In 2009 Monica Muñoz Martinez drove from Austin, where she was conducting archival research for her PhD in American Studies, to visit her family in Uvalde. Near the end of the trip, she stopped at a Dairy Queen in Sabinal for some sweet tea and found herself gazing at the various objects nailed to the walls. She saw much of the typical DQ paraphernalia: a promotional poster for chocolate-dipped ice cream cones, another for BeltBuster cheeseburgers, and, hanging from the ceiling, a cardboard cutout of a MooLatté.

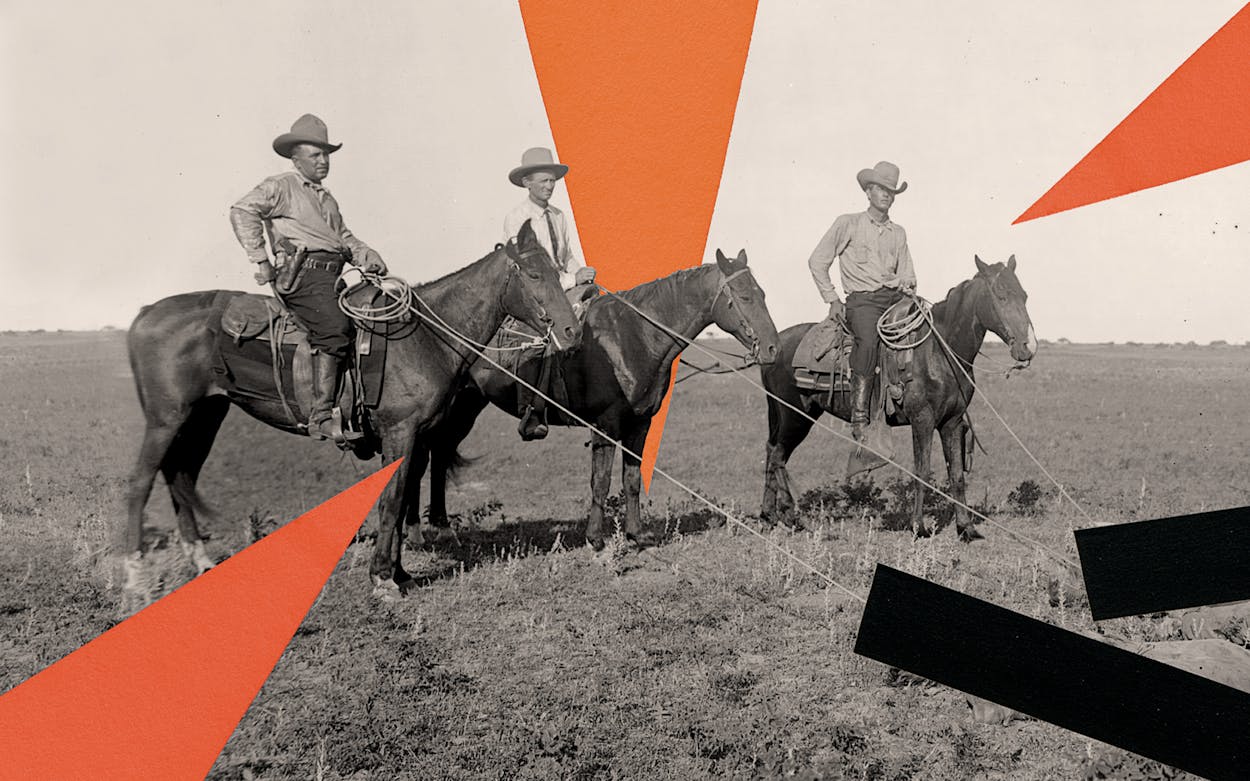

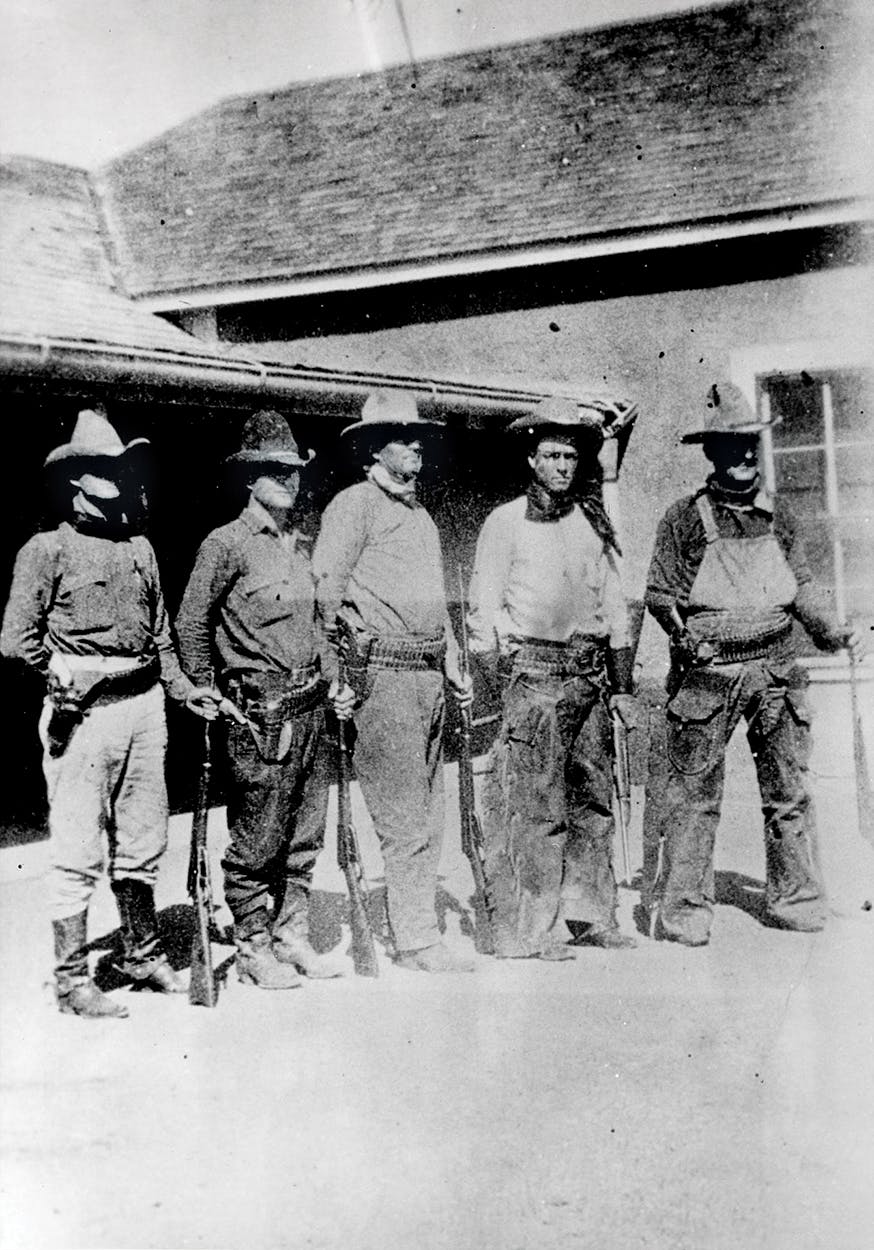

Just next to the MooLatté display, Martinez noticed something unusual. Where one might expect to see pictures of the high school football team there was, instead, a grouping of photographs honoring a different sort of team: Company D of the Texas Rangers, who patrolled the area more than a century ago. When Martinez looked closer, she saw something that stopped her cold: a picture of “a man suspended from the rickety roof [of a wooden shack] by a rope tied around his neck.”

Despite her sense of outrage, Martinez, who was then working on a dissertation about violence against Mexican Americans in Texas, responded calmly: “Dismayed, and trying not to draw attention, I snapped pictures of the installation,” she writes in her new book, The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas (Harvard University Press). “When the counter was empty I talked to two young women working there and asked why [a photograph] of a lynching adorned the walls of a Dairy Queen.” The women, both Hispanic, admitted that they averted their eyes from the macabre photo during their daily work and noted that Martinez was, to their knowledge, the first patron to ask about it. They also told her that the photos had been curated by a local man named Jim Ryan and provided her with his contact information.

Minutes later, Martinez found herself sitting in the living room of Ryan, a retired school superintendent. Among other things, she learned that Ryan was the descendant of a Texas Ranger, a board member of the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, a founder of the historical reenactment group the Badland Texas Rangers, and the producer of a trio of privately funded films celebrating the Rangers. When Martinez asked him about the photo, he genially revealed that it wasn’t a real historical photo. It was a still from a movie.

At first glance, this whole story might sound like a meandering tale about an academic snipe hunt—how a scholar of the memory of violence stumbles upon a memorial to violence at the most unlikely of locations, only to discover it’s a phony. Yet, though this odd anecdote might provoke a nervous chuckle, it also vividly demonstrates one of the central themes running through The Injustice Never Leaves You: the powerful need of so many Texans to celebrate species of violence we would find unacceptable today in any other context.

It’s a dynamic that almost anyone who teaches or writes about Texas’s past grapples with. Many of my students at Texas A&M have firm impressions about Texas history. They see it as the story of how barbed and brutal justice tamed a wild land, bringing civilized modernity to the wilderness and spurring moral and spiritual regeneration. These notions are a part of our identity. We read these enduring narratives in the histories of Walter Prescott Webb and T. R. Fehrenbach. We revisit them in our literature and films. We recite these beliefs about the good and necessary violence in Texas like prayers. All states have bloody pasts. But no state bathes itself in it quite like Texas.

Martinez is unwilling to let this stand. Now an assistant professor of American Studies at Brown University, she has crafted an unflinching book that refuses to repeat the same old justifications for violence. Instead, she demonstrates how violence often makes problems worse and poisons communities for decades afterward—it turns out that people hold fiercely to the memory of a loved one’s murder.

The Injustice Never Leaves You focuses on the 1910s, which, due partly to spillover from the Mexican Revolution, was one of the bloodiest periods in Texas history, leaving hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Mexicans dead along the border. But Martinez doesn’t settle for describing the incidents of madness and violence themselves. Her main concern is with the sharp divisions wrought, even today, by the pain of old injustices.

Much of the book is structured episodically, with a chapter apiece devoted to three terrible crimes: the 1910 lynching of twenty-year-old Mexican immigrant Antonio Rodríguez in Rocksprings; the 1915 murder of Tejano landowners, businessmen, and public officials Jesus Bazán and Antonio Longoria by Texas Rangers in Hidalgo County; and the 1918 Ranger massacre of fifteen Tejanos between the ages of 16 and 64 in the small West Texas community of Porvenir. Later chapters take a broader perspective, portraying the state’s fixation with violence and its symbols (public celebrations, reenactments, photographs of lynchings) as a kind of idolatry and examining the roles of amateur and professional historians in constructing our collective sense of Texas’s past.

Though The Injustice Never Leaves You is a page-turner, it’s not easy reading. Nor should it be. It is a haunting book. Martinez’s careful dissection of the murder of Rodríguez exemplifies her unsparing approach. She depicts the crime that started the chain of events—the murder of an Anglo woman—and the mob mentality that quickly cast the blame on Rodríguez, a laborer who happened to be nearby. The reader learns details of the lynching (a mob kidnapped Rodríguez, tied him to a mesquite tree, and burned him alive) and old theories about the woman’s murder (some believe her husband did it), but Martinez focuses more intently on the episode’s aftermath. For more than a century, the Hispanic residents of Rocksprings have refused to forget the tragedy. Even to this day, they see the lynching as a curse that continues to poison relations between local Anglos and Hispanics. “It’s always been like this in this town. It’s not going to change,” local resident Vincent Vega told Martinez of the legacy of Rodríguez’s murder. “We’ll speak to each other, but that’s about it. That’s how things are. There’s just too much hate.”

Martinez’s focus turns from Tejano victimization to Tejano agency in the book’s fourth chapter, which chronicles state representative José T. Canales’s 1919 efforts to bring criminal charges against several Texas Rangers for their years-long campaign of indiscriminate killing of Mexican Americans. Martinez documents the grinding racism Canales endured during state legislative hearings as well as the threats of physical violence that famed Texas Ranger Frank Hamer made against him.

The House-Senate committee that was formed to investigate Canales’s charges acted like a modern-day truth and reconciliation commission, generating a tremendous amount of revelatory testimony. The committee chose not to recommend criminal charges against any Rangers (which angered Canales), yet soon after the hearings, several Rangers were pushed out, the force was reduced in size, and the crazed level of bloodshed diminished. Even so, few remember the investigation today.

An Atlas of Terror

In addition to writing and teaching, Martinez heads up mappingviolence.com, a website that features interactive maps that portray episodes of racial and ethnic violence in Texas.

Perhaps that’s about to change. On the heels of the publication of Martinez’s book, the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, in Austin, will hold a conference marking the committee’s centenary next year. (Of late, the Bullock has been groundbreaking on the subject of anti-Mexican violence. Its 2016 exhibit “Life and Death on the Border, 1910–1920” movingly documented the bloody decade that is the focus of Martinez’s work.)

Many Texans will dismiss The Injustice Never Leaves You out of hand. There are defensive souls who cannot bear any criticism of the myth of the Texas Rangers or countenance the idea that the historical violence many extol today has lingering consequences. In these politically charged times, some will assume the book simply has it out for Anglos. But Martinez refuses to engage in that sort of racial reductionism; she forthrightly acknowledges that many Anglos at the time recognized these crimes for what they were. Several Anglo witnesses to the massacre of fifteen men and children in Porvenir, for example, refused to stay quiet. Robert Keil was a young U.S. Army cavalryman stationed nearby who was tasked with helping the Texas Rangers round up the men of Porvenir for questioning about an incident in which a bank was robbed and three Anglos were killed. The Rangers then sent Keil and his fellow soldiers miles away. After the soldiers heard gunshots in the distance, their commander ordered them to return, where they discovered lifeless, mangled bodies and screaming women and children. Keil later wrote a memoir, published posthumously thanks to the efforts of his daughter, who recalled how the murder of people he regarded as friends tormented him for the rest of his life. We never stop paying the price for injustice.

Institutional cruelty is still a part of our lives. The federal government’s recent practice of separating the children of Central American refugees from their parents is proof that, for all too many, people of Hispanic descent are somehow less than human. After the headlines from this particular story fade, as they inevitably will, many people, victims and perpetrators alike, will never forget what happened. Their lives will be stained in ways that would be familiar to many of the people portrayed in The Injustice Never Leaves You. Martinez has written a book that bravely and convincingly urges us to think differently about Texas’s past. But she has also written a book that tells us something about the future we are creating right now.

Carlos Kevin Blanton is a professor of history at Texas A&M–College Station and the author, most recently, of George I. Sánchez: The Long Fight for Mexican American Integration.