In November 2010, as he was readying for his second term as Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives, Joe Straus invited Midland oilman Tim Dunn to breakfast. It was an attempt, after a bruising election season, to extend an olive branch. Dunn had helped bankroll the tea party surge in Texas, and an organization he started, Empower Texans, had attacked Democrats and participated in rallies across the state protesting property taxes and excessive government spending. Straus, a San Antonio businessman from a well-off Republican family, had been chosen as Speaker in January 2009 by a coalition that comprised GOP fiscal conservatives like himself and all the chamber’s Democrats.

But in the 2010 election, the Democrats lost 24 seats. Dunn, in other words, had done much to shrink the Speaker’s base of support. Nevertheless, Straus regarded himself as fiscally responsible and thought he and Dunn might find common ground on that subject.

With plates of eggs before them, Dunn and Straus sat at a table in the Speaker’s Conference Room, surrounded by dark pecan paneling, Audubon prints, and photographs of Straus family members posing with George H. W. Bush (a friend of Straus’s mother) and U.S. senator John Tower. Dunn never lifted his fork. He didn’t seem interested in hearing what the Speaker had to say. But he did have an agenda. He demanded that Straus remove a significant number of committee chairs and replace them with tea party activists supported by Empower Texans. Straus refused. Then the conversation moved on to evangelical social policy, and, according to Straus insiders, Dunn astonished Straus, who is Jewish, by saying that only Christians should be in leadership positions.

After the meeting, a stunned Straus told aides that he had never been spoken to in that way. Though Straus’s aides considered the statement anti-Semitic, it was more likely an expression of Dunn’s pro-evangelicalism. In sermons and other public statements, Dunn has asserted a belief that born-again evangelicals who follow biblical laws are graced by God and given a duty of political leadership. “If you are an evangelical and you don’t vote, that means you are not doing your duty because you are the ones that God gave the authority to,” Dunn once said.

“The real biblical approach to government is—the ideal is—a kingdom with a perfect king,” Dunn told a Christian radio audience in 2016. (Dunn begins speaking 58 minutes into the video.) “But pending that, yes, the ideal is a self-governing society.” Dunn’s notion of self-government, though, is different from that of most Americans. He has stated repeatedly that our democracy must be brought into line with biblical laws. When secular governments stray from the Ten Commandments and try to make their own rules, he says, “you have a false perfect government with a false messiah.”

Dunn is probably the most influential donor operating in Texas today. Since 2002, he has given at least $9.3 million in publicly reported campaign donations to Texas politicians. Federal candidates and super PACs have received $3.2 million of Dunn’s money since 2010. Quite likely, a similar amount of his money has flowed in obscurity, through a maze of nonprofit foundations, some of which he controls and many of which hide their true identity and never report their donors.

The driving ideological forces behind Dunn’s organizations are small-government libertarianism and a socially conservative agenda, the latter of which has been embraced by the tea party in Texas. (While the tea party began as a protest against big government and certain Obama administration programs, as early as 2010 Texas tea party groups had started to morph into vehicles for socially conservative activism.) It wasn’t long after Dunn and Straus met for breakfast that tea party–style conservatives around the state started sending out emails and press releases pushing for a House leader who was both right-wing and a Christian; as one member of the State Republican Executive Committee put it in a private note to another member of the committee, “We elected a House with Christian, conservative values. We now want a true Christian conservative running it.” Whether the email campaign was spontaneous or coordinated remains unclear. In an interview with the Texas Observer, Empower Texans’ director, Michael Quinn Sullivan, called the emails “vile and disgusting.” But he also seemed to take a swipe at Straus. “I’ve never heard anyone talk about Mr. Straus’s religion,” Sullivan told the magazine. “There is no place in the speakership race for discussions of people’s religion or lack thereof” [emphasis added].

Dunn is a powerful figure in the ongoing struggle for the soul of the Republican party, a fight that has been waged for years between the fiscal conservatives who built the modern party and the social conservatives who want to claim it. He is rarely the public face of these efforts, preferring instead to use his money and influence behind the scenes. For more than a decade, Empower Texans—which encompasses a political action committee and two foundations, all named Empower Texans—has challenged Republican incumbents in party primaries, often using questionable methods to sully its targets’ reputations.

During the 2014 elections, the Empower Texans PAC spent $4.7 million to affect state elections, including almost $2 million in loans and contributions to two candidates, now Attorney General Ken Paxton and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick. While Dunn’s allies have yet to seize control of the House, their takeover of the Senate Republican Caucus empowered Patrick to prioritize gender-specific bathroom legislation over public school finance issues and property tax reform.

But in the 2018 primaries, Empower Texans’ tactics triggered a backlash. Even the conservative website Breitbart had by then soured on Dunn’s operations, likening his grip on state politics to “a Russian oligarchy situation where you have a billionaire who doesn’t even live here choosing who’s my leader because the guy didn’t kiss his ring.” Payback came from conservative business leaders across Texas who were worried that Dunn’s agenda was bad for the Texas economy. They poured more than $3 million into defeating most of the legislative candidates backed by Empower Texans and its ally, the antiabortion group Texas Right to Life. But Dunn is undeterred, because he believes he has a duty to God.

“Nothing comes easy to West Texas,” former first lady Barbara Bush once said of living in the Permian Basin. “Every tree must be cultivated, and every flower is a joy.” It’s a harsh environment where sand creeps under the barbed-wire fences and across the roadways, ever threatening to erase civilization. Here, the fleeting nature of life is evident and religion blooms. But beneath the brown desert lies an ancient seabed containing some of the richest oil and gas deposits on earth. Oil is the reason people live there. With each boom, the roughnecks and geologists and petroleum engineers come; with each bust, most of them leave. The oilmen remain, having converted some of those fossil fuels into gold.

Amid this austere landscape, Dunn embraced evangelical faith and made a fortune financing wells to extract oil that he once told a British journalist was deposited beneath the earth’s surface by God a mere 4,000 years ago, not the 200 million years as determined by earth science. He has been through boom and bust and has joked that Midland is “the easiest place to lose money that you can ever imagine.”

By all accounts, though he is sometimes filled with a sense of self-importance, Dunn is an affable man, and his sense of humor often turns into jokes made at his own expense. At 63, he is tall and lean, with a long face dominated by a strong jaw and prominent chin. When he sweeps back his straight silver hair, he has the look of someone who might have been a surfer in his youth, if only there had been someplace to surf on the plains of West Texas. An intellectual and amateur theologian, he is at ease quoting Plato or the Apostle Paul.

The youngest of four boys, whose father was a Howard County Farm Bureau insurance agent, Dunn grew up in Big Spring, about forty miles from Midland. In high school he was an Eagle Scout and a guitarist in a rock band. He left home to study chemical engineering at Texas Tech University, where he met his future wife, Terri. They married in 1977, at the end of their junior year, and eight months later she was pregnant with the first of their six children. Dunn went to work for Exxon, then spent several years working in commercial banking. The family moved to Midland, where he worked at a bank before joining Parker & Parsley Petroleum as director and, eventually, chief financial officer. There, his deep involvement in the two anchors of Midland’s stark culture—the oil business and evangelical Christianity—would spur him to political activism.

Already on a path to wealth, Dunn formed his own oil and gas company, now known as CrownQuest Operating LLC, in 1996, with wells in Texas, New Mexico, and Utah. As a privately held company, CrownQuest doesn’t have to make its financials publicly available, but over the years it has clearly done quite well; the Texas Railroad Commission lists CrownQuest as the thirtieth most productive Texas oil company in 2017, having produced 6.6 million barrels of oil that year. At the average price of West Texas Intermediate crude for the year, that would translate into about $335 million in gross revenue.

Dunn’s business career has informed his libertarian thinking. At Parker & Parsley, he oversaw securities transactions that were subject to plaintiff lawsuits, an experience that made him a strong supporter of tort reform. At CrownQuest, he has fought against limits on methane emissions and the potential listing of the dunes sagebrush lizard as endangered, a designation that would have halted drilling in parts of West Texas and eastern New Mexico.

In 2006 he opposed a Texas tax reform proposal to cut property taxes and offset those losses by expanding the state business tax to include partnerships, such as those used by doctors, lawyers, and oil companies that finance wells through investors. He showed up at a hearing of the Texas Tax Reform Commission in Midland and presented a 22-page report in which he argued that school property taxes could be not just reduced but completely eliminated in seventeen years. He asserted that this could be done without raising business taxes if the state increased its share of spending on public schools by drawing on surplus state tax revenue and restricting spending increases to no more than what was needed to keep up with population growth and inflation. Legislators passed their own proposal, but Dunn’s idea became dogma for conservative property tax opponents. The Texas Public Policy Foundation, a conservative think tank where Dunn serves as vice chairman, is pushing the Legislature to adopt a version of the plan when it meets in 2019.

It’s not clear what impact the 2006 tax reform has had on CrownQuest; oil production companies and royalty owners were hit with new tax payments, but these were supposed to be offset by cuts in the taxes paid on oil and gas properties. (In 2017 CrownQuest owned more than $2 million in taxable real estate in five West Texas counties.) When the tax reform passed, Dunn was unhappy that the new business tax had been negotiated—as he saw it—behind closed doors by lobbyists doing what was best for their clients rather than the citizens at large. In short, interest groups had a seat at the table. It was then that he formed Empower Texans, giving his director Sullivan a clear directive: “I don’t want you to get a seat at the table. I want you to get rid of the table.”

But though it was born as an anti-tax organization, Empower Texans would soon advocate for socially conservative positions, in keeping with the evangelical religion that has been the other pillar of Dunn’s worldview.

In the Permian Basin, the old saying is that you raise your family in Midland and raise hell in Odessa. The oil field roughnecks have traditionally lived in Odessa, the executives in Midland. Surrounded by desert, Midland offers few recreational or cultural opportunities outside of church. “I care a lot about family,” Dunn said during a 2016 appearance at the Texas Tribune Festival. “Midland’s a family town—there’s not much else there, work and family.”

Though it was born as an anti-tax organization, Empower Texans would soon advocate for socially conservative positions, in keeping with the evangelical religion that has been a pillar of Dunn’s worldview.

There are more Protestants in Midland than members of any other faith, and evangelicals outnumber mainline Protestants by a factor of five to one. Dunn and his wife attend the nondenominational Midland Bible Church, where the Bible is viewed as inspired by God and without error. Along with several other families, they homeschooled their children; the older ones followed a course of instruction that Dunn created, in which they would read great works of literature and philosophy and then be challenged to square their readings with the Bible. At the urging of friends, in 1998 Dunn turned that curriculum into the basis for the private and unaccredited Midland Classical Academy. “It’s our job to give the kids a faith crisis every day and then lead them to what the true answer is and let them decide,” Dunn says in a promotional video for the school.

For Dunn, the intertwining of libertarian ideas with Christian-conservative ones didn’t start with Empower Texans. His earliest-known foray into state politics, in the early nineties, was joining the board of directors of the Free Market Foundation of Plano, which before that had been called Christian Citizens Inc. Founded by a retired real estate broker named Richard Ford, it was intended to operate as the Texas chapter of Focus on the Family, a national social-conservative advocacy group. During Dunn’s early time on the board, the foundation traveled around Texas, teaching men how to become better parents through Christ and helping physicians practice medicine in a godly manner.

In a recent interview, Ford fondly recalled the time he spent with Dunn. “He is very intelligent. He has a very strong—very, very strong—spiritual commitment,” Ford said. “That’s his total motivation.” Ford said Dunn believes government has improperly meddled in matters of faith and that the country is in spiritual decline.

The Free Market Foundation portrayed itself as concerned with economic liberty but usually aligned itself with groups like the Christian Coalition and the Eagle Forum, opposing gay rights and supporting the restoration of public school–sponsored prayer. Another hallmark of Free Market, which Dunn would later deploy at Empower Texans, was voting scorecards that allowed evangelicals to rate candidates for reelection based on how much support they’d given to social-conservative causes.

But the most significant tactic that Dunn would adopt as his own was that of concentrating on Republican primaries. After the 1998 elections, it was apparent that Democrats were unlikely to win statewide office again anytime soon and that their grip on the Legislature was slipping away. “I felt like the real Achilles’ heel for conservatives was the moderate Republicans,” Ford said. “And so we decided we would go after them.”

In 2002 the foundation’s take-no-prisoners approach ignited a statewide controversy after it targeted six Republican incumbents, including acting lieutenant governor Bill Ratliff, with an incendiary piece of direct mail, paid for in part with a $10,000 donation from Dunn. Because Ratliff had supported including “sexual orientation” in a hate crimes bill, the mailer denounced him as a supporter of “the Homosexual Agenda” and included photos of a man kissing another man on the cheek, a man in a leather bondage outfit, and two men in tuxedos cutting a wedding cake. All six incumbents won reelection, but a year later Ratliff announced his resignation from the Senate. The lesson learned was simple: junkyard political attacks may not work in a single election, but the prospect of such battles scares people off. It’s a long-term strategy that keeps incumbents wondering whether a problematic vote on the floor of the Legislature will draw them an opponent in the next election.

Dunn remained on the Free Market board after a young lawyer named Kelly Shackelford took over Ford’s position and the foundation changed its name to the First Liberty Institute. Under Shackelford, the foundation shifted its focus to coordinating legal challenges to perceived government interference in religious matters. One of its best-known cases in Texas is a court victory that allowed cheerleaders in the small East Texas town of Kountze to paint religious verses on spirit banners for the football teams. Although First Liberty clients have included the Falun Gong and Orthodox Jews, most of them are evangelical Christians.

In 1998, shortly after launching Midland Classical Academy, Dunn joined the board of the Texas Public Policy Foundation, which was founded by James Leininger, an advocate of lawsuit reform and private school vouchers. Leininger, a San Antonio physician turned businessman who, since 2000, has given $10.3 million to conservative Texas candidates and political committees, is the Republican megadonor Dunn bears the most similarity to.

Longtime Texas Capitol observer Harvey Kronberg, the owner of the Quorum Report political newsletter, says that the biggest difference between the two millionaires is that Leininger’s ambitions seem more modest: Leininger wanted to pass private school vouchers, and when his voucher push died in the 2007 Legislature, he started to withdraw from funding Republican primary races. “He was a single-issue guy,” Kronberg said. “With Tim Dunn, it’s a more pervasive libertarian-style philosophy, perhaps an extreme small-government philosophy.” And since the 2010 election cycle, when Empower Texans rallied with local tea party groups, Dunn has been connected to a potent base of activists. “They’ve mastered social networking, and they’ve got a volunteer cadre out there,” Kronberg said. “They’re playing everything from bond elections to school board elections.”

Ever since the rise of the cellphone and internet broadcasts of the legislative session, the gallery of the Texas House has been less crowded with lobbyists than it once was; nowadays, lobbyists can sit in their offices on Congress Avenue and call a member directly if they wish to prompt a vote. But Michael Quinn Sullivan, Dunn’s right-hand man, is often at the Capitol, gathering his legislative allies into a gaggle outside the chamber. He is a lawmaker whisperer, advising members of the House Freedom Caucus—a bloc of hard-line conservatives—on how to vote and what amendments to offer.

At six feet four inches tall, Sullivan towers over most people, though his cherubic cheeks give him a friendly look. As a onetime newspaper reporter and former aide to congressman Ron Paul, Sullivan is a policy wonk and can turn a glib phrase, but he also has a reputation for cynicism and a shameless disregard for fair play. In a riff on his initials, MQS, opponents derisively call him “mucus.” In 2012 Texas Monthly’s Paul Burka wrote that Sullivan would win a contest as the most toxic person at the Capitol and be proud of it.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram columnist Bud Kennedy has been watching Empower Texans for years. He told me that the group is often less interested in major pieces of legislation than in “poison pill” amendments that can be used against incumbents in a future election. “They pick one little vote and say it was against puppies or whatever, and then they blow that up to say that so-and-so hates puppies,” Kennedy said. “It really has nothing to do with whether that person was making good decisions for the future of Texas.”

Empower Texans produces tip sheets telling legislators how to vote, and then, come election time, Sullivan, in collaboration with Texas Right to Life president Jim Graham, produces legislator scorecards to sway voter opinion. The scorecards are so misleading that they have been denounced by the Texas Catholic Conference of Bishops, the Texans for Life Coalition, and the Texas Alliance for Life. Lawmakers allied with Empower Texans introduce hot-button bills and amendments “just for the purpose of their scorecard, knowing that the people who aren’t just licking their boots all the time are going to vote against them,” says Representative Charlie Geren, a Fort Worth businessman and Republican who has often been a target of Empower Texans because of his support for Straus as Speaker.

Spin is nothing new in politics. Yet Dunn, Sullivan, and Empower Texans carry spin to an extreme, labeling any Republican politician who doesn’t follow Empower Texans’ directions as “liberal” or part of the “Austin establishment” or a RINO—a Republican in name only.

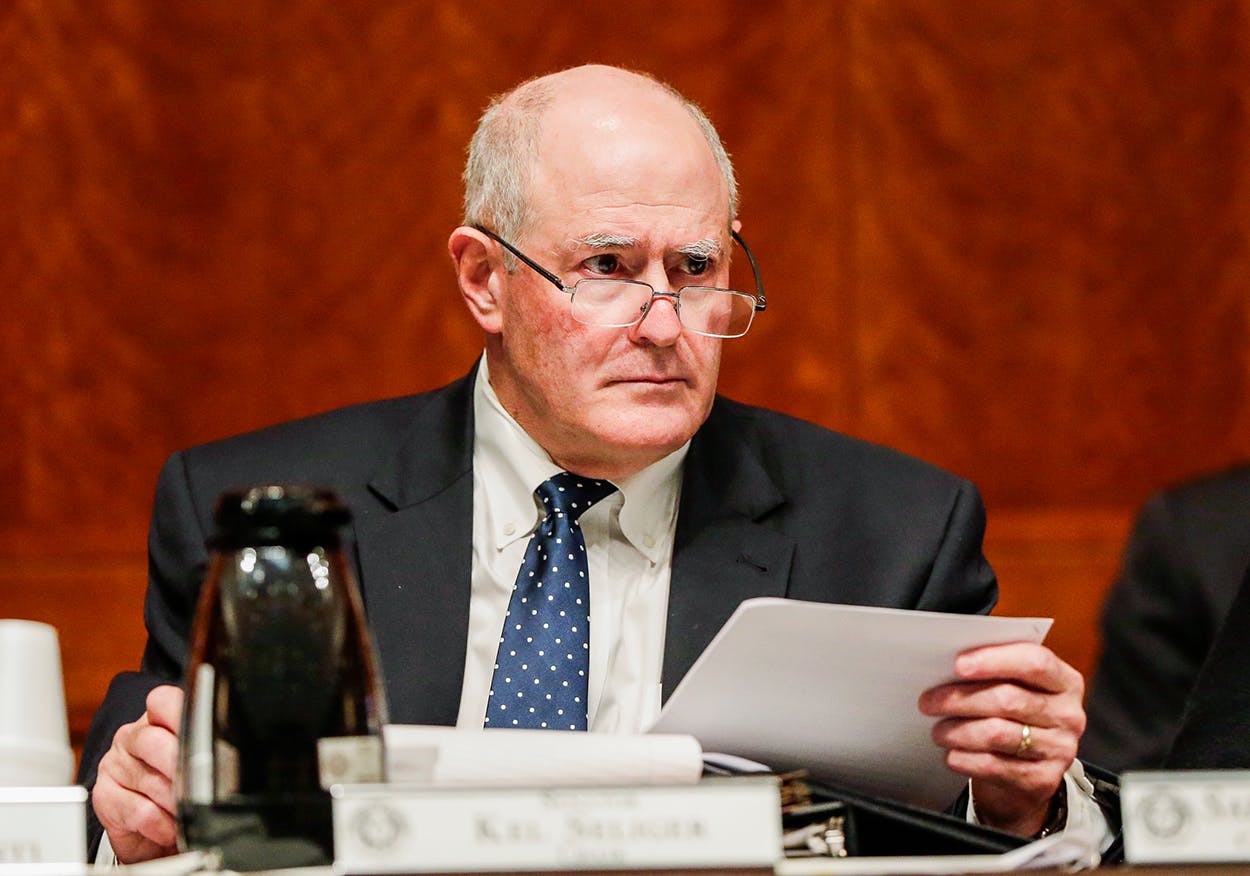

Take, for example, Kel Seliger, a burly man in his mid-sixties who likes to ride Harley-Davidsons. He made his living managing a Panhandle steel company but is better known for his years in politics. In 2004, after serving as the first Jewish mayor of Amarillo, Seliger won a seat in the Texas Senate as a Republican, representing a sprawling West Texas district that stretches from Amarillo to Midland. Around the time he took office, Seliger met Dunn for the first time. “He’s really smart and amiable,” Seliger recalled. “Not particularly garrulous, but amiable.” Dunn asked Seliger about his position on private school vouchers, and Seliger told him that he was a public school supporter.

For the better part of the next decade, there were no signs of political animosity. Seliger established himself as a bit of a maverick in the state Senate, but one with solid conservative credentials. He served on the board of the American Legislative Exchange Council—viewed by the left as a national bill factory for big business—and in 2011, as chair of the Senate Redistricting Committee, he drew the current gerrymandered congressional districts that Democrats and minorities have since challenged in federal court.

But during the years that Seliger was earning his conservative stripes in the Senate, Dunn was pouring money into Empower Texans, which would fashion its own definition of what a conservative was supposed to be. Seliger never had any reason to suspect that Dunn had turned on him until late 2011, when he was blindsided by an Empower Texans attack. The group slammed Seliger for voting for the business tax that Dunn had opposed in 2006 and for favoring an increase in gasoline taxes to pay for highway projects in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, which Sullivan had called “boondoggles.”

Following the attack, Seliger and Geren passed a bill to require nonprofits like Empower Texans to disclose their source of funds whenever they spent more than $1,000 in an election. Governor Rick Perry vetoed the bill. Empower Texans recruited opponents to run against Seliger in his next three elections. And though he won them all, his 2018 primary was particularly tough. Seliger faced two opponents: one a former member of the Texas Public Policy Foundation and the other a former Midland mayor who received $350,000 from the Empower Texans PAC. The double-teaming may have been an attempt to force Seliger into a runoff, where he likely would have been at a disadvantage. It almost worked—Seliger squeaked by with 50.4 percent of the vote, narrowly avoiding a runoff.

The combination of dark money and hardball tactics has had a defining impact on state politics. “Here’s where things become ominous, as Empower Texans and TPPF figure out what political power they can buy,” Seliger said. “Empower Texans has a 501(c)(4) [an IRS-designated nonprofit that can participate in politics], so they don’t have to tell where the money came from. And right now, the majority of the seats in the Republican caucus in the Senate are controlled by Empower Texans and TPPF.”

A physical reminder of that clout is a 42,000-square-foot building on Congress Avenue, two blocks from the Capitol grounds, which TPPF moved into in 2015. (Its 2017 market value was $15.1 million, but because TPPF is a nonprofit, it didn’t have to pay an estimated $336,204 in real estate taxes on its prime downtown property.) “That you’ve got a very few, very wealthy people who essentially own the seats in the Legislature is the very definition of Russian-style oligarchy, and they even have their own Kremlin on Congress,” Seliger said, echoing Breitbart’s characterization of Empower Texans. “And I think that is a bad form of government. I think it’s dangerous.”

House Freedom Caucus chairman Matt Schaefer, a Republican from Tyler, denied to me that the caucus takes its orders from Sullivan or Empower Texans. All sorts of lobby groups keep scorecards of legislators’ votes and put out mailers in their districts filled with distortions, he said. And Schaefer had high praise for Dunn: “The first thing that you’re going to pick up from him is he is deeply involved in his family, a man of faith, and a man who looks at the big picture.”

But there also are Empower Texans apostates. State representative Giovanni “Gio” Capriglione, of Southlake, originally won office in 2012 with the help of Empower Texans, but he separated himself from the group because he got tired of being told how to vote. Empower Texans is “very good about never accurately telling the truth,” Capriglione says. As an example, he pointed to House Bill 550 from the 2017 session. The bill was intended to bring Texas into compliance with federal law by requiring all canoes, kayaks, paddleboards, and other waterborne vessels to have sound-producing devices, such as whistles. Failure to pass the bill would have endangered millions of dollars in federal funds for the state, but Empower Texans decided that voting for it would be a blow to individual freedom and put the vote on its scorecard. The bill died. “Holy crap, this became like the hill to die on for the tea party and for some of the Freedom Caucus members,” Capriglione said.

Empower Texans also sometimes uses assumed names. In this year’s election, the group mailed an attack piece to homes in Geren’s district accusing him of having a “relationship” with a lobbyist—namely, his wife. Pointing out that Geren’s spouse is a lobbyist is fair game. But Empower Texans attacked Geren using one of its alternate names, the Texas Ethics Disclosure Board, and the letter it sent to voters mimicked an official government document, possibly violating a law that prohibits anyone from posing as a government authority. At least one Texas county prosecutor reviewed a complaint against the mailing, though no case has been brought.

Joe Pojman, the executive director of the Texas Alliance for Life, told me that many traditional establishment Republicans whom his group regards as “extremely pro-life” have been labeled as “not Republican” because they haven’t done exactly what is expected of them by the Empower Texans/Texas Right to Life machine. Their scorecards are “disingenuous and dishonest,” Pojman says. “It’s [done] to deceive voters, to deceive Republican primary voters.”

Ahead of the 2012 election Dunn targeted multiple Straus lieutenants in the House, among them Republican representative Vicki Truitt, of Keller, who a few years earlier had briefly thought about running for Speaker herself but ultimately joined Straus’s team and retained her chairmanship of the House Pensions, Investments, and Financial Services Committee.

The first shot was fired in December 2011, by Agenda Wise, a nonprofit that Dunn helped form along with a Wisconsin libertarian named Leslie Graves. Agenda Wise operated under the Empower Texans umbrella and published a newsletter that was sharply critical of Speaker Straus and his allies in the Legislature, and it denounced the conservative pro-business group Texans for Lawsuit Reform for endorsing Truitt, because, according to Agenda Wise, she “had consistently been assailed by conservatives.” But the unhappy conservatives assailing her were none other than officials at Empower Texans, Agenda Wise’s sibling organization.

Truitt then came under the scrutiny of a group called Texas Watchdog. Set up by Dunn’s ally Graves and a libertarian journalist named Trent Seibert as a self-described “independent investigative and enterprise journalism organization,” Watchdog ran a story that was quickly picked up by the Fort Worth Star-Telegram implying that Truitt’s physician-recruiting business had received no-bid contracts from the Tarrant County Hospital District because of her role in the Legislature. Sullivan followed up on the Empower Texans website with a column criticizing the contracts, and Agenda Wise continued the pile-on two weeks later with an article called “Vicki Truitt’s Trouble.”

“These men wish to control the agenda and the votes of members of the Texas Legislature. I refuse to be intimidated by their threats,” representative Vicki Truitt wrote.

Truitt responded with an op-ed in the Star-Telegram, demanding an apology. She noted that her contract with the hospital district was awarded in the early nineties as the result of a bidding process, years before she entered the Legislature. And she claimed that there were financial ties between Texas Watchdog and Sullivan and Dunn. “These men wish to control the agenda and the votes of members of the Texas Legislature. I refuse to be intimidated by their threats,” Truitt wrote, adding, “I am a target because I stand up to these bullies.”

Empower Texans partially financed Truitt’s opponent—future apostate Giovanni Capriglione—spending $33,900 on design and postage for direct mail and $437 for robocalls to the district. In May of 2012, Truitt lost the primary election. Along with fellow Republican lawmaker Jim Keffer, she filed an ethics complaint in 2012 accusing Sullivan of lobbying without registering as a lobbyist and the Empower Texans foundation of acting as a political committee without disclosing its donors. Nearly seven years later, those complaints are still tied up in litigation. Sullivan claims he does not have to register as a lobbyist, because he is a journalist.

During a recent interview, Truitt, who now works as a lobbyist, was hesitant to speak, still fearing the power of Dunn’s organization. I asked her why Dunn and Empower Texans spent so much time and money trying to break Straus’s leadership of the House. She hesitated, took a breath, and then said, “Because they can’t tell him what to do, and I think they really have not liked [having] a Jewish Speaker.”

In Texas, the nonprofits Dunn has set up move money from place to place, making it difficult to keep track of who is paying for what. At the national level, Dunn has ties to a network of libertarian-leaning millionaires whose political spending is similarly secretive.

Two key U.S. Supreme Court decisions made that possible. The first, NAACP v. Alabama (1958), ruled that the constitutional right of free association meant that the NAACP could keep its membership rolls private and therefore refuse to turn them over to the state of Alabama. More recently, Citizens United v. FEC (2010) overturned large portions of federal campaign finance law while giving corporations and nonprofits the right to participate as individuals in elections. While the court specifically upheld laws requiring transparency in political financing, right-wing groups immediately weaponized the decades-old NAACP ruling, arguing that they could withhold the source of their funding on the grounds that transparency would violate their right of free association.

As a result, the amount of dark money—spending by organizations that don’t disclose their donors—in U.S. elections has soared. According to a study by the Center for Responsive Politics, the amount of undisclosed spending jumped from $5.2 million in 2006 to more than $178 million in 2016. “The proliferation of dark money in elections absolutely has the potential of playing a corrupting role in democracy,” says John Dunbar, the chief executive of the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit journalism organization. “Unfortunately, we can’t say for sure, because we don’t know who is giving how much to support whom.”

In Texas, Dunn had already set up a bifurcated system for Empower Texans, with a public PAC and private foundations. Dunn and four wealthy oil families have openly donated 95 percent of the $11.4 million raised by the Empower Texans PAC since 2010. The two Empower Texans foundations, by contrast, have not reported the source of the $13.9 million they raised between 2010 and 2016. Empower Texans, doing business as Texans for Fiscal Responsibility, is a nonprofit that can spend money to affect elections, and Empower Texans is an issues educational foundation.

Nationally, Dunn has affiliated himself with his Agenda Wise cofounder Leslie Graves and her husband, Wisconsin investor and political activist Eric O’Keefe, and Tea Party Patriots cofounder Mark Meckler. (Agenda Wise no longer exists, but Dunn helps Graves direct Ballotpedia, an informational political wiki that sometimes puts an Empower Texans–style spin on the facts.) Graves, O’Keefe, and Meckler are all linked to the conservative network of high-dollar donors tied to libertarian political heavyweights Charles and David Koch. This cross-pollination between Dunn’s operation and out-of-state groups began in earnest in 2010, the same year the tea party took off and Texas Democrats suffered major defeats in the state’s legislative elections.

For example, in 2011 a foundation called Donors Trust contributed $185,000 to the Empower Texans educational foundation and $162,500 to Agenda Wise—more than 90 percent of its operating budget at a time when Graves was the chair, Sullivan the president, and Dunn a board member. Donors Trust, based in Alexandria, Virginia, was set up in 1999 to “safeguard the charitable intent of donors committed to the principles of limited government, personal responsibility, and free enterprise,” according to the trust’s website. Koch family foundations were major donors to the trust. “Donors Trust is basically a front for donors to right-wing causes who want to be anonymous,” Dunbar says.

In 2014, when the Texas Public Policy Foundation was raising money for its new building, twelve donations adding up to more than $554,000 flowed to it from Donors Trust—the kind of donations that Dunn, by then serving as TPPF’s vice chairman, might be more likely to make than the Koch brothers.

The web of finance can get dizzying. During the 2014 Texas elections, one of Dunn’s nonprofit foundations—Empower Texans doing business under the name Texans for Fiscal Responsibility—disclosed spending $1.5 million in dark money to influence state legislative races. And that was on top of the $4.7 million that the Empower Texans PAC spent. If Empower Texans has its way, this sort of thing will become even easier. In a three-year-old lawsuit, the organization has demanded that state courts strip the already-toothless Texas Ethics Commission of any ability to regulate campaign finance.

Dunn’s largesse has not been confined to state races. During this year’s elections, he gave $2.2 million to the Senate Reform Fund, a Super PAC run by Meckler that was solely dedicated to defeating the re-election bid of Democratic U.S. Senator Jon Tester of Montana. Despite the money arrayed against him—and President Trump’s vocal opposition—Tester won by a comfortable three-point margin. The Senate Reform Fund essentially spent $8.98 on every vote against Tester, and lost.

Along with O’Keefe and Houston businessman Leo Linbeck III, Dunn was also part of the Campaign for Primary Accountability, a super PAC that spent about $3 million and targeted fifteen incumbents—eight Republicans and seven Democrats—in congressional primaries around the country. It managed to defeat three Democrats and two Republicans. This spending was not so much ideologically motivated as it was a tactical demonstration project: because congressional districts are gerrymandered to strongly favor one party, the CPA believes that the most effective way to change government is to knock out incumbents in primary elections. CPA wanted to prove that this could be done. (As it happened, one of the Democrats that CPA helped take down was El Paso incumbent Silvestre Reyes—who was defeated by a young and ambitious pol named Beto O’Rourke.)

In an interview, Linbeck praised Dunn for his intellect, his determination to transfer power from Washington to state and local governments, and his desire to make politicians more accountable to citizens. “I never got the sense that he was doing this for personal self-aggrandizement or personal gain,” Linbeck said.

Perhaps Dunn’s most ambitious endeavor is his attempt to rewrite the U.S. Constitution. In 2010 Dunn, Sullivan, and O’Keefe started yet another organization, Citizens for Self Governance. Between 2010 and 2016, CSG raised $21.1 million, including $748,000 from Donors Trust. As part of its agenda, CSG aims to call a convention of the states to revise the Constitution. In its promotional materials, CSG usually claims that the convention would address balancing the federal budget and implementing term limits for members of Congress. But its aims are broader than that. CSG wants to give states the power to overturn federal laws, such as environmental regulations, and Supreme Court decisions on issues like abortion and same-sex marriage. Though pulling off major changes in the Constitution seems like the longest of long shots, the movement reflects the deep animus against the federal government in right-wing circles.

CSG, like Dunn’s other organizations, has an evangelical side. Its website has a section titled “The Bible & Politics,” which links to Wallbuilders, a Christian-right organization dedicated to presenting American history in a religious context. Last year the head of CSG, Mark Meckler, explained in an interview on the Faith Radio Network that Christianity “informs virtually everything we do.”

In almost every respect, Dunn’s two guiding principles—his evangelical faith and his faith in the free market—place him on the right side of the ideological spectrum. But there is one issue on which his beliefs have led him to stake out a position that is not only to the left of much of the conservative movement but to the left of even some members of the Democratic party.

There is one issue on which Dunn’s beliefs have led him to stake out a position that is not only to the left of much of the conservative movement but to the left of even some members of the Democratic Party.

In March 2005, Marc Levin, a young lawyer in private practice in Austin, received a phone call from Brooke Rollins, the president of TPPF. Levin had just completed a Charles Koch Fellowship to write about juvenile justice reform and had published an article in the Washington Times critical of the mass incarceration of drug offenders. Rollins saw the article and invited him to meet with her and Dunn at Austin’s Driskill Hotel to discuss criminal justice policy. As it turned out, Dunn had ideas about criminal justice reform that were much like Levin’s. “Tim was motivated from a biblical restorative-justice perspective,” said Levin, referring to the idea that no one is beyond redemption. “He was also concerned about the growth in the prison population.” (The U.S. has the highest incarceration rate of any country in the world, and the rate in Texas well exceeds the national average.)

Soon after that lunch, Levin joined TPPF to manage Dunn’s Right on Crime program. Their efforts quickly bore fruit. Former state representative Jerry Madden, a Republican from Plano who was chairman of the House Corrections Committee in 2007, says that after three consecutive governors had gone on prison-building binges with no end in sight, then-speaker Tom Craddick sought out alternatives to spending more money for more prisons. Levin and TPPF were well positioned to oblige him, offering reforms that emphasized treating and rehabilitating drug users. To the surprise of many, the reforms passed. The liberal Texas Criminal Justice Coalition was a major player in the fight, but it was the support of the conservative TPPF that helped make passage possible in a Republican-dominated Legislature.

Forging alliances with Republican legislators, liberal reformers, the Christianity-inspired Prison Fellowship, and the ACLU, Levin has, in the years since that first victory, persuaded conservatives around the country to adopt drug courts and alternative treatment programs. As prisons started closing and crime rates dropped in Texas, other states became interested, and former U.S. House speaker Newt Gingrich and several former governors from around the country signed Right on Crime’s statement of principles. “If you lock everyone up, the streets would be completely safe because there would be no one on them. That’s not what we really want, though. What we really want is great communities. I love safe communities,” Dunn told a 2015 conference. “We should be social reformers. We tend to shy away from that notion because we’re conservative. But what we should do is advance.”

Today, the program has offices in six states and has advocated to change laws in more than thirty, Levin said. This past February, Rollins quit her job at TPPF to work in the Trump White House, where she’s pushing criminal justice reform nationally. Although Trump campaigned on a tough-on-crime message in 2016, last week he unveiled a prison reform package that closely follows much of Right on Crime’s recommendations, such as reducing mandatory prison sentences for drug felonies, giving judges the power to ignore sentencing guidelines for nonviolent drug offenders, and funding anti-recidivism programs. Despite opposition from some conservatives, such progressive reforms might, ironically, turn out to be Tim Dunn’s most important legacy.

This year, Dunn and his network were in position to profoundly increase their influence in the Texas Legislature. Although candidates backed by Empower Texans had, since 2010, won slightly less than a third of the time, the group helped defeat five committee chairmen who were allies of Speaker Straus. And a sixth, Jim Keffer, of Eastland, fended off an Empower Texans opponent in 2014 only to see his seat fall under its control when he retired in 2016. Meanwhile, the Empower Texans coalition defeated several mainstream Republicans in the state Senate, giving Lieutenant Governor Patrick a near-absolute command of the upper chamber. If it had picked up some key seats in the House in this year’s primaries, Dunn’s allies in the Legislature would have become a dominant power at the Capitol. But Dunn and Sullivan went too far. A combination of questionable tactics and angst in the business community caused by Patrick’s bathroom bill created a backlash against Empower Texans and Texas Right to Life.

One seemingly unlikely target of those groups was Natalie Lacy Lange, of Brenham. Lange would seem to be the epitome of a modern, small-town Republican woman; she owns a photography business, attends church regularly, and serves as the president of the local school board. Once a teacher herself, Lange believes firmly that public schools are the future of a thriving Texas workforce.

On the Saturday before early voting began in this year’s Republican primaries, politics was far from Lange’s mind. She had spent part of the day playing with her sons—a first-grader and a three-year-old—and their new rescue puppy. That evening, after she’d put her sons to bed and was preparing to watch a movie with her husband, a fellow school board member texted Lange a photograph of a letter that had been sent to voters in Brenham, headed, “Subject: Is school board president Natalie Lange breaking the law?”

The letter, sent by Empower Texans, questioned whether Lange and the Brenham school board had violated state law by approving a “Culture of Voting” resolution urging students and teachers to vote. Empower Texans claimed the resolution was promoted by “liberal activists” who might be illegally using school district tax dollars to get students and teachers to vote against conservative candidates.

Lange had never heard of Empower Texans or Dunn, but being called a liberal in Brenham could be a political kiss of death, even to someone serving in a nonpartisan position. How many of her neighbors now thought she was liberal or perhaps a criminal? She was mortified. At that moment, Lange felt very alone and a little bit frightened. Who would want to destroy her reputation?

She was not alone, though. Similar letters had been sent out assailing school board presidents in Sealy, Nederland, Marshall, and Coppell. The letters came on the heels of an earlier one asking teachers to “blow the whistle” on fellow educators who might spend district money getting people to the polls to vote. Empower Texans’ likely motivation was clear: though the organizations that promoted the voter drive were nonpartisan, the drive was fueled by teachers’ groups that were angry about the Legislature’s failure to pass school finance reform and its attempt to create private school vouchers, for which many blamed Patrick and the Empower Texans crowd.

Educators across the state responded to the mysterious letters by taking to Twitter to castigate Empower Texans and celebrate teachers who’d gone above and beyond for their students. One tweet read, “I just want to #blowthewhistle on all my support staff in my classroom that come in early, stay late and spend their own money helping me make sure our students have everything they need.” Another called out a specific teacher by name, “This amazing teacher pours out her heart everyday into making learning fun!” Some pulled at heartstrings: “@EmpowerTexans I’ve got to #blowthewhistle on a teaching staff that has provided Christmas gifts for a student’s family who was in hard times, helped pay for a student’s medical bills, and buy shoes/clothing for students who needed it.” The tweet-shaming of Empower Texans went on for days.

After the Dallas Morning News published an editorial critical of Dunn and Empower Texans’ tactics, Dunn responded with an op-ed defending the organization. Empower Texans’ spending in the primaries, he wrote, was minuscule compared with the money that lobbyists and the business establishment put into Texas politics. “Most Texans know there is a swamp in Austin as well as in DC,” Dunn wrote. “That’s why the concept of term limits is so popular. But we have term limits in Texas: the primary elections. If all of us outsiders stick together, we can drain the Austin Swamp.”

Educators turned out to vote in those primaries, and mainstream Republican business organizations poured more than $3 million into defeating the socially conservative candidates backed by Dunn’s network. Out of sixteen challenges to House incumbents, Empower Texans knocked off only two and won just three of eight open races. The closest Sullivan came to admitting that his tactics had been a mistake was at a conservative conference this past summer. “We’ve gotten more right than we’ve gotten wrong,” Sullivan said, “but don’t confuse being the least drunk person at the bar with being a model of sobriety.”

The day after the Empower Texans letter arrived, raising questions about whether Lange had broken the law, she met with her minister to pray for strength and then wrote angry responses to Dunn and Empower Texans that she posted on Facebook, where they were widely shared. Attacking volunteer school board members with “slick propaganda meant to stir false discord sinks to a new low,” she wrote, “even for an organization known for ruthlessness and bullying.”

“It’s dangerous to our democracy,” Lange told me when we met in the Brenham School District offices in April. “[Dunn] may be a Christian, but his tactics are not very Christlike.” Lange has a commanding presence and self-assurance. She was still indignant about the attack on her integrity. When I asked her if she had anything to say to Dunn, she replied, “How do you sleep at night?”

Throughout the spring, Dunn turned down my requests for an interview. Since becoming a controversial figure, he rarely talks directly to the news media. But at the 2016 Texas Tribune Festival he rebuffed the idea that he is a man behind the curtain. “If you want to come to Midland and come to the hamburger joint, I’m fairly accessible,” he told the audience. So I decided to fly to Midland and offer to buy him a hamburger. Since he wasn’t returning my calls, the date I picked was a shot in the dark.

I arrived in Midland on a warm, sunny Friday morning and drove straight to the headquarters of CrownQuest Operating. The three-year-old building is shaped like a wide V, the modern panel windows of its exterior framed by brownish limestone set in a Tuscan pattern. The atrium beyond the entrance is airy, with an Old West flair to the decor. A painting by Southwestern landscape artist George Kovach depicts the history of CrownQuest: drilling rigs and oil tanks bear the names of important leases for the company, while a white frame house of worship, labeled CrownQuest Community Church, sits in the background.

I asked the receptionist if she could buzz Dunn for me and was told he was not there and she didn’t know when he would return. So I decided to drive past his house. It sits on almost an acre and a half of land, but in itself it is an unremarkable-looking two-story ranch-style house—a large one, but it doesn’t look like the house of a man likely worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The house appeared unoccupied, so I didn’t stop.

Upon my return to Austin, I found a polite letter waiting for me from CrownQuest’s public affairs manager, saying that Dunn belongs to a number of organizations that serve “Texas citizens and families.” Information about those organizations was available on their websites and elsewhere, the letter continued. “Therefore, Mr. Dunn will decline the request for an interview.” Only later would I learn that my visit to Midland had been ill-timed from the start. Dunn had already left on a trip to Israel, his fifth visit to the Holy Land.

When Dunn returned home, he delivered four talks at Midland Bible Church, more scholarly lectures than sermons, videos of which were posted online. There was no pacing the stage like a TV preacher, but that doesn’t mean he wasn’t animated. During one lecture—aided by music and sound effects—Dunn turned the movie Rocky into a parable of self-struggle and played the role of a center-ring announcer describing sin and death in one corner, with faith and everlasting life in the other.

In the talk he gave three days before the Fourth of July, Dunn spoke of his belief that the laws of man have strayed from the laws of God. The federal government has amassed immense power, he said, and used it to bad ends. The government rather than the Bible has become the arbiter of morality on issues like abortion and same-sex marriage, all the while denying organized prayer in school. Political correctness means “humans decide, not God,” he said. “So now people will decide what’s true. People will decide what’s moral.” Christians were under attack, he said, and the resistance begins in church.

“If the people of God will rise up and walk in the spirit and treat other ones likewise, we will not be defeated.” The Bible, Dunn said, instructs Christians to submit to authority, but in the United States the people are the authority. “So participate in government,” he said, urging members of the congregation to seek elective office. His voice now filled with emotion—some anger, some frustration—Dunn reminded them that challenging the establishment can have a cost. “If you go to the right places, you’ll find that I am the bogeyman that hides under the bed of every lobbyist every night and comes out and jumps up and scares them,” Dunn said. It was an odd note of aggrievement, coming from a man who, in fact, uses secret money and innuendo to defeat his enemies. Perhaps Dunn’s faith blinds him to his own contradictions. Or perhaps his sense of besieged righteousness has convinced him that such tactics are a sad necessity when it comes to saving a fallen world.

As he closed his sermon, Dunn told the congregants that they are on a mission to serve God, to build a political army, preparing Texas and the nation for the kingdom to come.

“There are things you can do and should as you are called,” he said. “The most important thing to do is don’t surrender. God is our king. It doesn’t matter what they tell us. It doesn’t matter what kind of trashing they do to our reputation. If we stand and we are vigilant, we will win.”

This article originally appeared in the December 2018 issue of Texas Monthly. Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Empower Texans

- Tim Dunn