Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts or Spotify. Read the transcript below.

Learn more about the case with original videos, archival photos, and documents from our reporting in our episode guide.

Subscribe

“You want to love your kid forever. But once they pass on, the only thing you can take forward from them is the love that you had for ’em and the good times that you shared.”

—Marshall Stewart

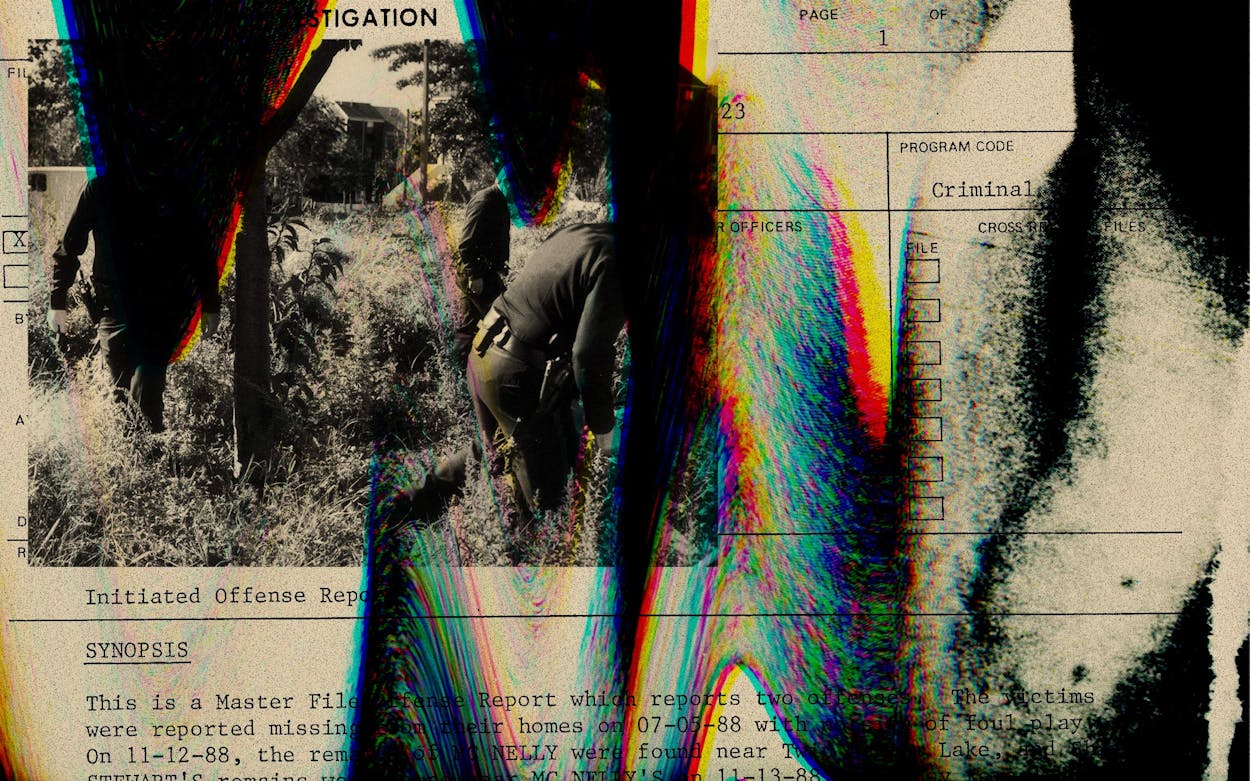

In the final episode of Shane and Sally, victims in a series of unsolved attacks at the lakes surrounding San Angelo wonder if their assailants were also the ones who killed Shane Stewart and Sally McNelly. Investigators discuss the possibility that someone in law enforcement could know more about the murders than they’ve let on. And we explore how new DNA technology and a new cold case investigative unit could finally bring fresh leads in the case.

Shane and Sally is produced and cowritten by Patrick Michels and produced and engineered by Brian Standefer. Additional reporting in this episode by Guill Ramos. Assistant producer is Aisling Ayers. Story editing by Rafe Bartholomew. Executive producer is Megan Creydt. Fact-checking by Doyin Oyeniyi. Studio musician is Jon Sanchez. Artwork is by Emily Kimbro and Victoria Millner. Additional thanks to Mark Hennings for sharing his reporting on the Red Bandana murder case.

Get in Touch

If you’d like to share any thoughts about the podcast, or about the murders of Shane Stewart and Sally McNelly, let us know in the form below.

Transcript

Karen Jacobs (voice-over): If you take a map of Texas and you draw a line north to south, from the top of the Panhandle to the tip of the Rio Grande Valley, and another line from the farthest points east to west, San Angelo would be right about where those two lines cross. It’s near the center of the state. But growing up there, it could sometimes feel like the middle of nowhere.

Three nearby lakes offer a little getaway from town. Each sits on a branch of the Concho River as it flows into the city. There’s Lake Nasworthy, Twin Buttes Reservoir, and O. C. Fisher Reservoir. Each offers something a little different, but they all have something terrible in common: in the eighties, each lake was a site of brutal attacks by masked gunmen. And to this day, these crimes remain unsolved.

On prom night, in May 1988, David Weaver and his girlfriend left their high school dance and drove together to O. C. Fisher. He was seventeen, and she was fifteen. David parked overlooking the water. The stars sparkled on the lake, with San Angelo lit up to one side and the dark expanse of West Texas to the other. It looked like theirs was the only car around. The windows were up; the doors were locked.

David Weaver: And we’d been there about ten minutes, just enjoying the night, watching the stars, and just talking. I’m sitting behind the steering wheel. Laura’s sitting next to me, but had her feet out in the seat toward the passenger door, kind of leaning on me.

That’s when they heard the sound—thump. It was on the driver’s side door. Like someone was trying the handle on the outside.

David Weaver: When I turn and look, I see this guy dressed in old-style Army fatigues, with a black ski mask on. He’s very tall, like six two, six four. He just starts beating the window of the car, trying to smash the window of the car.

After a few blows against the window, the man started beating the top of the car.

David Weaver: Then Laura tries to get out of the passenger door. I grab her; she shuts the door; another guy comes around to the passenger door. I hit the key—I’m cranking the key, and the starter’s just spinning.

David could see the man outside was holding a shotgun.

David Weaver: Puts the barrel on the window and tells me, “Don’t start the f—ing car.” So the starter’s just spinning, spinning, spinning. I let go of the key, and the car started. So I’m looking at this guy’s raging eyes, which [are] all I can see. And out of pure instinct, I drop the car in drive and just floored it.

The car went flying, throwing rocks everywhere. As they sped away, David looked in the mirror and saw a car was chasing them. But once they were out of the park, the car in the mirror was gone.

The experience was horrifying enough, but it took on a new significance two months later, after Shane and Sally disappeared from the very same lake.

David Weaver: I think it’s related, yeah. I think if I’d’ve had my door unlocked, my window rolled down, I wouldn’t be here, just like Shane and Sally. I think I’d have been drug out of the car, and that’d’ve been it. I fully believe that.

Alongside the four suspects you’ve already heard about—along with the occult group, the drug money, the theory about a jealous love triangle—this is yet another theory for what happened. Maybe Shane and Sally hadn’t known their killers. Maybe they’d simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time, attacked by men who’d been preying on victims at the lakes for years.

There were at least four of these violent incidents, from 1983 to 1988. In each case, a couple, or a small group of friends, were parked by one of the lakes when one or two masked men with guns walked up and attacked them. Some managed to get away. Some didn’t. And still, in all of these cases, nobody knows who held the guns, or who wore the masks.

From Texas Monthly, this is Shane and Sally. I’m Karen Jacobs.

Rob D’Amico (voice-over): And I’m Rob D’Amico. This is the final episode: “The Cold Case.”

Karen Jacobs (voice-over): In the early morning hours on a Sunday, in the summer of 1983, Sandy Neatherlin was parked with her boyfriend at Lake Nasworthy.

Sandy Neatherlin: He stepped out of the truck, and three men approached us, and—excuse the language, but they said, “Freeze, motherf—er, or we’ll shoot.” Well, we both kind of laughed about it, ’cause we thought “Okay, you know, it’s just a bunch of friends pulling a prank on us” at first, and we didn’t really think anything about it.

The men were dressed in black, with black hoods. Each wore a ski mask, and they carried guns.

They threw her boyfriend against the truck and handcuffed him. Sandy locked the car, but one of the men broke a window. He cuffed her hands and gagged her.

Sandy Neatherlin: And they said, “Have you ever heard of Charles Manson?” And I shook my head, because I couldn’t talk; I had a gag in my mouth. And they said, “Well, I’m three times worse than that,” and that “this is your worst nightmare.”

The men drove them in the bed of their truck from Lake Nasworthy to Twin Buttes Reservoir—the same lake where authorities later found Shane and Sally’s remains. The men led Sandy’s boyfriend away. And then, she says, the men raped her.

After a time, the men drove off and left her. Sandy found her boyfriend, and they walked to get help. Sandy was taken to a hospital, where a nurse administered a rape kit. She told the authorities what had happened. And then she waited for news.

Sandy Neatherlin: And we never heard anything, never heard anything—and I kept calling and asking them, “Hey, have y’all found out anything?” And after a couple of years, you kind of blow it off, ’cause you keep getting the same answer, “No, there’s no new evidence. There’s no new clues, or nothing.”

Her hope for answers faded, but the memories didn’t.

Sandy Neatherlin: Even though it’s been like forty years ago, during the summer, I won’t even go outside on my front porch, because I am still, to this day, so afraid.

In the first years after the attack, Sandy says she did sometimes hear from authorities—about other attacks at the lakes. They seemed to be wondering if the cases were connected. And today, Sandy wonders if the men who assaulted her could have moved on to murder.

Sandy Neatherlin: After all the years, I’m like, “Okay, Shane and them, they ended up getting killed.” After doing this so many times, was it the same people? Did it get to be to where they just kept getting more and more brave, each time, and then they ended up finally killing?”

In a way, it’s the simplest explanation of all. While investigators were collecting rumors from high schoolers about unholy books and animal sacrifices, should they have been looking for grown men who’d been robbing and assaulting people at the lakes for years?

Pursuing this theory, though, would leave not just one cold case to sift through, but five. And the records in these cases seem just as muddled as Shane and Sally’s.

One report mentions a fingerprint that deputies took from David Weaver’s door. But it’s not clear what came of that. And to this day, Sandy Neatherlin still wonders about the evidence from her rape kit.

Rob raised this question with Terry Lowe.

Terry Lowe: If it exists, it’s not in our evidence locker.

Rob D’Amico: Do you know where it could possibly go, or . . .

Terry Lowe: No.

Rob D’Amico: Would there ever be, like, a chain of . . .

Terry Lowe: Custody?

Rob D’Amico: Paperwork, custody, that would outline something like that?

Terry Lowe: One would think.

Rob D’Amico: I can look into that too, and see what the standard procedure is. I don’t know.

We were sitting in Nick Hanna’s office at the time. And this is when Nick jumped in.

Nick Hanna: Well, I mean, we know what standard procedure is. We’re telling you there’s no standard procedure in 1988 that was followed.

Rob D’Amico: Okay.

Rob D’Amico (voice-over): In the summer of 1986, a deputy named Chris Cherry was assigned to the most brazen of these attacks: a sexual assault and robbery involving five college students. I reached him on the phone last summer. And he volunteered a theory that other officers hadn’t before.

He said my call brought back a flood of memories.

Chris Cherry: Well, I have to tell you that the first time I talked to you, I hadn’t thought about that incident in years. And it brought back sleepless nights for me after you called me.

It was early on a Sunday morning when Chris got the call. Three young women and two young men from Angelo State University had been attacked.

Chris Cherry: I think they were in a band, and they played that night, and they went out to the lake just to chill out, like people do. And two armed men wearing ski masks assaulted them. They handcuffed three of them and, I believe, tied up two of them. With police-style handcuffs.

Then, for three hours, they sexually assaulted the women, and forced the students to sexually assault one another. This is when Chris mentioned that theory—one that we’ve wondered about too.

Chris Cherry: And in the back of everyone’s minds was the possibility that these guys were either involved in law enforcement or had previously been in law enforcement.

There were those “police-style handcuffs.” And then there was something about the attackers’ behavior.

Chris Cherry: They were wearing gloves, and one of them was a smoker. And when he would smoke a cigarette, he would turn his back to them, raise the mask up, take a draw on the cigarette, and then lower the mask back down. He had a Crown Royal bag tied to his belt, and he would put the cigarette butts in the Crown Royal bag, which indicates to me that he had some understanding of police procedures.

It was a striking thought: As the authorities in San Angelo struggled to untangle these violent mysteries, were they chasing one or two of their own?

Chris Cherry: And as you probably know, the psychology of sexual assault is about power and control. And someone who has that kind of personality could be attracted to law enforcement for that very reason. It gives them power over people who are not able to deflect that exercise of power.

As you heard in episode three, former sheriff’s deputy Larry Counts has also harbored suspicions that someone in law enforcement had something to do with Shane and Sally’s deaths. And he even went so far as to name someone: an officer named Randy Swick.

Karen Jacobs (voice-over): Back in 2018, I asked Nick and Terry to tell me about this officer.

Karen Jacobs: So, can you tell me who Randy Swick is?

Nick Hanna: Mm-hmm. Randy Swick is a former . . . He worked for the San Angelo Police Department. And then when he retired, he came to work for the sheriff’s office. He was even a lieutenant with Tom Green County Sheriff’s Office. But his name is in the report a few times. And we know there’s some rumors—we’ve seen the rumors—where he was involved, but I’ve not seen any evidence of it.

Terry told us he’d seen some notes Larry wrote about Randy Swick. But never any evidence against him. In fact, it sounded like the two of them were more skeptical of Larry.

Karen Jacobs: Do you suspect Counts?

Nick Hanna: I don’t suspect him of murder. I suspect that he had more of a relationship with the victims than he’s been up front about.

Terry Lowe: With the victims and Gilbreath.

After all, he’d been meeting with Shane and Sally before they were killed. And Terry said when he asked John Gilbreath how he knew so much about the murders, Gilbreath said he’d heard it from Larry.

So we asked Larry to explain his theory. And here’s the story he gave us. He says this was a few years after Shane and Sally were murdered.

Larry Counts: Now, do y’all know about the psychic that we went and got?

Karen Jacobs: Oh, no. Tell us about that.

Larry Counts: Okay. When we did the Unsolved Mysteries, and we started getting all these—the calls came in—we got several calls that we should talk to this lady in Oklahoma.

Larry heard this woman was a psychic who’d worked with police before.

Larry Counts: Well, Bill McCloud called her, like, three times, and she never answered. So, being the smart aleck that I am, I tell him, “Bill, if she was that good of a psychic, she would know that you’re trying to call her,” and it made him mad.

Larry says they finally connected, and she agreed to help. And Larry says it was actually this psychic who indicated that Randy was somehow involved. No evidence, just that.

Rob D’Amico (voice-over): You’ve already heard from Randy Swick in episode four, talking about finding Sally’s driver’s license on the police department floor. He was one of the first people we reached out to. And I also asked Randy what he thought of Larry’s accusations.

Rob D’Amico: Let’s get to the whole Larry Counts thing. You remember what I told you over the phone—

Randy Swick: Yes.

Rob D’Amico: Why do you think Larry has such suspicions about you?

Randy Swick: I have no idea. Other than that when Joe Hunt got elected, I ended up taking his job, and he got put back on patrol.

Joe Hunt—one of the Texas Rangers who worked the Shane and Sally case—went on to be sheriff of Tom Green County for a decade in the early 2000s. And Randy says after Joe Hunt was elected, he demoted Larry Counts back to patrol, and hired Randy to take Larry’s old job. So he figures, maybe this all comes down to professional jealousy.

Rob D’Amico: The other thing I think I said on the phone was that Counts said that part of that suspicion was because he said you kept inserting yourself in the case.

Randy Swick: Yeah, there was two people from my city that had been killed. And were missing, and then were found to have been killed. Yeah, I think I should have some interest in it. I think everybody that’s still working this should have interest in it, ’cause it’s still an unsolved case, both for the sheriff’s office and, I’d say, for the PD also. Because those people lived in San Angelo.

Randy had been assigned to juvenile crime in the eighties, and he was investigating rumors of satanic activity. So he knew the teenagers involved in this investigation. And the case file shows he has assisted on the case over the years.

He’s the one who recognized Sally’s driver’s license when it turned up in the police department. And later, when he was with the sheriff’s office and the case was cold, Randy asked the Texas Rangers to step back in to help with an interview.

I ran all of this by Larry, and he told me he’d raised his suspicions before he lost his position under the new sheriff. But he wasn’t the lead investigator on the case. And nothing we’ve seen suggests that the sheriff’s office acted on Larry’s theory.

Nick Hanna has been unequivocal that there is no evidence implicating Randy Swick. But what about another officer?

Larry says the experience with the psychic only bolstered his suspicion that someone with the police was involved. First, there was the crime scene at O. C. Fisher, and how it didn’t show any signs of a fight.

Larry Counts: And if it had just been some—you know, two or three guys showed up out there and started jacking with them, Shane would’ve fought ’em. And as far as we could tell from—there was nothing disturbed in the car or around it. The only other way you could have got him under control was to show up as a police officer. And once you got him handcuffed, then you could control him.

Then, a while later, he heard that two other deputies believed somebody was trying to get rid of the case records, including his report.

Larry Counts: Okay, see—after I left over there, I got a call from one of the detectives asking me about the Shane and Sally case file, because they said they found it in the trash can, and then they got it out. And so this girl called me and said, “Hey, look, I found these files.”

Rob D’Amico: You don’t remember her name, do you?

Larry Counts: Yeah, Andrea Boatright.

I called this detective to hear the story from her.

Rob D’Amico: And the person on the record is Larry Counts, who said that you found, uh, some of the case-file material in the trash.

Andrea Boatright: Yes, I did. I did. Yeah. In a shred box, actually.

One weekend, sometime around 2010, Andrea says she was in the sheriff’s office, processing evidence, when she noticed a cardboard box that smelled of marijuana. She opened the box, and inside she found a jumble of evidence, case reports, and trash.

Andrea Boatright: And it’s just sitting on the floor, and the entire Shane and Sally case is in it.

Rob D’Amico: Wow.

Andrea Boatright: And I’m like, What the hell? Yeah. Yeah. And I’m like, What the hell?

In the box, she found evidence and notebooks from the Shane and Sally case. At the front of one file was a report written by Larry Counts, in which he named three police officers he suspected, and said he feared for his own life.

She didn’t know what to do. She hid the box under her desk and told some colleagues what she’d found. Eventually, she decided to take the box home. Then she called Larry Counts to ask what he thought. After they spoke, she thinks Larry told someone at the sheriff’s office about their conversation. Because not long after, another lieutenant came to her doorstep and demanded she hand over the box.

But I did talk to another former deputy who told the same story. She asked us not to use her name.

Former deputy: I noticed it was in a shred bin forever—like, it said “Shred” on the box, and we passed it—I don’t even know how long it was sitting in there, to be honest, when I was working there. And I think we just got curious. I think it was her and I after hours, and I went through the box, and I was like, “Holy crap, this is the Shane and Sally case.”

In the box, she found Larry’s report about the psychic, and his suspicion that a policeman was tied to the murders.

When we sat down with Nick and Terry last fall, we asked what they thought of this story.

Rob D’Amico: This leads into the most important thing I’d like to talk to y’all about. You know this story, obviously, right?

Nick Hanna: The driver’s license?

Rob D’Amico: No, the evidence next to the shredder, in the box.

Nick Hanna: The version I heard was in a dumpster, I think.

Nick said it seemed strange that Andrea Boatright only told a few colleagues about such a serious breach of protocol.

Nick Hanna: That would be the kind of thing that you’d go right to the sheriff with. You would not fiddle-fart around with a coinvestigator.

Rob D’Amico: Well, I guess the only question then is, I mean—Is this something that warrants another look, particularly because of that incident, or . . . ?

Nick Hanna: Dave Jones—I had a hundred conversations with him about this case before he passed. He never told me this story; nor did Joe Hunt. And I was pretty tight with those guys, so . . . maybe it happened and they weren’t told. I’m just—I don’t have a lot of confidence in the story. Doesn’t mean it didn’t happen.

Karen Jacobs: So you have nothing in the official records of this evidence that was found?

Nick Hanna: No. And it’s pretty reckless to say that—for her to say that.

Terry Lowe: Prior to coming here, I have made cases against police officers in my career, and I wouldn’t have hesitated if something was wrong.

During the search for Shane and Sally’s killers, there were so many times when investigators faced conflicting stories, with no evidence that could point to the truth. This looked like yet another one of those situations, but with an important distinction: this time, the conflict was within the sheriff’s office.

At one point, Nick Hanna called this “the most screwed-up case” he’d ever seen. And as we reported, as we picked our way through the rumors and the alibis, I kept picturing just one thing. One thing that might cut through the noise and finally tell a clear story: that gun that Sally gave Larry Counts.

She told Larry it had been used in a murder in the city, and Larry says he passed the gun to the San Angelo Police. After Sally was killed, Larry wondered if someone in the department was to blame. And when I interviewed Larry Counts last summer, he mentioned a new detail about that gun.

Larry Counts: And they said that they had come across a gun that they were told was used in another murder. So I met them and they gave me the gun. So then, because the gun was supposedly involved in a murder over at the Red Bandana Saloon—a bar down on South Chadbourne—I gave it to the police department, because that was their case.

Not just “a murder in town.” Here was a name: the Red Bandana Saloon. The bar’s owner had been shot and killed in the fall of 1987. And no one has been convicted of his killing.

And there are circumstantial things—dates and details—that suggest a possible connection between these cases. Like, for example: late in our reporting, Nick Hanna sent us a piece of a report written by Larry Counts. It says, “Back in the early part of 1988, when Shane and Sally were talking with me, they gave me a gun. A 25-caliber Raven auto pistol.” That’s the same kind of gun police say was used in the Red Bandana murder.

This fragment of Larry’s report had more, too. Larry had always told us he couldn’t remember who he gave the gun to. Nobody seemed to know. But in this report, he writes, “This gun was given to Detective Massey.”

I hadn’t seen any record that sheriff’s investigators had interviewed him, so I gave him a call.

Larry Massey: It’s been a long time ago, man. I retired in ’99. It’s what, back in ’88?

While I was talking with Larry Massey about the gun, he told me he’d actually met with Shane and Sally, in the spring of 1988, at an overpass east of town called the Bell Street Bridge.

Rob D’Amico: You met Shane and Sally down there?

Larry Massey: Oh, yeah. Yeah.

Rob D’Amico: Okay.

Larry Counts said Shane and Sally had shown him where the satanist group hung out around town. Larry Massey seemed to be describing the same kind of thing.

Larry Massey: But, you know, at the time, wasn’t nothing going on that was criminally involved that we knew of. We were just looking into the satanic, what they were telling us.

So he’d met Shane and Sally. But he didn’t know about this gun.

Larry Massey: I don’t remember anybody giving me a Raven.

At that same time, Detective Larry Massey was actually an investigator on the Red Bandana case. I’ve got a copy of that file. One time, a Raven .25 turned up at a pawnshop, and officers went to get it, to run a ballistics test to see if it was the gun they were after. Which it wasn’t. So it seems like investigators were looking for a Raven .25. But the reports never mention Larry Counts bringing them that same model gun.

The police eventually recovered a Raven .25 that they said did match the evidence at the Red Bandana. I have a report where they noted its serial number. This was on March thirtieth, 1988, not long after Sally gave her gun to Larry Counts.

I’d hoped the Shane and Sally file might also include a serial number, for the gun Sally turned over. If the numbers matched, that could prove the gun that came from Sally had been used in the Red Bandana killing. But according to Nick Hanna, there is no serial number in Larry Counts’ reports. One more piece of evidence probably lost for good.

Karen Jacobs (voice-over): Time is working against this case, in many ways. Witnesses pass away. Memories fade. Evidence gets lost. And Nick and Terry have even less to work with than investigators thirty years ago.

But time also offers one advantage to authorities today, and in the future. DNA analysis was in its early days in 1988. The sheriff’s office still has evidence from the crime scene that might point to Shane and Sally’s killers.

There are Shane and Sally’s clothes, the things they carried in their pockets, and things found near Shane’s Camaro. One item—a piece of cloth that we’re not describing in detail because it isn’t public knowledge—returned DNA from what’s called a “mixed sample,” meaning more than one person. This one has DNA from Shane and from two other people.

Terry Lowe said they got “all the DNA they could” from the suspects. Heath Davis told us he gave a DNA sample “five or six times.” Nick Hanna says they have John Gilbreath’s DNA too.

Steve Schafer is the only suspect listed in case files as having given his DNA, and it didn’t match the mixed sample. As for Jimmy Burnett, it might be possible to collect a sample from his remains in the Philippines.

So we reached out to a Texas Ranger who handles DNA testing for cold cases like this one. His name is Trampas Gooding.

Karen Jacobs: All right. Let me give this a go. Do you hear me all right, Trampas?

Trampas Gooding: Yes, ma’am.

I’d actually met Trampas a few years ago, when I was interviewing Rangers about their work on other cold cases. He’s one of the Rangers’ top experts in DNA analysis, and his work has helped solve a number of sexual assault cases.

Trampas Gooding: I don’t like talking about myself, but there’s more unsolved, that I haven’t been able to solve yet, than I did get solved. So, there’s always more work to do.

Much of Trampas’s work involves sexual assault evidence kits. He’ll work with local law enforcement agencies to test the evidence against DNA profiles in a federal database called CODIS, or try to match the evidence to a family line in a genealogy database—the kind of thing that helped identify the Golden State Killer in 2018.

Today, he said, they’re able to identify a person with just one nanogram of DNA. To imagine a nanogram, Trampas says, picture a paperclip.

Trampas Gooding: If you take that paperclip, stretch it out, cut it into a billion pieces, one little piece is what we’re dealing with. So that is tremendously different from what it was back in the beginning, when DNA first came around in the early nineties.

But, he explained to us that evidence from a case like Shane and Sally’s would be particularly tough to work with.

Trampas Gooding: When they’re outside, the body decomps—decomposes. And so those fluids is actually bad for DNA. It actually kills the DNA that’s there. Even the victim’s DNA is hard to obtain. Then you have the direct sunlight. Then if you have heat, all that affects the DNA that’s there on any particular item.

And Shane and Sally’s bodies, their clothes, everything in their pockets were all sitting in the open, under the Texas sun at Twin Buttes, all summer.

Karen Jacobs: Okay. Well, that explains tons. Thank you very much. I mean, this case, the remains were found four months after they went missing, and they were outside, covered in branches, so . . .

Trampas Gooding: That’s going to be tough. That’s tough.

Along with Trampas, we spoke to people at private labs that work on cold cases like this. One mentioned a new technology called the M-Vac that can extract DNA from surfaces that wouldn’t have yielded a good sample before. There’s also that hair that Terry Lowe found on Shane’s boot. In 2016, Terry had it sent to a lab that, he says, wasn’t able to find anything useful. We talked to a DNA expert who told us the way labs analyze hair today is far more advanced, and investigators could have a lab take another look. Ultimately, they agreed with Trampas that making a match in this case would be a long shot, but with all these advances, it wasn’t entirely out of the question.

Here’s Trampas again:

Trampas Gooding: No, it’s not magic. You know, the uh . . . And it takes the guy investigating the agency; it takes somebody who doesn’t give up. You got to remember why we’re doing this. We’re doing this for the victim and their families. And so, you got to stay at it. Even when all leads are exhausted, you might set that case aside but go back and revisit it every once in a while. Relationships change. Somebody might have some information that didn’t provide it in the past. And if you don’t go knock on their door and see what they have and if that’s the right time to talk, shame on us.

Rob D’Amico (voice-over): So where does that leave us, after all we’ve learned about this case?

Solving this case will either take powerful new testimony from credible witnesses or some piece of physical evidence that ties a suspect to the murder. And if that evidence exists, there is one new investigative unit that could be capable of finding it.

Sally’s stepdad, Bill Wade, told me about this possibility one day last summer. In 2021, the Texas attorney general’s office opened a Cold Case and Missing Persons Unit—a small team of investigators, backed by experts in forensics and DNA analysis. Bill wondered if they might be able to help.

So I reached out to the senior counsel at this new cold case unit, Mindy Montford. She told me that to consider taking a case, they’d need a request from the investigating agency—in this case, Sheriff Nick Hanna’s office.

Montford told me that when her unit takes a case, they start from scratch. They send in investigators to look at every case file, every note scribbled on a piece of paper. They even reinterview sources. It’s an exhaustive process.

But she was honest with me. She said the unit already has more cases on its plate than it can handle. Still, she said this case was intriguing, particularly the chance that her unit could help with the DNA sample from the crime scene. Last I heard, her office was reviewing whether they could take the case.

This spring, a couple weeks after Sally’s birthday, Pat and Bill Wade came in to talk to us. We talked about how they felt about the investigators’ work on the case so far, and what they hoped authorities could do from now. And it was a reminder that—as challenging as this case has been for them, and still is—giving up isn’t an option.

Bill Wade: You know, I haven’t had any complaints about law enforcement’s involvement since David Jones took over as sheriff.

Pat Wade: And Terry Lowe worked so hard. I mean, he just wanted to solve this case so desperately.

Bill Wade: You know, David Jones, Terry Lowe, Nick Hanna—those guys have been bulldogs on the case, and I can understand their frustration with having to run every lead down that they’ve got. Pulled people in, talked to ’em multiple times, done lie detector tests, done DNA, and nothing is enough to get it over the finish line.

Pat Wade: But I want this resolved. I want to know the answers. And I promised her that I would never let go of it, and I would still seek the answers to it, and I don’t intend to. The years have . . . Look how much older I am now than I was when all this started. But I’m still as committed now as I ever was. I just don’t think it’s fair for those kids to never have any justice.

I also went back to San Angelo to visit Marshall again. We took a ride around town. I wanted to see how he was doing, and talk about what comes next for him. Because, for Marshall, Pat, and Bill, this story isn’t just about the past. Every day adds a little more.

We drove by Steve Schafer’s old house.

Marshall Stewart: That used to be the thing back in the fifties and sixties—a lot of rock houses were built. My grandpa on my dad’s side, his dad did a lot of the rock houses in town.

And I mentioned the report we’d seen that confirmed the gun Shane and Sally turned over had come from Steve Schafer.

Marshall Stewart: That’s what I thought. That he was the one that passed it on to her. And then when things started turning bad, they were getting scared and wanting out, then she knew she had to get rid of it.

On our drive, we stopped by the Bell Street Bridge, where we’d heard Shane and Sally met with San Angelo police.

Marshall Stewart: It’ll be interesting to see if they’ve actually gone in there and removed a lot of that graffiti, or if the new people have gone in there and tagged it or something.

Nick Hanna was interested in what Shane and Sally had provided as informants, but the records from the time offer so few details. It fed into the frustrations Marshall has felt about law enforcement since the day Shane and Sally went missing. That for all the talk about unreliable witnesses, and conflicting alibis among the teens’ social group, there were gaping holes in the investigative record too. Missing reports that could have made it clear what really happened.

Marshall Stewart: Yeah. When you go to a location to meet somebody, and you’ve got that detective mindset, or should have it—whether you go back and document it like you’re supposed to, that should stick. I mean, I can go back to places where I met the other kids and we talked, and I can go back to the neighborhoods and get close to the houses where I went. I don’t know if my mind’s a little bit sharper that way, but to be law enforcement and not document, and not keep it fresh in your mind, I don’t understand it.

And the fact that officers who received a potential murder weapon from Sally managed to lose track of the gun—and its serial number—entirely.

Marshall Stewart: That just blows my mind. Something that critical—Sally being so terrified and trying to get rid of that gun and turning it in to law enforcement.

On the ride, I asked Marshall what he’d hope for from the sheriff’s office today, and in the future. What he wants is the same thing Bill and Pat Wade want: to hear from investigators that they’re serious about finding out what happened to their children.

Marshall Stewart: If I were the head of law enforcement, I would at least tell my main detective, “You need to go talk to the parents of the kids. Let them know we’re working on this case. It’s not just sitting in a cardboard box waiting for somebody to come in and confess. We need to be out there pushing to get some answers.”

Pat Wade: What else can we do? I don’t see a lot of options there. We have to depend on the people that investigate the crimes.

Bill Wade: I think it’s really about getting the answers, and making sure that the people responsible are held accountable for it.

Marshall Stewart: From the parents’ role, sitting here, what I see is, everybody that may know something is dying, and the answers are dying and falling away. And so what do you do with it? That’s the hard part of living with something like this.

Bill Wade: The term “closure” gets tossed around, but it’s not really about closure, because when you say, “How do you cope,” well, you cope with the emotional damage and the scar tissue it leaves the same way you cope with scar tissue left by any kind of permanent injury—you work around it. You live around it.

Pat Wade: I mean, there’s a part of you that goes on. I mean, I’ve had a life. But there’s a big part of me that died when Sally died. I’m not the same. You know, I spend a lot of time now with rescue animals, and I raise flowers and roses, and I do things like that, but . . . I don’t think I survived it, quite honestly.

Marshall Stewart: You want to love your kid forever. You want ’em to be with you forever. But once they pass on, the only thing you can take forward from them is the love that you had for ’em and the good times that you shared.

Bill Wade: What I’m hearing from Sheriff Hanna is, it’s not a lack of funding; it’s a lack of productive leads to pursue that can close the case.

Marshall Stewart: That’s what it takes to resolve a case. Somebody with initiative, and somebody with a desire to say, “The answer is here. We just need to get to it.”

Bill Wade: Let’s get this cold case prosecutor unit to take another look at it and say, “Okay, is there enough there to prosecute? What’s it going to take to get this into court and win?”

Pat Wade: So it can be solved.

Karen Jacobs: I think so.

Pat Wade: I just feel like it can.

Karen Jacobs: Yeah.

[phone ringing]

Mindy Montford (recording): Hi, this is Mindy Montford. I’m not available to take your call. Leave a message. I’ll get back with you as soon as I can.

Marshall Stewart: Hello, Mindy, it’s Marshall, Shane’s dad, out in West Texas. Just giving you a call to see if there’s any updates or information, any details, or what you’re working on, that might be pertinent to our case. Just appreciate anything you can share with me. I know you guys are loaded up there. Please just give me a call. Anything you can share. Thank you.

- More About:

- San Angelo