested a change to my egg analogy. “It is like an egg producer not having enough trucks to deliver the eggs to H-E-B, and therefore if you have a way to come get the eggs yourself, they’ll give them to you for free—or pay you to take them,” he wrote in an email.

Meanwhile, the price of oil—which has lots of ways to get to market—remains relatively strong, so energy companies keep beginning to operate new wells, which produce even more gas. The profits to be made on oil are large enough that producers can afford to pay to be rid of it. Kaes Van’t Hof, chief financial officer of Midland-based Diamondback Energy, presciently observed in February that “we could run the gas price to zero in the Permian and still make great returns on oil wells.”

Every available pipeline is full right now. “We are stressing the system in order to flow the oil,” said Jay Stevens, research head at Aegis Hedging, a Woodlands-based commodity adviser to energy producers. Adding to the glut, during the past month, a couple of key pipelines have reduced capacity because of needed maintenance—one that heads west toward California and another that beelines to Corpus Christi. As other pipelines filled up, prices plummeted into negative territory.

Help is on the way for gas producers. The giant Matterhorn Express Pipeline, which will take gas from West Texas to Katy, west of Houston, to connect with other pipelines, is 80 percent complete and scheduled to begin operations in the summer or fall, and other pipelines are under construction.

So what are the lessons here? One is that the energy industry sometimes fails at coordination. One might expect the pipelines to be planned, financed, and built on time, but that’s not always the case. The other overarching lesson is that the U.S. has a lot of natural gas.

Exporters have plans to send much of it overseas to Europe, South America, and Asia. But right now, those plans are on hold because the White House has paused new export permits of liquefied natural gas to countries that

the U.S. does not have a free trade agreement with, in order to study the impact of exports on domestic gas prices and the climate.

This has earned rare bipartisan condemnation from the Texas congressional delegation. In opposing the pause, August Pfluger, the Republican congressman who represents Midland, argued that “energy security is national security.” Separately, Marc Veasey, a Democratic congressman who represents parts of Dallas and Fort Worth, has also called for more LNG exports. “The export of U.S. LNG fosters strong alliances and partnerships with our global counterparts,” he wrote in February in a letter signed by five other Democrats in the Texas delegation.

These statements were issued when Waha prices were $1.55 per thousand cubic feet of gas. They closed last week at negative $3.04.

Disclosure: Texas Monthly’s chair is also chair of the managing partner of Enterprise Products Partners LP, a midstream energy company with interests that include pipelines and storage facilities.