When I read last week that former Enron CEO Jeff Skilling was being released from federal prison to a halfway house in Houston, my first thought was of Rip Van Winkle. After all, Skilling went to the big house way back in 2006, when people were still using BlackBerrys instead of iPhones and Donald Trump was a Democrat and just another Manhattan blowhard. Saddam Hussein was the world’s worst bad guy, and he was executed by his own countrymen. Democrats couldn’t conceive of a worse president than George W. Bush.

Back then, there was no shame in being a multimillionaire because there weren’t that many billionaires, though the number had grown to around 790 from only 470 in 2000. Even so, the best-selling status cars were measly BMWs and Porsches. Everyone was busy selling or borrowing against a house to pay for more house because prices were sky high. The next year, in a book called How to Build a Fortune, Trump would write that he hoped the housing bubble would burst, because then “people like me would go in and buy like crazy.” It seemed like a lot of people were getting very, very rich in ways that the average person didn’t quite understand.

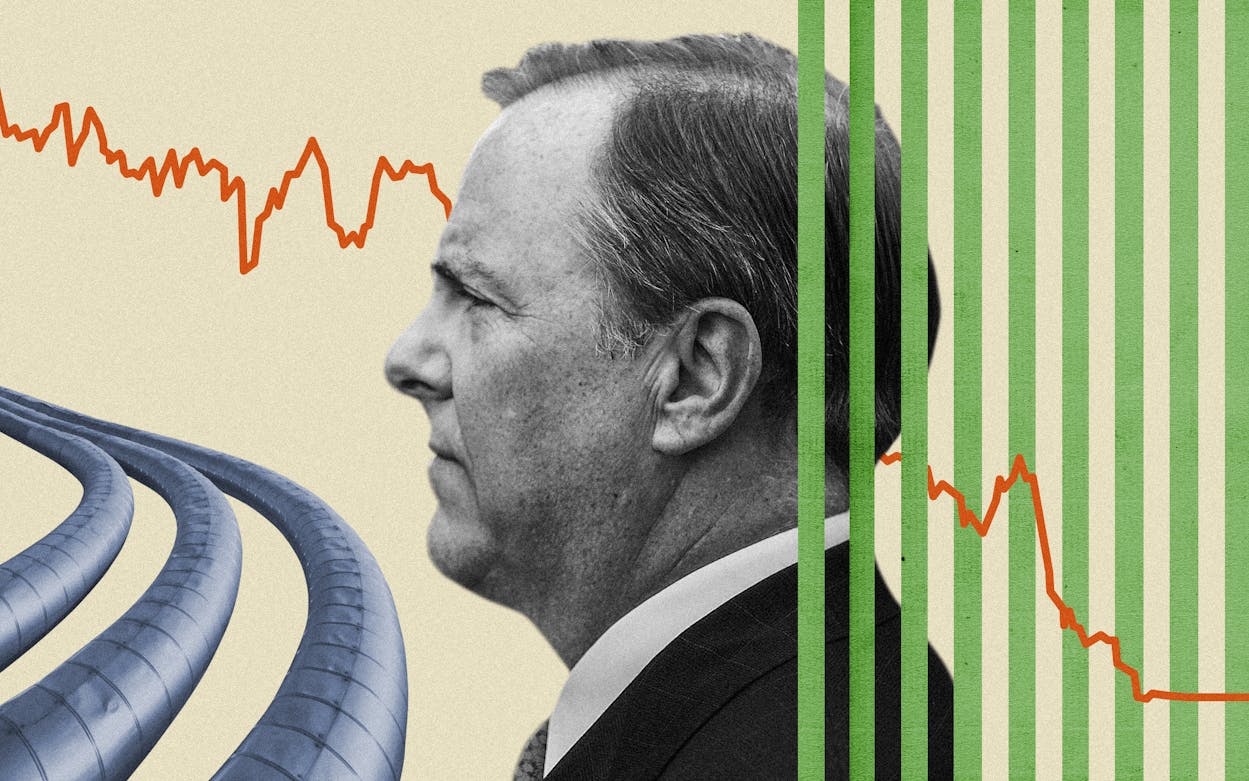

But Jeff Skilling did understand. For those unfamiliar with the Enron saga—at this point the company’s collapse was in 2001, a generation ago—the pipeline, broadband, and trading corporation was for a time the avatar of Houston’s emergence from the oil bust. It was the place where the forward-thinking and brilliant belonged, the company that was supposed to ascend from being the world’s largest pipeline company to the world’s largest company. Enron, valued at $63 billion when $63 billion was a lot of money, was a Wall Street darling, and its leaders were worshiped globally—especially CEO Ken Lay and his successor Jeff Skilling.

Then the whole thing vaporized in the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history, when it was revealed that the part of the company that didn’t have real assets—those boring old pipelines—was not much more than a fantasy built on funny accounting and wishful thinking—or what cynics would call lies. Little people all over the U.S. lost their savings, especially the Enron employees who had put all their money into company stock at the urging of its leaders. But ultimately justice was done: Ken Lay, who had founded the company, was found guilty of ten counts of securities fraud that he probably never understood, and died shortly afterward. Andrew Fastow, the former Enron CFO, spent six years in prison for misleading investors with all-too-clever financial instruments.

And then there was Skilling, the so-called genius behind Enron’s rise. Unlike Lay, whose Midwestern engineering background was pretty humdrum, he was a Harvard MBA who had risen through the ranks at McKinsey & Co., the management consulting firm that, for a time, no successful corporation could do without. (In retrospect, their highest and best use may have been to help corporations fire vast numbers of employees.) At Enron, Skilling preached the newest thing—weather futures! Streaming movies in your home! A new currency! His confidence was messianic, which rewarded him with fall-on-your-sword loyalty from his hard-driving band of executive bros. Skilling was bent on creating the corporation of the future: a company that produced nothing but generated fees for connecting… everything.

There was nothing wrong with his ideas—many have since profited from broadband and Bitcoin—but Enron and Skilling suffered from corporate ADD. Much deal-making and scurrying around was followed by… not very much that was actually concrete. With the collapse, Enron was revealed to be both an unbearable pressure cooker and a seat-of-the-pants operation. Since Skilling had been the architect of the company’s rise, he took the biggest fall: In 2006, a federal jury convicted him of twelve counts of securities fraud, five counts of making false statements to auditors, one count of insider trading, and one count of conspiracy for his role in hiding debt and orchestrating a web of financial fraud that ended in the Houston company’s bankruptcy. For that he got the harshest sentence of any Enron executive: 24 years in prison and a $45 million fine, castigation that shocked even one of the prosecutors. In 2013 the trial judge reduced Skilling’s sentence to fourteen years, which brought his release date to just around the corner, in February 2019. His assignment to an undisclosed halfway house would be his first stop on the road to freedom.

A normal person might assume that the Enron scandal was a teachable moment for everyone in business and finance. Those who do wrong, no matter how high up the corporate ladder, will be punished—that was supposed to be the moral of the Enron story. Skilling’s sentence was intended to be a repudiation of the do-whatever-it-took-to-win Enron Way. Screw your colleague, who was just a whiner or a weakling anyway. Lie to investors, who were dodos if they didn’t take the time to study SEC filings. Demand ever-bigger bonuses because earning more and more and more was the only way to keep score. Who cared whether the whole state of California went dark thanks to market manipulation by Enron traders: you were Enron, and you were entitled. Bully the regulators and the credit rating agencies—they were idiots who didn’t understand money. Buy politicians—they always had a hand out anyway! Rig the system in your favor in every way possible, and humiliate, bully, or just plain stomp (figuratively) on anyone who griped that Enron didn’t play fair.

But the Enron prosecution—especially Jeff Skilling’s—supposedly put an end to all that bad behavior. Justice was served.

For a minute. What’s so striking about the world Skilling will be released into is how much it resembles the Ayn Randian empire he tried to build at Enron. His trial took place just as the housing bubble was bursting, two years before the 2008 financial crisis, the one in which the whole country nearly went under. It turned out there were plenty of folks at the top willing to support the Chump Economy: all you had to do was rope unwitting home buyers into mortgages they could never repay, then convince people to borrow against their mortgages. In the meantime, the same thing was happening on a bigger scale: newfangled investment banks, a product of deregulation—easy credit for all!—turned the loans into financial instruments that could then be transformed into investment opportunities, those so-called mortgage-backed securities. When homebuyers started defaulting on loans they should never have bought in the first place, the stage was set for a disaster that made Enron’s look like a grocery store slip-and-fall case. The Great Recession lasted until 2012. Consumers lost more than $4.2 trillion as of 2014. While Skilling remained in lock-up, the heads of the big banks kept their limos and airplanes and country homes and, of course, their gargantuan wealth. One of the great Enron ironies is that Andy Fastow now speaks to schools and business groups around the country, warning that the kinds of frauds he perpetrated are still part of many U.S. corporations’ playbooks.

That’s the world Jeff Skilling will be returning to: the one in which most of the wealth in this country has been transferred to the kind of person he used to be, one in which the President of the United States continues to oversee the transfer of even more riches to his pals, while ordinary folks try to figure out why they can’t afford to retire and their kids are saddled with massive debt for college educations.

There’s already been one welcome-home party for Skilling by former Enron execs, and there will most likely be more. They know, and he knows, that he was always ahead of his time.