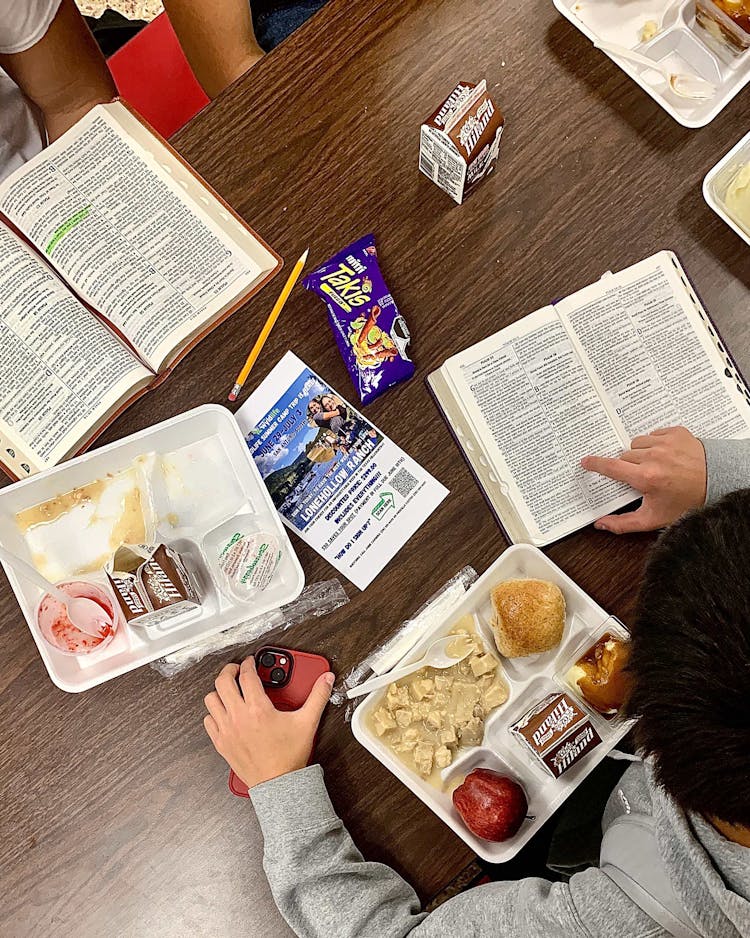

The lunch hour at Harlandale Middle School, on San Antonio’s South Side, is one of the only times during the school day students are allowed to use their phones. Between the streams of incoming notifications and the rumble of preteen socializing, the short period slips by quickly, and loudly—which makes the Bible-study session at the back corner table all the more notable.

Since the beginning of the winter semester, ten 13- and 14-year-old boys have met weekly with Jaime Carmona, a 23-year-old part-time campus minister who seems to vibrate with excitement when he talks about Jesus. The teens bring their Bibles, move through the lunch line to retrieve their food on styrene trays, and huddle around Carmona as he emphasizes core Christian beliefs regarding sin, Jesus’s death and resurrection, and God’s unconditional love. The simplicity of his message is typical of that promulgated by WyldLife, the middle school branch of national teen outreach ministry Young Life. No one is overly serious in any Young Life setting. Participants embrace silliness in a way that somehow makes them seem even more earnest. At Harlandale’s Bible study session, at least one boy is always moving around or cracking a joke.

On the day I observed him, Carmona was teaching a story from the Gospel of John in which some local leaders caught a woman committing adultery and brought her before Jesus to be condemned. In the story, Jesus utters the famous words from John 8:7—“Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.” Carmona drove home the lesson: “The only person who will never judge you is the one who knows you best.” One of the boys nodded, then gave it a different spin: “You gotta trust God. God won’t cheat on you like those hos do.”

When Republican state senator Mayes Middleton laid out the goals of Senate Bill 763, which became law in September and allowed school districts to employ chaplains instead of licensed school counselors, one of his lines made the rounds among national media and First Amendment watchdog groups: “Our founding fathers never intended separation of God from government,” Middleton said. “And what this bill does is make sure our schools are not God-free zones.” While the bill, and its rationale, set a national countermovement in motion, it also perked up the ears of the leaders, mentors, and ministers who work with religious groups such as Young Life. What Middleton and his ilk seem to miss is that nothing encouraged by the new law is as sincerely evangelistic as what is already happening on many middle school and high school campuses all over Texas.

“There’s a misconception that schools bar the door to anyone who wears a cross or carries a Bible,” said Brian Woods, deputy executive director for advocacy at the Texas Association of School Administrators. When he was superintendent of San Antonio’s Northside Independent School District, with its more than 100,000 students, every high school and middle school in the district hosted some sort of Christian campus outreach group.

Young Life reports that it has had some level of interaction—ranging from brief onetime introductions to regular Bible studies—with 82,865 students on at least 409 Texas middle school and high school campuses. It is only one of several ministries bringing Jesus to public school campuses every day. Others include the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and Youth for Christ. In contrast to the school-chaplain law, which dumped state-level politics onto 1,200 school boards, campus outreach ministries’ access to students is determined at the most local level possible: the individual schools. In most cases, the principal of the school gets to decide whether an evangelist for Jesus gets a visitor badge, a faculty ID, or kicked to the sidewalk.

WyldLife was already active at Harlandale Middle School when Andrew Martinez, whose smile and positive demeanor make him look even younger than his 39 years, became the principal in 2021. As he assessed the various programs on campus, he let the group continue its work. “These are positive relationships that have a positive effect on campus,” Martinez told me. Carmona and his equally effervescent boss, Young Life area director Priscilla Castro, both graduated from Harlandale ISD, so they can relate to the kids. Plus, Carmona and Castro don’t have the same authority that teachers and the administration have, so kids are more willing to talk to them. But ultimately, the call to keep WyldLife was an easy one, Martinez said, given the religious homogeneity of Harlandale ISD students, who are mostly Hispanic and Catholic or Protestant Christian. He hasn’t yet met anyone who would be offended by a Christian club on campus.

Across town, things are very different, said Jake Aschbacher, a Young Life area director who oversees two high schools in North East ISD, a larger, partly suburban district. At Reagan High School in San Antonio’s relatively affluent Stone Oak neighborhood, Young Life is not allowed on campus at all. Aschbacher, whose presence radiates something between sketch comedy and a warm hug, met with the principal to explain his willingness to abide by guidelines that suburban schools in neighboring districts have imposed. In some schools, for example, the Young Life representatives must be invited by a student to enter the lunchroom but cannot conduct a Bible-study session, while at others, they may set up an information table but not approach students at all. Administrators know their communities, and they want to make it abundantly clear that they are not allowing proselytizing adults on campus.

Young Life obeys whatever restrictions a community is comfortable with, said San Antonio regional director Annie Mays. As a parent of three girls of elementary school age, she appreciates “no approach” policies, because she said she wouldn’t necessarily want ministers from other religions trying to convert her children. She also recognizes the need for teachers and staff to know who’s on campus. As a young, zealous Young Life staffer in Harlandale at the beginning of her ministry career, she might have pushed the boundaries, she said, but now she tells her staff to play by the rules.

Religion is enmeshed in American history and civic life—two subjects that many parents, teachers, and politicians agree do belong in public schools. Debates arise over which religions are taught and how they’re presented. This kind of negotiation has been going on for almost as long as there have been public schools, said Rutgers University education historian Benjamin Justice, coauthor of the book Have a Little Faith: Religion, Democracy, and the American Public School. Because schools teach civics, history, literature, and life skills, they are steeped in community values, leaving schools to balance the needs of religious majorities and minorities. Most often, he said, they find the lowest common denominator. If the community, like Harlandale, is both Protestant and Catholic Christian, it can agree on Jesus. If the community is largely Jewish and Christian, it can probably agree on the Ten Commandments. The more diverse a school becomes, the more religion disappears from the content. “It has to be that way,” Justice said, because public school principals, teachers, and other staff are well aware of their obligation to protect the rights of minorities.

That’s the law. Many schools open sporting events and awards ceremonies with a prayer, but if anyone complains about it being compulsory, that person has legal precedent on their side. Such a situation can make some members of the religious majority anxious.

Many crusaders for more religious observance in public schools cite the 1962 U.S. Supreme Court decision Engel v. Vitale as the moment when God was driven from our schools. In that case, the high court ruled that prayers composed and mandated by school officials violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which forbids Congress from passing any law “respecting an establishment of religion.” Ever since, politicians have been arguing over what that decision requires. In 2012, for example, cheerleaders in Kountze ISD, about forty minutes northwest of Beaumont, started emblazoning Bible verses on the run-through banners for the high school football team. Some of the cheerleaders told Spectrum News that messages such as “I can do all things through Christ which strengthens me. Phil. 4:13” and “But thanks be to God which gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ. 1 Cor. 15:57” were more uplifting than slogans along the lines of “Let’s kill the other team.”

The Freedom From Religion Foundation, a Wisconsin-based nonprofit promoting the separation of church and state, sent a complaint to the district, which told the cheerleaders to stop creating the banners; the cheerleaders sued the district to allow them to continue. It was a good example of the establishment clause’s limits. The cheerleaders were expressing their religious beliefs. But they were also representing the school in an official capacity at events at which football players, band members, and others were required to be present. Attorney General Ken Paxton intervened in the case, filing an amicus brief with the Texas Supreme Court, which ultimately declined to hear the school district’s appeal regarding its authority to control what the students put on the banners. The court also did not weigh in on whether the use of the Bible verses violated the establishment clause. “Religious liberty is the foundation upon which our society has been built,” Paxton said at the time. “The Texas Supreme Court’s decision ensures that the Kountze cheerleaders and other cheerleaders across the state will be able to display their expressions of faith on banners at football games.” That ruling represented a highly specific win for keeping Jesus in school.

Twelve years after FFRF’s complaint, the fights continue. In the 2023 legislative session, lawmakers considered three bills aimed at making Christianity more visible in public schools: the school-chaplain bill, which passed; a bill requiring the Ten Commandments to be placed in every public school, which did not; and another that would enable school districts to create a period in public schools for prayer and Bible reading. While that last measure did not pass, some Texas public schools have already instituted an elective period dedicated to the Bible.

When James Rhea was hired a year ago to teach U.S. history and coach football and track in Grand Saline ISD, near Tyler, it happened that the district was trying to fill another role: the Bible-study teacher. The previous teacher was retiring, and the district needed someone with subject matter qualification to teach a class that aligned with the Texas Education Code’s section 28.011, which outlines optional electives covering the Old and New Testaments. It just so happened that Rhea was that subject matter expert, so, as often happens in small school districts, the coach agreed to wear yet another hat.

Since 2009, districts have been allowed to offer Bible survey electives, as long as the courses follow “applicable law and all federal and state guidelines in maintaining religious neutrality and accommodating the diverse religious views, traditions, and perspectives of students in their school district,” according to Texas Education Code. The course cannot promote Christianity or hostility toward other religions. That’s not difficult for Rhea. He’s been a Baptist preacher for 50 years and has taught high school history for 47 of them. He’s been managing the separation of church and state his whole career. “We don’t teach religion, but we do teach that you have freedom of religion,” he told me.

Rhea decided to use an introductory college-level classic, The Bible Book by Book, by Josiah Blake Tidwell, as the class text. It provides a basic outline of the Protestant Bible, along with its historical context and authorship. The summaries align with Tidwell’s fundamentalist reading of the Bible in 1914, four years after he founded Baylor University’s undergraduate religion department. It’s not the textual criticism one might find in a religion course at a state university, but neither is it evangelistic. When the local CBS affiliate asked whether Grand Saline ISD would consider a class on the Quran or the Torah, superintendent Micah Lewis said it would if there was enough interest. In Rhea’s class, there’s no spiritual guidance—what Christians call discipleship—other than what students might glean from their readings of the Bible. Rhea leaves discipleship up to the school’s Fellowship of Christian Athletes chapter, another campus outreach group.

Since FCA campus outreach staff are not employed by the district, they can speak more directly about faith than Rhea can. They can also express beliefs that many might find offensive. Both FCA and Young Life have come under fire for their views on sexuality. Neither organization allows its leaders—student or staff—to have a romantic relationship with someone of the same sex. Many students don’t know this policy, and both organizations attract LGBTQ teens who attend events and Bible studies. Some get deeply involved, only to be shocked later when they find out the organization believes their sexuality is sinful.

To avoid sectarian debates—and running afoul of the churches that support them—campus ministries often say that they teach “just Jesus” or that they read the Bible without an interpretive bias. (While it’s a sincere approach, it’s incorrect. Christian denominations have historically disagreed on everything from homosexuality to whether Jesus’s death was a blood sacrifice for human sin—and the teachings emphasized in every ministry are based on interpretation.) Young Life and other campus ministries all grew out of the evangelical Christian movement that emphasizes a personal relationship with Jesus and a dedicated lifestyle, what they would call a Christian “walk.” They talk a lot about sin, but Young Life also emphasizes grace and forgiveness. Messages of nonjudgment, such as the ones Carmona expressed during his lunchtime Bible-study session, are common. While teachings can still get moralistic—plenty of folks have told me that their high school campus ministry talked a lot about saving sex for marriage, not drinking, and wearing modest clothing—there’s a component of this highly relational, character-based mentorship that does seem to help students weather the challenges of adolescence. For every student or former student who is bothered by the ministry’s stance on sexual purity (read: heterosexual monogamy within the covenant of marriage), there are others ready to tell the story of how Young Life stood by them through a tough time.

For John David Benefield, the message of nonjudgment saved his high school experience. The son of a small-town pastor in Mason, in the Texas Hill Country, Benefield got into trouble (he did not want to be specific) during his junior year and became grist for the local rumor mill. One mistake is all it takes in a small town. His Young Life friends were the only ones who kept hanging out with him, he told me.

Upon graduation, he studied agricultural economics at Texas A&M, earned his bachelor of science degree, and came back to Mason to work as an electrician. He now volunteers with the Young Life ministry there. He knows a lot of kids growing up in Christian culture who feel that they’ll be loved only if they obey the rules. He wants them to have what he had: acceptance that will accommodate their evolving, impulsive teenage behavior. “That’s what Christ’s love looks like,” he said.

Upon the school-chaplain bill’s passage by the Texas Legislature, local and national challengers demanded to know whether those of Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim, Odinist, Satanist, Wiccan, Zoroastrian, or other faiths would be hired as chaplains—whether the state would support those religions equally. No one in authority really answered the question.

Attached to the new law was a requirement that every school district vote on whether it would allow schools to hire chaplains. Rather than holding a straight up-or-down vote, most school districts shimmied through a third door: they reiterated existing policies that allow ministers and chaplains on campus in a volunteer capacity. The policies don’t exclude non-Christian faiths.

It’s possible, Brian Woods from TASA allowed, that some rural districts might feel hiring a chaplain is their best shot at finding someone for a hard-to-fill counselor position. But many chaplains observe that what they do and what counselors do are very different. In August, after the chaplain bill passed, more than one hundred chaplains signed a letter urging school boards to vote against hiring them, saying, “Professions which help children with sensitive matters, such as therapists and police investigators, typically require special training on how to interview and treat juveniles. Few chaplains have this expertise.”

Mays said that Young Life staff have to report to schools—or, in some cases, to Child Protective Services—if they become aware that a student is suffering from abuse or serious mental health issues or might pose a risk to themself or others. Staff members frequently partner with school counselors and social workers when it’s clear a teenager needs professional help. Early last fall, she said, she noticed that one of her students—a football player whose high school experience had been radically altered by the COVID-19 pandemic—stopped coming to club meetings. When he showed up at school at all, he was in pajamas, often with a blanket over his head. She tracked him down only to have him tell her that making an effort in school was pointless, and that he didn’t necessarily plan to graduate. Mays contacted the school’s social worker and had Young Life staff continue to reach out to the student while the social worker created an intervention plan. Now the student is on track to graduate, has saved enough money to buy a car, and plans to participate in a Young Life camp this summer as a volunteer.

“It’s important for us to know who we are and who we aren’t in Young Life. Most of us aren’t licensed mental health professionals, and we definitely don’t replace them when medical care, professional help, and a formal plan is needed,” Mays said. “We’re a friend to call, a cheering voice in the stands, a phone number they can text after hours.”

In Harlandale, Martinez also doesn’t see chaplains of any sort as substitutes for the mental health resources he has on campus. His school employs three academic counselors and a social worker and participates in Communities In Schools—a drop-out prevention program focused on academic and social support. That’s the “huge umbrella” of services his kids need, he said. “There’s no substitution for that.”

The only ones who seemed to think that chaplains could substitute for trained counselors were lawmakers. Woods doubts they’re paying much attention to the legislation’s lack of impact. The bill was passed, he said, to please far-right megadonors. “It’s checking a box on the Christian nationalist scorecard. [Lawmakers] don’t care about it one way or another.”

But for those who do believe that religious faith has something to offer to public school students, the tepid reaction to the chaplain bill has been reassuring. For the campus ministers laboring to make inroads with students, their chaplaincy services have been deemed sufficient representation of Jesus on school grounds. For the licensed counselors and social workers who have been educated and trained specifically for the Olympian task of providing mental health services in public schools, their services have been reaffirmed as irreplaceable.

- More About:

- Texas Legislature

- Public Schools

- San Antonio