Along the back wall of Pico de Gallo restaurant, in downtown San Antonio, beyond the cases of pan dulce, looms a colorful, 33-foot mural painted by local artist Armando Sánchez in the style of da Vinci’s Last Supper. It depicts 74 notables, virtually all of them Hispanic, including Medal of Honor recipient Roy Benavidez; civil rights icon Dolores Huerta; Tejano singer Selena; and Willie Velasquez, the founder of the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project.

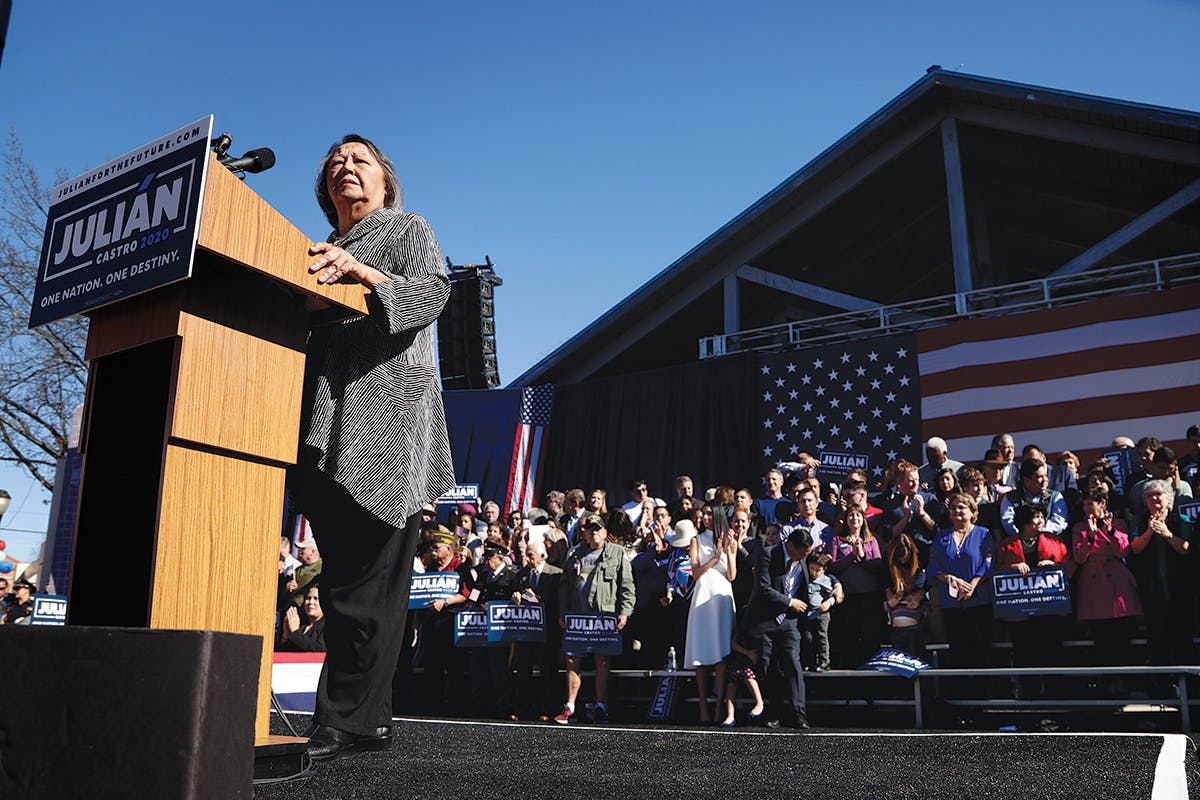

The viewer’s eye is drawn to the center of the mural by the image of la Virgen de Guadalupe, Mexico’s most revered religious figure, who hovers over the only family depicted in this painting: the Castros. Just beneath the Virgin is the image of Maria del Rosario “Rosie” Castro, to whom the artist dedicated the mural, in 2013. On the table in front of her is a framed picture of her late mother, who emigrated as an orphan from Mexico to the United States. But the focal point is Rosie, whose reputation as a longtime community activist understates what is arguably her most significant contribution to San Antonio and to America. Flanking her in the mural are the two figures who may turn out to be her greatest legacy: her twin sons, Joaquin, a U.S. congressman who by all appearances is gearing up to challenge John Cornyn for his Senate seat, and Julián, the former mayor of San Antonio and a current candidate for president. Together, the two men personify the political hopes of millions of Hispanics, who make up one of the fastest-growing demographics in this country.

It’s early at Pico de Gallo, a gathering spot for politicos, and months before Julián would invoke his grandmother’s journey and his mother’s passion for politics as he declared his candidacy for president. I take a table close to the mural, and as I’m scanning it to see how many faces I recognize, the painting’s dedicatee quietly walks up behind me and introduces herself.

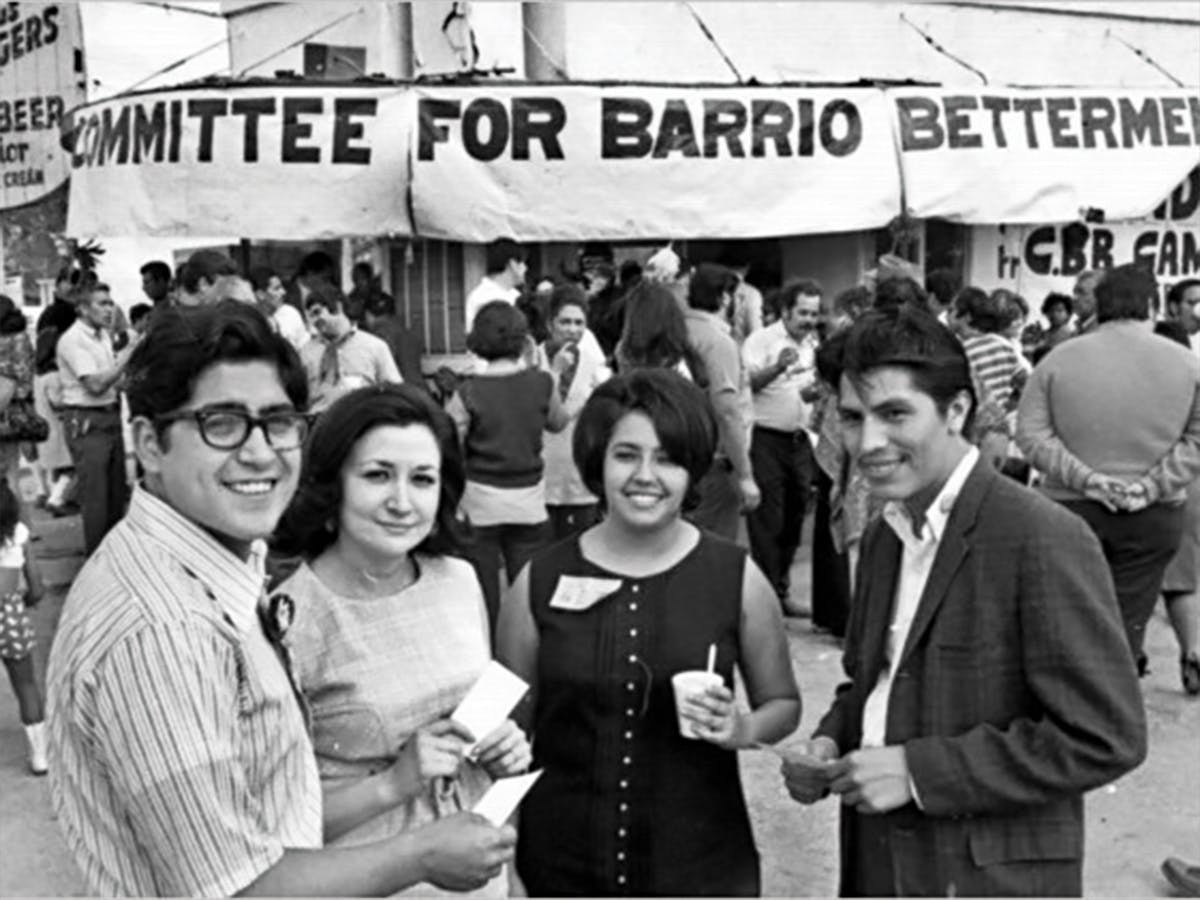

At this hour, there are few patrons in the restaurant, but our waiter immediately comes over, a look of recognition on his face, to warmly greet her as she takes a seat. She’s dressed casually in a pantsuit and, at 71, has the appearance of someone at ease in her retirement following a long, often contentious career in politics and education. Rosie isn’t as well-known as her sons, but in this town she forged her own path as an activist for Hispanic opportunity and representation. She employed a fierce and outspoken style, as was appropriate, she says, for a different time—one when it was not uncommon throughout the Southwest to see stores with signs that read “No Dogs or Mexicans Allowed.” That attitude was pervasive, even among city leaders. In 1970, when she was in her early twenties, Rosie and a group of fellow activists were arrested while picketing the San Antonio Savings Association, which was owned by Mayor William McAllister, who had said of the city’s Hispanic population, “They’re home-loving. They love beauty. They love flowers. They love music. They love dancing. Perhaps they’re not quite as, uh, let’s say, ambitiously motivated as the Anglos are to get ahead financially, but they manage to get a lot out of life.”

Rosie spoke vividly about the historic figures depicted on the mural next to us. Most were friends. Many were rivals. All were indelible forces in creating that moment in January when, less than two miles away, in Plaza Guadalupe, her son would declare his candidacy for the presidency.

Conventional wisdom suggests that Julián, who has failed to gain much traction in the large field of candidates vying for the Democratic nomination, should exhibit more of his mother’s provocative personality—the sort of forward character that has boosted Elizabeth Warren’s and Bernie Sanders’s campaigns. Such wisdom also suggests that he should pick an issue or two and own them—as his mother did and as several of his competitors have done. Warren is best known for advocating for tough regulations on powerful corporations and higher taxes on the wealthy, Sanders for free college and Medicare for all. But Julián—like his fellow Texan, the sunny and platitudinous Beto O’Rourke—didn’t claim such an issue during the first months of his candidacy. He’s someone who has long shied away from risk-taking in his rhetoric, his policy prescriptions, and his career moves. In 2014, for example, he was widely criticized for not running against Governor Greg Abbott in the afterglow of his 2012 keynote address at the Democratic National Convention.

Instead, as the only Hispanic in a large Democratic field, he is striving to position himself as the best candidate to rally voters who recoil from Trump’s nativist policies and Twitter rants. He presents himself as a calm, pragmatic, inspiring example of an America that embraces diversity and offers opportunity to all who will work to seize it. He is, on the surface, the opposite of his fiery mother.

But they are connected by intellect and strategic savvy. She is the most influential figure in her sons’ professional lives; she is never among their public critics. Their differences from her—in terms of style, in terms of tactics—aren’t a form of rebellion or a disavowal of her life. They’re very much a means of continuing the work she started five decades ago. And Rosie Castro wouldn’t have it any other way.

Rosie’s politics reflect her hardscrabble upbringing in San Antonio at a time when opportunities for Mexican immigrants and even Hispanic citizens were few and prejudice against them was often openly expressed. Her mother, Victoria, immigrated as an orphan at about age six and left school after third grade. When she became pregnant with Rosie, in her early thirties, the father of the child abandoned them. After Rosie was born, Victoria went to work cleaning homes in the wealthy neighborhoods of Alamo Heights and Terrell Hills, on the city’s near North Side, and often took her young daughter along. On at least one occasion, described in Julián’s recent memoir, An Unlikely Journey: Waking Up From My American Dream, Rosie was so offended by the disparities in wealth between the neighborhoods her mother worked in and the part of town they lived in that she threw rocks at the residents’ fancy cars.

Most of the time, however, Rosie entertained herself by reading. Although Victoria had dropped out of elementary school, she taught herself to read and shared that love with Rosie, who developed a special affection for poetry; years later, she would name Joaquin after “Yo Soy Joaquin,” a poem by the Chicano-rights activist Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzáles. On those occasions when Rosie stayed home as a latchkey kid, she began to learn the subtle art of community organizing. She was forbidden by her caretaker, who worried about her safety, to visit the homes of neighborhood kids, so she persuaded them to come to her house by creating clubs and community projects. “One time we decided that we would build a swimming pool at my house,” she remembers. “We thought it was easy. You just dig a big hole and put water in it.”

Rosie spent twelve years attending Little Flower Catholic School, where she began questioning authority, much to the consternation of the nuns who ran the place. It began innocently enough during her elementary school years, with small shows of defiance. But by high school the relationship between the administration and the rebellious student became more adversarial. “I was editor of the paper, and almost every elected position there was to have, I would win it,” Rosie said in an oral history recorded in 1996. “Whenever it was appointed by a nun, I never got it.” Her growing interest in politics, she said, was often seen as unseemly for a young woman. She graduated from high school as class valedictorian, which earned her a scholarship at the nearby Our Lady of the Lake College.

There, Rosie’s interest in politics grew, and she petitioned the administration to let her organize a Young Democrats club. The administration agreed, with one proviso: there had to be a Young Republicans club too, so Rosie helped organize that as well. As a young activist she made at least one high-profile public appearance: she testified before a Texas Senate subcommittee, arguing in favor of lowering the state’s voting age from 21 to 18—an idea that had broad support as more and more 18-year-olds fought and died in Vietnam. (This change finally happened in 1971, when the Twenty-sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution became law, with Texas voting in favor.)

During that period, at the nearby campus of St. Mary’s University, students founded the Mexican American Youth Organization, a group that focused on promoting voter registration and combating suppression of Mexican American voters. As the group traveled through South Texas, registering voters, they inspired Mexican Americans to run for local school boards, and several won, integrating many of the boards for the first time.

The Chicano movement in Texas had begun in earnest, and Rosie became one of its leaders. At the time, even many Mexican Americans viewed identifying as a Chicano or Chicana as controversial. Prominent San Antonio congressman Henry B. González, for one, regarded it as at odds with the long-held goal of assimilation. “The struggle wasn’t always so much on the outside as on the inside,” Rosie says. To come out as a Chicano or Chicana was initially to confront one’s own family. “I certainly got it at home,” she says. “Some cousins said, ‘You’re ruining it for everyone.’ ”

Rosie remembers one local columnist who routinely argued that the Chicano movement represented reverse racism and referred to its activists as “militants.” Compounding this pressure on her was the administration at Our Lady of the Lake, who called her family to warn that she was turning radical. Her vocal support for Angela Davis, then a member of the Communist Party USA, brought Rosie to the attention of the FBI.

Just before her graduation, in 1971, Rosie decided to seek election to the San Antonio City Council, which at the time required all candidates to run citywide rather than in specific geographic areas, known as single-member districts. Rosie knew that as a citywide candidate taking on well-funded opponents from the city’s Anglo North Side, she didn’t stand a chance. But she regarded the campaign as a bully pulpit that would help her point out inequities such as poor flood control on the city’s largely Hispanic West Side and the dearth of Latino representation in the upper echelons of city government and the police department.

As expected, she lost. But her campaign is widely credited with forcing the city to take seriously the notion of electing council members through single-member districts. After the loss, Rosie was approached for comment by a local reporter. She declared, “We’ll be back.”

Mario Compean, in 1971.UTSA/San Antonio Express-News via ZUMA Press

That defeat marked the beginning of a new level of political activism for Rosie, manifested through her work with Partido Nacional de La Raza Unida, also known as the Raza Unida Party, which she joined when it formed in the early seventies. Because of intensive voter registration campaigns, many West Siders, including Rosie’s mother, had cast their first ballot in the 1971 city council race. Their candidates didn’t win, but organizations such as the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund noted that, had San Antonio used single-member districts, the outcome would have been much different. Chicano groups also launched campaigns against Texas congressional and legislative district lines that appeared to discriminate against Mexican Americans. After a series of U.S. Supreme Court rulings and an expansion of 1965’s Voting Rights Act, San Antonio voters decided in 1977 to elect their council members through single-member districts.

Rosie had risen to the position of Bexar County chair of Raza Unida when she became romantically involved with Jesse Guzman, another community activist, who educated teachers about Chicano history and culture. Guzman was married and had five children, but soon he and Rosie found out that she was pregnant. Rosie was hardly in a good position to raise a child (much less the pair of children she soon learned she would have); in addition to the fact that she was unmarried, her association with Raza Unida rendered her essentially unemployable. According to one friend, soon after Rosie became pregnant, a thief broke into her home and then, seeing how few possessions she had, left without taking anything .

She had one small spot of financial good luck, though. On September 15, 1974, her mother won $300 in a menudo cookoff. The next day—September 16, Mexican Independence Day—Rosie delivered the twins one minute apart. The proceeds from the cooking contest helped pay some of her medical bills.

Guzman moved in with Rosie and their new twins, as did Rosie’s mother, whom the boys called Mamo. “My brother and I recall an essentially normal family environment, but it must have been surreal for all the adults involved,” Julián wrote in An Unlikely Journey. “My father had a wife and five children living across town, whom he still occasionally saw.

“When Joaquin and I were around five they started taking us to these meetings, which blended activism and partying,” Julián wrote. “They drank and laughed and organized rallies and voter-registration drives as Joaquin and I entertained ourselves at the pool table or with the jukebox . . . From an early age, Joaquin and I were taught the importance of political engagement, and we attended rallies and were even pictured in some of the campaign literature. By the age of eight, I lost count of how many times I heard my mother tell me, ‘As a citizen, you need to participate in the democratic process. If something is wrong, you can change it. Your efforts may pay off in the long run, even if you don’t get your way right now.’ ”

Guzman moved out when the twins were eight—he stayed distantly engaged in their lives thereafter—and the family’s perilous finances grew even tighter. Once, Julián told Rosie that a classmate had made fun of his clothes. Rosie reminded him of the number of stars posted next to his name in the classroom, for academic achievements. She asked him how many the classmate had. None, Julián responded. “That’s what is going to count,” she said.

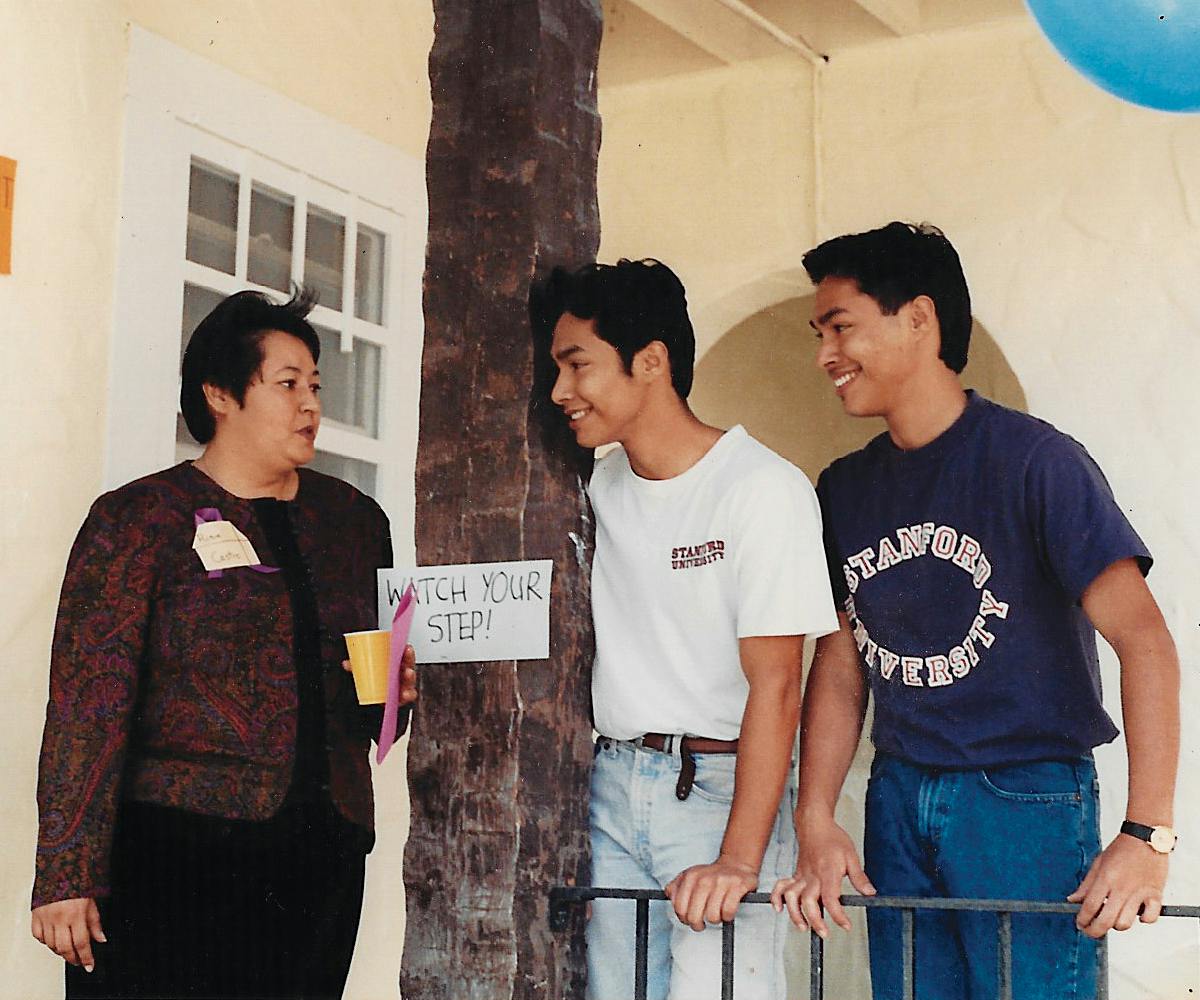

The twins were exceptional students and enthusiastic athletes in football, basketball, and tennis. They graduated a year early from high school and won small scholarships and took out loans to attend Stanford University, where classmates remember them as always neatly dressed and polite. Julián worked as a White House intern during the Clinton administration in between his sophomore and junior years, and then both brothers went to Harvard Law School. After graduation, they went to work for the San Antonio branch of the prestigious Akin Gump law firm.

It was a trajectory far, far from Rosie’s, and this was no accident. During the boys’ childhood, Rosie’s political life changed significantly. The Raza Unida Party, which had been the center of her activism, began to disintegrate. Competing strategic visions about the direction of the party created fissures, as did much of the party’s rhetoric and many of its tenets. Key among them was the concept of a mythical place in the Southwest called Aztlán. “There were different ways of looking at it,” Rosie tells me. “The idea was to create a space in this community that showed respect for Latinos and the ability to have the rights we deserved. It was not a land grab of the entire Southwest. We were creating, we hoped, a born-again nation with the understanding of Latinos.”

But some members of Raza Unida saw the movement in strictly racial and nationalistic terms, limiting its appeal to a broader public. Though the party had some victories at the local level, its attempts to run statewide came to little. In 1972 Ramsey Muñiz, a graduate of Baylor University’s law school who had also been a popular football player for the school, ran for governor, and despite an aggressive campaign, he received only 6 percent of the vote. Disappointing as it was, that was a high-water mark for Raza Unida’s political ambitions. By the late seventies, when the Castro twins were still young, the party unofficially dissolved.

Rosie acknowledges that her experiences with Raza Unida influenced the way she raised her sons. “I tried to encourage cooperation—that if you achieved, we all achieve,” she says. “Whenever I talked about the Raza Unida Party, I talked about how I could have done things differently, done this better.” If her sons were going to finish the fight she had started, they would have to do so in a very different way than she had.

Exactly thirty years after Rosie’s 1971 city council defeat—after which she declared, “We’ll be back”—Julián, whose political ambitions were no secret, was elected to that same city council. He won 62 percent of the vote and became, at age 26, the youngest council member in the city’s history. And there were bigger things to come. He narrowly lost a mayoral bid in 2005 but then won in 2009 and was reelected in 2011 and 2013. As mayor, he worked to build coalitions between mostly Anglo business leaders and advocates for the city’s Mexican American community. His signal achievements were a newly vibrant downtown and the passage of a voter referendum that funded expanded pre-K education. He advocated for gay rights as well as balanced budgets.

In 2012 he became the first Hispanic to deliver a keynote address at the Democratic National Convention, and in 2014 he resigned as mayor to become the United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. And in every position he has held, he has been known for almost never losing his temper or otherwise showing strong emotions.

“It’s something the boys learned directly from their mother,” says Blandina “Bambi” Cardenas, the former president of University of Texas–Pan American (now Rio Grande Valley) and a close friend of the Castros. “If you listen to both of them, you will always hear a reasoned and informed position. They are well-read, and yet there’s that connection to practical politics. And Rosie, she’s an intellectual. She likes poetry. She reads constantly, and yet she’s rooted in the barrio.”

There are times when, for all the relative serenity Rosie seems to have cultivated late in life, the barrio fighter in her makes an appearance, and you can’t help but wonder how much it has cost her to raise two boys with instincts apparently different from her own. “Don’t confuse my politics with the politics of my sons,” she tells me. “I hate when people do that.”

As he began his campaign for president, Julián showed no interest in changing how he has always handled himself. Unlike his mother, who admits to drinking heavily during difficult periods in her life, he’s a teetotaler, and he says that his discipline flows from a belief that he has little room for error. “I didn’t grow up with the skin color or the background where you normally get a second chance or you get to fail upward,” Julián says. “I’ve always tried to be thoughtful about what I’m going to do because I’ve had to be. If I’m elected president, I’m going to be just as thoughtful about what our country will do in the years to come.”

“A politician has to know when the time is right,” Rosie says in defense of her boys’ caution. Her sons, she says, “have their own sense of timing. I can see the depth of [Julián’s] politics. He has the intellectual capacity to know when the time is right. I wish that he didn’t keep getting underestimated that way.” The pragmatist in her, for example, dislikes the criticism that he was afraid to run for statewide office against Abbott five years ago and again last year. She cites the large margins that Abbott’s Democratic opponents Wendy Davis and Lupe Valdez lost by as evidence that both races were suicide missions.

A presidential campaign, the family has apparently decided, is not—though there will be plenty of challenges. Julián and Rosie have a good sense of the lines of attack that will come their way if his campaign takes off. In 2010 she was savaged by conservative media after she told a writer for the New York Times Magazine that the defenders of the Alamo were “a bunch of drunks and crooks and slaveholding imperialists who conquered land that didn’t belong to them. But as a little girl I got the message—we were losers. I can truly say that I hate that place and everything it stands for.”

While such sentiments offend many Texans and are seldom spoken publicly, they’re fairly common among Mexican Americans in Texas and are similar to the attitudes of many black Americans toward the Founding Fathers who were slave owners. (When asked about his opinions on the Alamo, Julián calmly cited the importance of the Alamo to the San Antonio economy as a major tourist attraction. He explained that his generation is “less burdened” by history than that of his mother.)

The family got another bitter taste of backlash in 2012, when Julián delivered the keynote address to the Democratic National Convention. Critics reached back forty years to Rosie’s involvement in the Raza Unida Party. Though she was not one of the members who advocated the creation of a separate Hispanic nation, she and her sons were deemed guilty by association. On the day of Julián’s keynote speech, the conservative Breitbart News Network website published a story headlined “Julián Castro: A Radical Revealed.” It stated, “Their mother Rosie helped found a radical, anti-white, socialist Chicano party called La Raza Unida (literally ‘The Race United’) that sought to create a separate country—Aztlán—in the Southwest.”

But none of that has dissuaded Julián from going forward with his campaign. And in April, he showed that he had a little bit of Rosie’s fire in him. Perhaps motivated by the fact that his candidacy was polling at one percent, on April 2 he unveiled an immigration platform that went well beyond supporting Dreamers and opposing family separation: he called for tossing out the nearly century-old law that makes illegal entry into the country a federal crime. Though this was not a call for “open borders”—entering the country without papers would remain a civil crime—it was a bold and controversial move. It was his Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren moment—though the inspiration for sticking his neck out may have been located closer to home. Just as Rosie will defend her sons’ reserve and pragmatism, Julián makes no apologies for his mother’s militant past. “There was nothing radical about it,” he says. “Raza Unida was trying to run candidates for office. That is the apex of American democracy.”

As is, he might have added, having your son run for president.

This article originally appeared in the May 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Mama’s Boy.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Julian Castro

- San Antonio