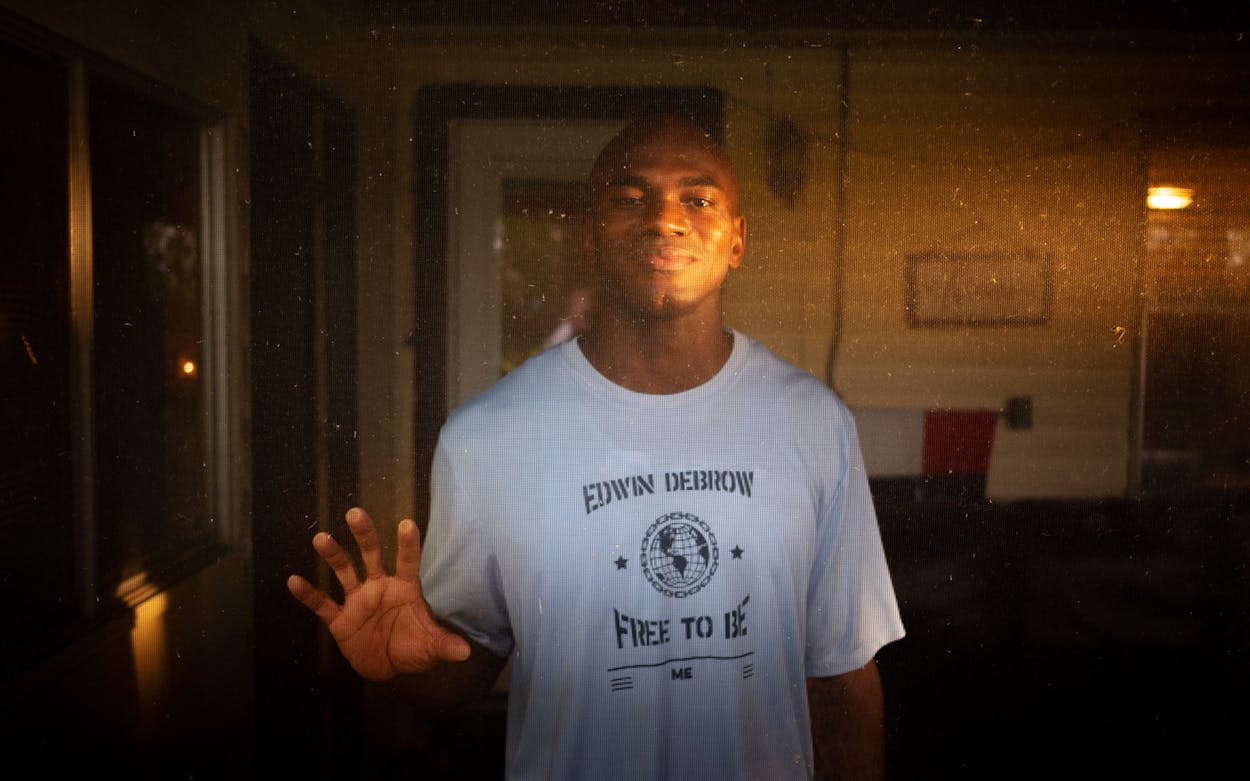

On a Tuesday morning, August 27, guards led forty-year-old Edwin Debrow into a small room at the Carol S. Vance Unit, a state prison just outside of Houston. The convicted killer took off his white inmate’s uniform and put on a new pair of blue jeans, new white socks, a new pair of blue Nike Air Max 270s, and a light blue T-shirt that read:

Edwin Debrow

Free to Be Me

“I’m ready,” he said, a grin slicing across his face. “I’m so ready.”

The last time Debrow had been in “civilian clothes,” as he called them, was September 27, 1991, nearly 28 years ago. He was then twelve years old, only four feet eight inches tall. That day, he was wearing an unwashed T-shirt, basketball shorts that came down to his knees, and unlaced tennis shoes, and he was hanging out in the living room of his mother’s meager San Antonio apartment. There was a knock on the door. Homicide detectives walked in and arrested him for murder, claiming he had shot a taxi driver named Curtis Edwards in the back of the head a few nights earlier during an attempted robbery.

Almost overnight, Edwin became one of Texas’s most notorious criminals. People were stunned that such a small child could have committed such a cold-blooded killing. In a speech addressing the problems of the inner city, President George H. W. Bush went so far as to single out Edwin, describing his behavior as “truly horrifying.”

At his juvenile court trial, his feet barely touched the floor as he sat at the defense table. He received a 27-year sentence for murdering Edwards. For five years, he was incarcerated in various Texas Youth Commission juvenile prisons known as “state schools.” At age seventeen, he was transferred into the state’s adult prison system, which included some of the harshest correctional facilities in the country. “I’m considered the bad seed, the worst of the worst,” Edwin said when I first went to see him in 2011. “All because of one stupid, terrible thing I did when I was twelve years old.”

Debrow grew up in the projects on San Antonio’s east side, where his life was marked by poverty and neglect, drugs and gangs, knifings and gunfire. He was unquestionably a violent boy, known around his neighborhood as the “Baby Gangsta.” At the state schools following his murder conviction, he viciously fought guards and other teenagers. When he was moved to adult prisons, he kept fighting, at least for a few years, even stabbing another inmate with a shank.

By his mid-twenties, however, after a decade behind bars, Debrow started changing. He renounced his prison gang membership, earned his high school equivalency diploma, took junior college classes in computer science and business administration, read self-empowerment books, and wrote an autobiography in which he expressed deep regret for the way he had lived his life.

At one point, Debrow became a jailhouse lawyer of sorts, helping other inmates with their legal appeals. He found flaws in his own court record, which he used to get a new trial in 2007. But in a twist no one saw coming, prosecutors at that trial brought up his previous acts of prison violence and persuaded the jury to add thirteen more years to Debrow’s original sentence, which meant that he would not be released until September 2031, when he would be 52 years old.

After that verdict, Debrow didn’t revert to his old ways. He stayed straight as an arrow. Still, every two years, when he applied for parole, the state board turned him down, always citing the severity of his crime.

I wrote a story about Debrow for the January 2017 issue of Texas Monthly. By then I figured he had no chance at getting out of prison early. But after my article was published, Sheila Bryan, one of Debrow’s elementary school teachers who had stayed in touch with him, and her husband Brett, decided to hire a criminal defense lawyer, Mary Samaan of Houston, who specializes in representing inmates eligible for parole. “I always believe in second chances,” Sheila Bryan told me. “And I always have seen such possibility in Edwin.”

Samaan put together a packet of information for the parole board. She noted the findings of neuroscientists who concluded that the brains of juveniles are not fully formed and that, over time, even juveniles who have committed wretched crimes are able to control their impulses and change for the better. Samaan included letters from several of Debrow’s supporters, from Bryan to Dr. Elizabeth Topitzer, a well-regarded New York City psychologist who had developed a letter-writing friendship with Debrow. She added a report from the warden at the McConnell Unit outside of Corpus Christi, where Debrow was then incarcerated, that laid out Debrow’s record of good behavior.

In October 2017, the board agreed to parole Debrow, but they ordered that he first complete the “InnerChange Freedom Initiative,” an eighteen-month, religious-based pre-release program at the Vance Unit. He was transferred to Vance in January 2018 and assigned to work in the computer lab. He attended church and group counseling sessions and a Christian-based Alpha course. Beth Morrow, a volunteer who taught the Alpha course, told me that Edwin never missed a session. “He was really special,” she said. “He stood out, determined to embrace a better life.”

Another woman who came to know Debrow during his time at Vance was Megan Risdon, a 36-year-old single mother of two young children who lived in Missouri City, a community south of Houston about a twenty-minute drive from the prison. One of her friends happened to mention that she had been corresponding with an inmate who was close to the infamous Edwin Debrow. “My friend said, ‘Edwin is supposed to be really nice. Maybe you should write him a letter,’” Risdon recalled. She went online and read about Debrow. “I thought, what would I possibly have in common with this guy who has had the opposite life of mine?” she said. “Surely, this is not to be.”

Nevertheless, Risdon felt some sympathy for Debrow, and she wrote him a letter of encouragement. He wrote back. She soon registered her phone number with the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, and on September 25, 2018, Debrow called her collect. They talked for thirty minutes, the maximum time an inmate was allowed for a collect call. He called her the next day and then the next. He put her on his visitor’s list, and she went to see him in October. In these initial conversations, he told her about his years in prison, but he also asked questions about her life. “He made me feel extremely comfortable,” she said. “And I could tell he valued me. He made me feel that I was important.”

Debrow continued to call her each day. Sometimes, if a phone was available, he called her three or four times a day. When she went to see him a second time, he threw his arms around her and kissed her. “She made me happy,” Debrow told me. “She was full of love.”

In late 2018, Sheila Bryan, Debrow’s elementary school teacher, came to the prison and tearfully told him she had to back out of her offer to let him live in her San Antonio home whenever he was released. Her husband had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

Debrow was devastated. He didn’t want to return to San Antonio’s east side, which remains rife with the temptations of the violent life he’d long ago left behind. Fortunately, Risdon stepped in and told Debrow he could live with her at a small home she planned to rent in Pearland, another community south of Houston.

Risdon’s parents were wary when they learned what Megan planned to do, but they offered to help her and Debrow start their new life together. Many of her friends, on the other hand, were stunned and told her she was putting herself and her children in danger by falling in love with a murderer. “I said, ‘He was twelve years old when he did what he did. And you really think he shouldn’t be forgiven? Come on. You need to get to know him. Edwin is no killer,’” Risdon told me.

And now, on this August morning, after spending much of his childhood and all of his adult life behind concrete walls topped with razor wire, Debrow was about to walk into the free world. Gathered in the parking lot were members of his family who had driven from San Antonio. (One of his brothers, Dinky, wasn’t there. He had been fatally shot in 2018 during a gang altercation outside a barbecue restaurant.) They too were wearing the blue “Free to Be Me” T-shirts that had been made by another of Debrow’s Houston-area supporters, Charlotte Pendergraft. “In prison, Edwin has had to live the prison way of life, with all its rules and regulations,” Pendergraft said. “He’s never been able to be himself. Just imagine what a moment this will be for him.”

As part of his parole, which will last for twelve years, Debrow is not allowed to contact members of the family of Curtis Edwards, the man he shot to death. “That tears me up,” he said. “I know his mother doesn’t forgive me. I want to write her and let her know how sorry I am and that I will do what I can to live as honorable a life as her son had lived.”

Debrow walked out of the prison gates flanked by Bryan and his mother, Seletha Thomas. The few dozen people waiting for him in the parking lot began to cheer. In the prison dormitories, inmates watched Debrow through screened windows crisscrossed by bars, “Free at last,” one inmate shouted. “Thank God almighty. Free at last.” Debrow turned, raised his hand in the air, and shouted back, “It’s your turn next.”

Risdon drove him to her house. He spent most of the ride fiddling with a cellphone she had bought him, calling and texting people he knew, including a member of the state’s parole board who had taken a special interest in his case. He studied the phone’s screen. “There’s the Uber app,” he said to Risdon. “I watched a story about Uber on television.”

Like many inmates, Debrow had been an avid television viewer in the prison day rooms, watching whatever was on: news shows, commercials, sitcoms, home shopping networks, even the Ellen DeGeneres talk show. It was his only way, he once told me, of keeping up with all the changes taking place on the outside. “I wanted to make sure I wasn’t left behind,” he said.

Nevertheless, he looked a little shell-shocked. At Risdon’s home, people arrived with food he hadn’t eaten in nearly three decades—Church’s fried chicken, Shipley donuts, chips and salsa, fresh fruit, kolaches. Bryan brought chocolate-covered pretzels that Debrow and his classmates used to make in her classroom. Someone else brought soft drinks. “Man,” Debrow said. “I don’t know where to start.”

He sunk down in a couch in the living room, underneath a ceiling fan. “Haven’t been on a couch since the day of my arrest,” he said, smiling. He noticed a placard on a wall that read, “Home is my happy place,” and smiled again. “I didn’t see anything like that in prison,” he said.

Then, after a couple of hours, he made it clear that he was ready for his guests to leave so he could be alone with his girlfriend. “I haven’t been thinking about much else the last couple of days,” he said as Risdon blushed.

I called Debrow a week later. He told me he had been applying for jobs—at a construction company, at Union Pacific Railroad, at a warehouse, at an H-E-B grocery store, at an electric power restoration company—but so far, no one had called him back. Debrow already seemed caught in the trap that catches so many ex-convicts who serve their time but are deemed unemployable because of their criminal records.

I asked him if he was having any other difficulties adjusting to life outside prison. “Well,” he said, “I still wake up at 3:30 in the morning, which is the time I had to wake up when I was incarcerated. And I’m still used to hard beds with thin mattresses, you know, so it’s been an adjustment to get used to Megan’s soft bed. And we were in a Best Buy today. It was crowded, and there were people behind me, and for a minute I wanted to turn around real fast to make sure no one was trying to slip up on me.

“But then I realized that was prison thinking. I realized that I don’t have to worry anymore about always watching my back. I’m now living in a quiet neighborhood. I get to play with Megan’s children. I get to take my shoes off and run in the grass.”

Debrow laughed out loud. “Listen, this afternoon, we bought steaks to eat tonight. I never got to eat steak in all my years in prison. So who am I to complain? I’m a free man…”

He said it again. “I’m a free man.”

This story was updated to include additional information about the terms of Debrow’s parole regarding contact with the victim’s family.

- More About:

- Prisons

- San Antonio