I first visited Austin during the summer of 1975, when I was nineteen. Thirteen years earlier, the novelist Billy Lee Brammer had described the city as possessing “room enough to caper.” I remember capering plenty that week and not sleeping much. I left town and returned to Oklahoma with lingering post-amphetamine anxiety and a reminder scribbled to myself on a notepad from the old Ramada Inn near the Capitol: “Read Shrake’s Blessed McGill.” I have no idea who recommended the novel to me.

Whatever misbehavior I committed that week had to pale in comparison to the high jinks Edwin “Bud” Shrake was up to at that time. During the seventies he was an exemplar of Austin excess, with a seemingly endless capacity for whiskey, cocaine, weed, acid, and all-around debauchery. Shrake presented a larger-than-life figure in those halcyon days of old weird Austin. Benders initiated by Shrake and friends like Jerry Jeff Walker could last for the better part of a week and were the stuff of legend. Gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson once showed up to partake in the revelry but collapsed after a mere forty hours. Shrake and company carried on without him for another couple of days.

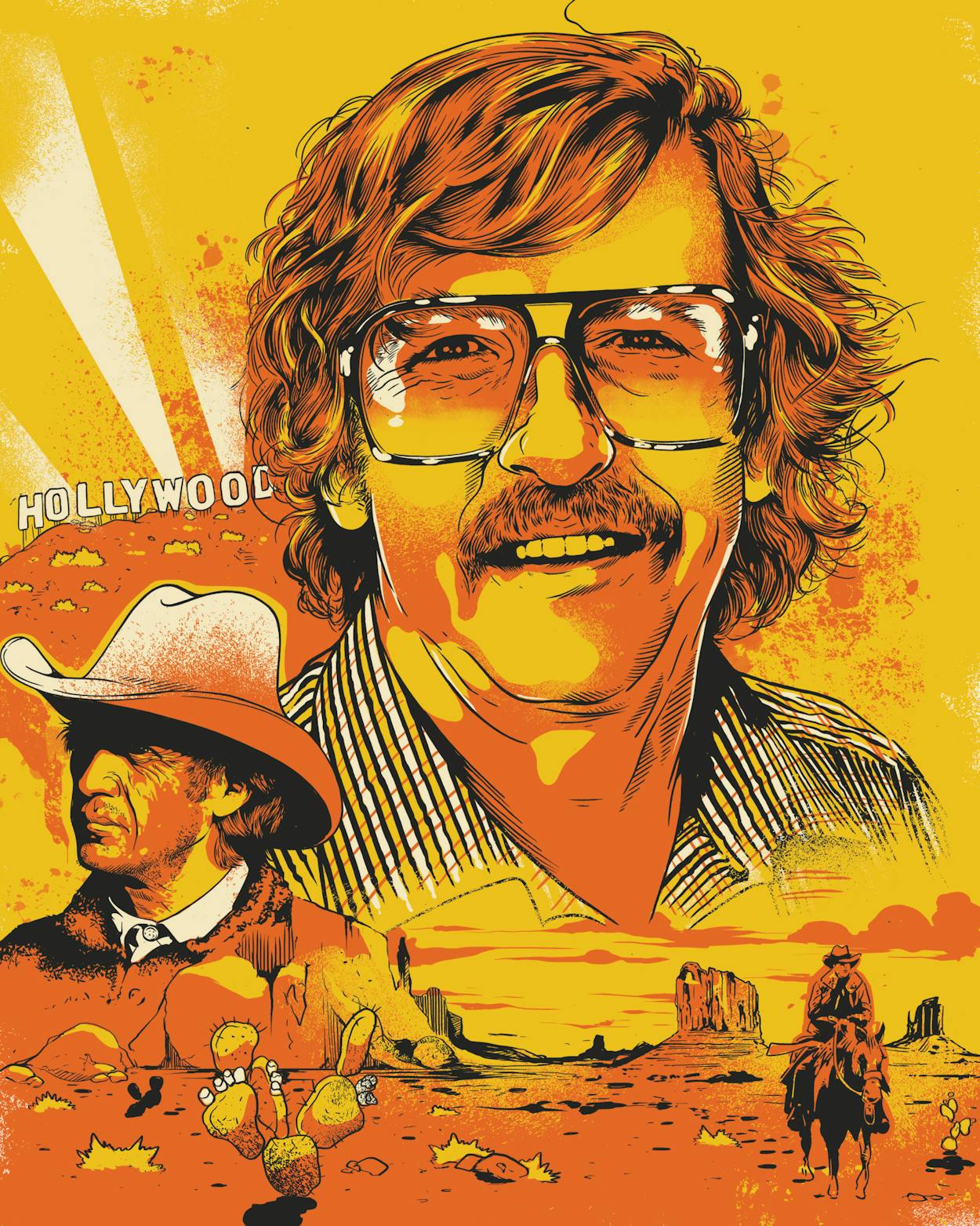

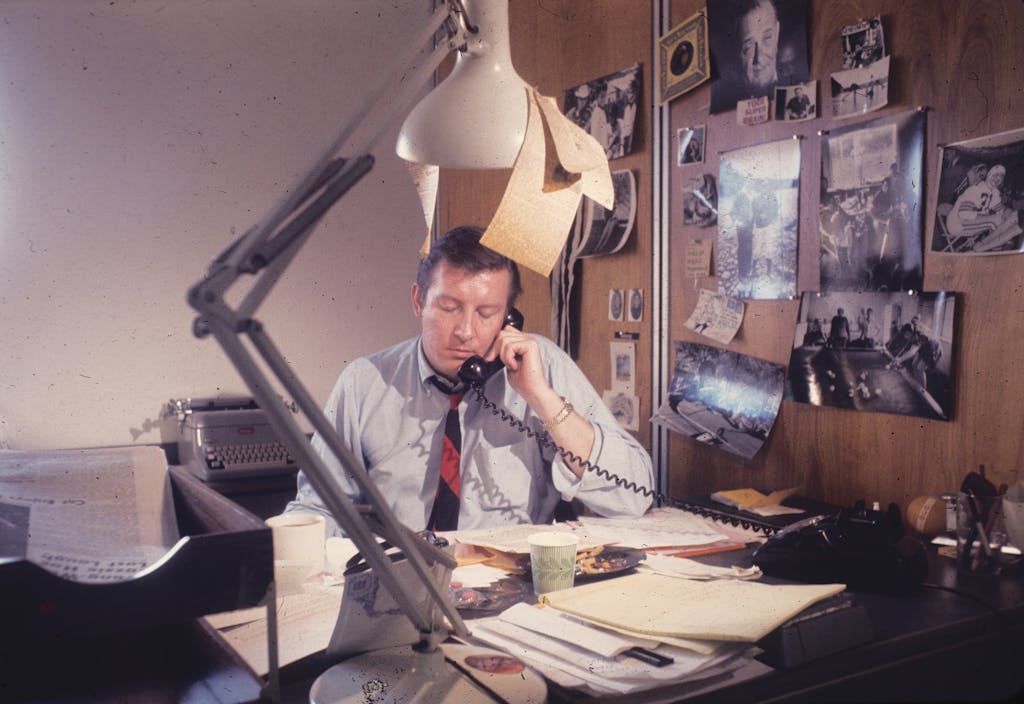

But the Fort Worth native also managed to write like a man possessed. He published five novels between 1962 and 1973, two of which, Blessed McGill and Strange Peaches, turn up on many lists of Texas classics. Blessed McGill, which appeared in 1968, is a revisionist western that shredded the typical cowboy clichés, especially in its unhackneyed presentation of Indigenous and Hispanic characters. Strange Peaches (1972) is a contemporary western whose narrator, a TV actor, becomes a drug-smuggling outlaw after experiencing the atmosphere of hate in Dallas at the time of the Kennedy assassination. Shrake churned out this string of books while living in Austin, Dallas, and New York City and holding down high-profile jobs as a sports columnist for the Dallas Morning News and then as an associate editor at Sports Illustrated.

He also began selling screenplays to Hollywood, two of which, J. W. Coop and Kid Blue, defied the glacial pace of most movie development and hit theaters relatively soon after they were written. Members of his Texas social set were perplexed by how he accomplished it all. Pharmaceuticals provided at least part of the answer: “If I needed a boost, I had some orange heart-shaped pills in a prescription bottle in my shaving kit,” Shrake’s alter ego, Richard Swift, says in Shrake’s final novel, Hollywood Mad Dogs (Texas A&M University Press, October 6), which is being published eleven years after his death.

Hollywood Mad Dogs is a roman à clef drawn from one of the most frenetic periods of Shrake’s life, the tail end of the seventies. Shrake, who left Sports Illustrated in 1978, signed a lucrative contract with a New York publisher to produce an epic-length novel set in the Republic of Texas that would climax with the battle at Plum Creek, in Central Texas, between white settlers and Comanche. Shrake collected an advance but had trouble making progress on the book. Movie work and his social life kept getting in the way. Shrake decided he had to flee Austin to get his novel written.

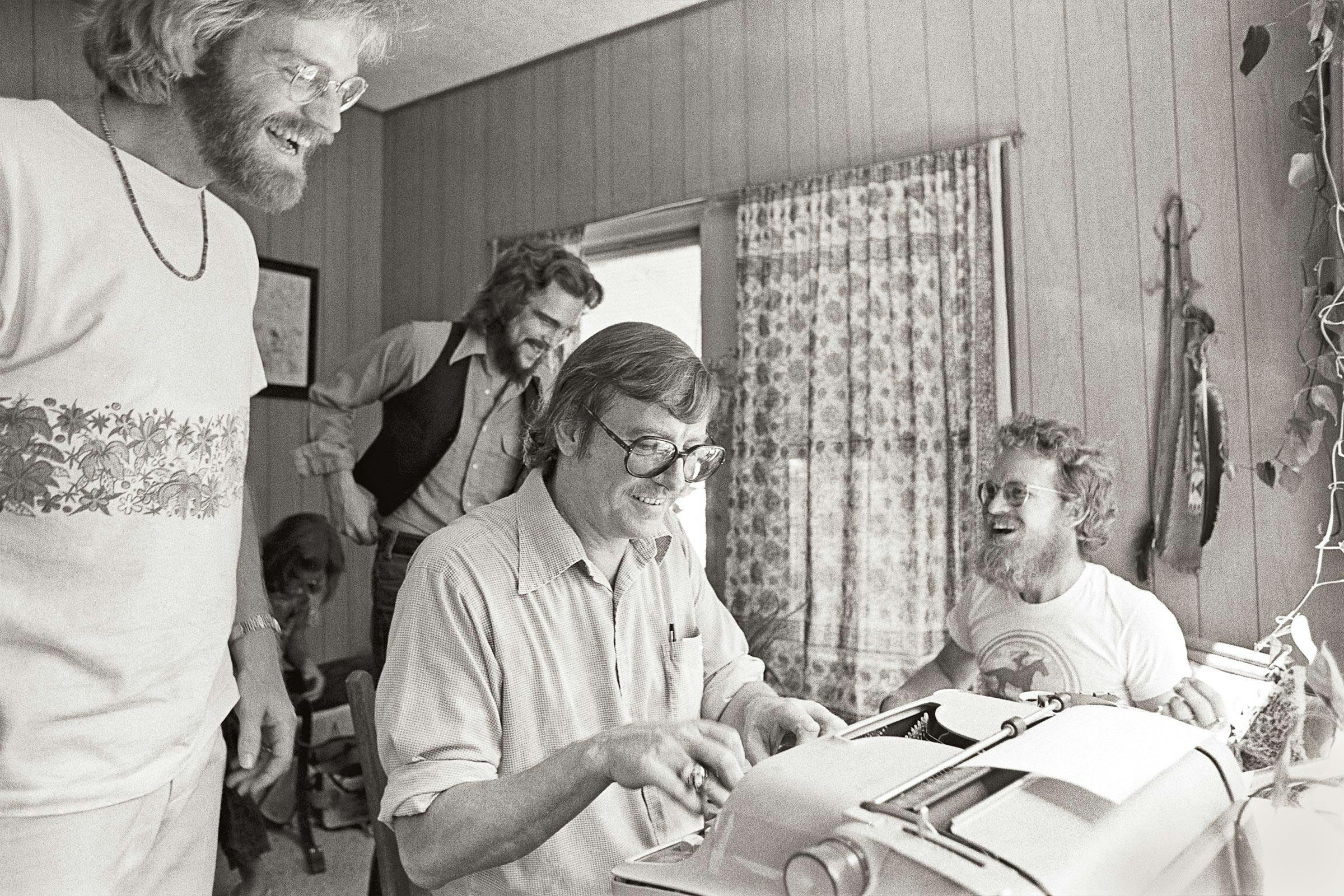

His friends Eddie Wilson (founder of the Armadillo World Headquarters music venue) and Fletcher Boone and Jim “Lopez” Smitham (proprietors of the popular Austin restaurant Another Raw Deal) came up with a solution. They located an apartment for Shrake in San Antonio’s castle-like Clifford Building, on the River Walk. A cigar-smoking, gin-swigging woman named Geraldine Gatewood managed it and made sure nothing got out of hand. She locked the doors promptly at eleven every night, ensuring limits on revelry.

Shrake agreed with his pals that the Clifford would be a good place to get some work done. He enlisted another buddy, former Dallas Cowboys wide receiver Peter Gent, then riding high on the success of his novel North Dallas Forty, to help with the move. But before he could even get settled into his new perch, Shrake received a phone call on the unlisted number he’d just had installed.

Shrake was shocked to hear Hollywood agent Jim Wiatt—whom he didn’t know; he never figured out how Wiatt got his new number—telling him that Steve McQueen, star of such hit movies as Bullitt and The Getaway, wanted to meet him for breakfast the next day. McQueen had just read Blessed McGill and decided that Shrake could save the script of a revisionist western called Tom Horn that McQueen was slated to star in. The novelist Thomas McGuane had been hired to write the screenplay, but after hammering away at it for months, he delivered a 220-page draft that would have made for a three-and-a-half-hour-long movie. That was unworkable. Could Shrake catch the next plane to L.A. and whip the script into shape, McQueen wanted to know? Shrake said yes. Nearly twenty years would pass before he returned to his Comanche saga.

Tom Horn was to be a biopic of a real-life Army scout during the Apache Wars who worked as a cattle range detective, a ranch hand, a Pinkerton agent, and a hired gunman and was also something of a mystic. He became well-known throughout the West and was eventually hanged for murder in 1903, though his guilt has remained a subject of controversy.

Horn’s story obsessed McQueen, who was at a crucial juncture in his career. After walking away from the movies for a couple of years following his blockbusters Papillon and The Towering Inferno, he starred in a pet project, a film adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s nineteenth-century drama An Enemy of the People. It was a box office dud, even by art house standards. McQueen desperately needed Tom Horn to be a hit to get his career back on track.

Shrake left San Antonio, set up shop in L.A. for a few months, and went to work, pill bottles in hand. Shrake quickly delivered what McQueen requested, though McQueen ultimately cobbled together scenes from both Shrake’s and McGuane’s efforts. That, combined with the effects of substantial budget cuts, made the film seem more like a series of disconnected scenes than an integrated whole. It was poorly received by critics and the public, dashing McQueen’s hopes.

For more than a decade, he had been one of Hollywood’s most bankable stars, nicknamed the King of Cool. Now, with two consecutive bombs under his belt, he had feeble claim to that throne. Not that it could have mattered much to him by then; just months after Tom Horn hit theaters, McQueen died of a rare form of lung cancer. Even during filming, Shrake and others had observed the star struggle with coughing episodes and exhaustion.

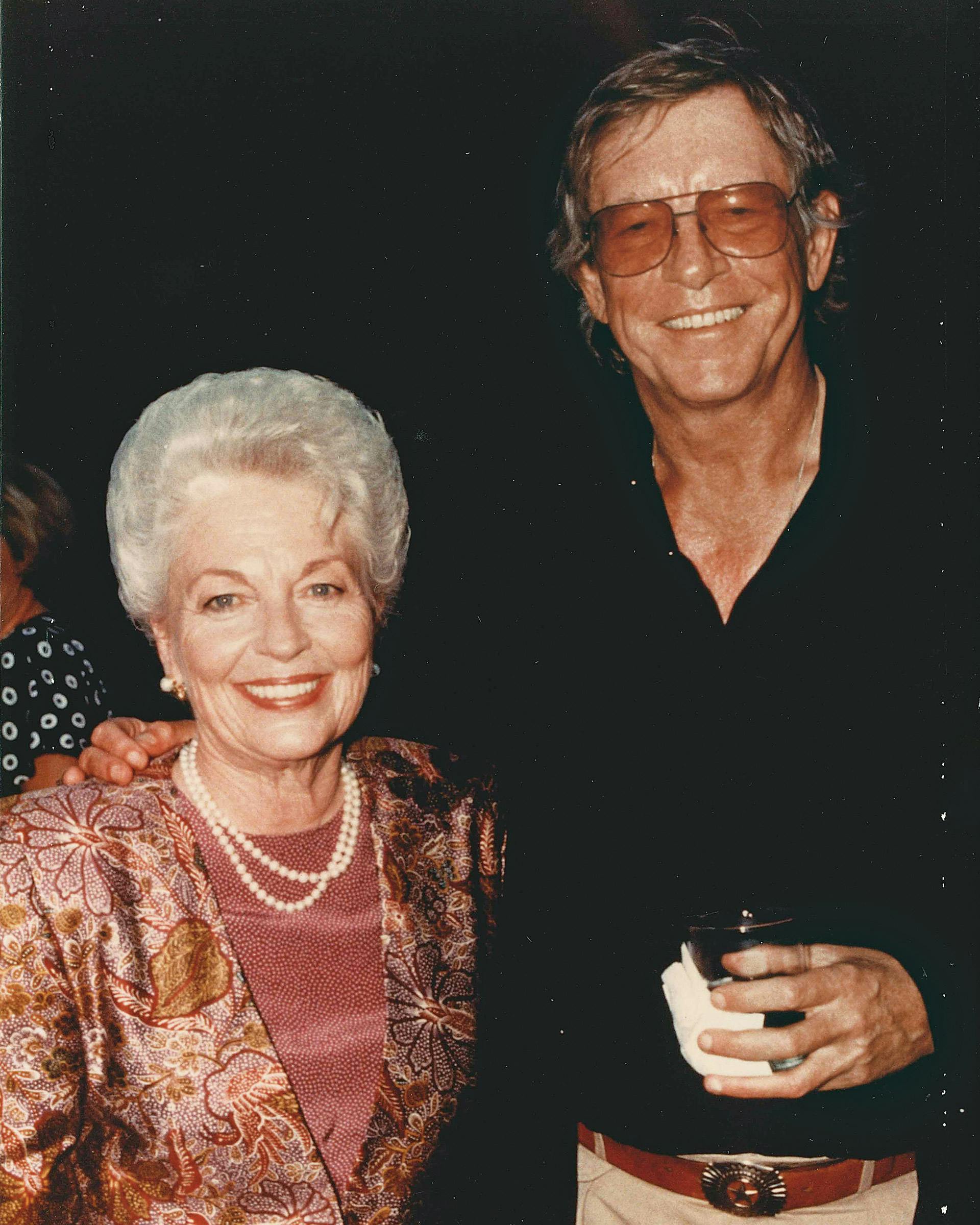

Shrake returned to Texas and stored his Tom Horn experiences in the back of his mind for a quarter of a century. His life took off in unexpected ways during that time. In the mid-eighties he embraced sobriety—save for a daily joint to smooth the rough edges off the world. Shrake and his longtime friend Ann Richards, also a recovering alcoholic, began a romantic relationship that lasted until her death, in 2006. Though they never married, he acted as her consort during her term as governor in the early nineties.

After the Tom Horn experience, Shrake published four more novels, including, in 2000, The Borderland, the two-decades-late Comanche tale he had abandoned in 1978 when Hollywood came calling. He also penned as-told-to autobiographies of his old friend Willie Nelson and the former Dallas Cowboys coach Barry Switzer. He was the architect of Harvey Penick’s Little Red Book, a best-selling compendium of golf philosophy that made both Penick and Shrake wealthy men.

In the early 2000s, Shrake reread his 1972 novel Strange Peaches for the first time since its publication. He was happy to realize how well the book’s alcohol- and drug-laced tour of 1960s Dallas held up. Its nihilistic tone and dark humor released his pent-up Tom Horn memories and provided a road map for how to turn them into fiction. He finished Hollywood Mad Dogs in the spring of 2008, but his agent wasn’t terribly enthusiastic about the book, and the few publishers she sent it to either weren’t interested or wanted to sanitize it in ways that Shrake was unwilling to accept.

In late August 2008, Steven L. Davis, the curator of the literary archives at the Wittliff Collections, in San Marcos, stopped by Shrake’s home in West Lake Hills to pick up archival material that Shrake was donating to the Wittliff. As Davis was heading out, Shrake walked to his car with a manila envelope and said, “Here—add this to the archives.” It was the Hollywood Mad Dogs manuscript. That night, Davis read it in one sitting. He thought it was one of Shrake’s best books.

Not long after, Shrake learned that he had terminal lung cancer and had less than a year to live. As he was getting his affairs in order, he asked his sons to sit on the novel for a few years and then submit it to publishers. A decade later, Texas A&M University Press decided to give the book a chance, as part of its Wittliff Collections Literary Series.

Judging from Hollywood Mad Dogs, the Tom Horn project was no fun for Shrake. He witnessed Hollywood shifting from its “second golden age”—bookended roughly by the release of Bonnie and Clyde, in 1967, and Star Wars, ten years later—to a blockbuster mentality that had no place for the sort of cowboy character study McQueen had in mind.

Hollywood Mad Dogs opens with Shrake’s doppelgänger, Richard Swift, being introduced to Adam Wachinski, a producer of low-minded fare who is in the company of a naked fourteen-year-old starlet. Wachinski wants Swift to write a screenplay for him. Swift declines because he’s already committed to the Tom Horn–like project spearheaded by Jack Roach, a character who shares many of Steve McQueen’s traits.

Roach—as that unsubtle surname suggests—turns out to be little better than the über-crass Wachinski. Soon after Roach and Swift start working together, the actor invites the writer into the “Truth Room” of his house, a place where Roach and his guests pledge to be totally honest with each other. Roach, who knows he’s dying of cancer, promptly lies to Swift about his health. Later in the novel, Roach begins sleeping with a Texas-born movie star whom Swift has been romancing. He is, in short, a narcissistic, sociopathic manipulator who is capable of betrayal at all levels. It’s unclear if this reflects Shrake’s view of McQueen or is an exaggerated portrayal of him.

Though most of the characters Swift meets as he navigates Hollywood are similarly monstrous, one thing that distinguishes the book from many of the anti-Hollywood novels that have preceded it—a lineage that stretches from The Day of the Locust through What Makes Sammy Run? and The Player—is Shrake’s sympathy for the denizens of the town’s lower rungs. Hollywood Mad Dogs is filled with such characters as a nightclub singer, a parking valet, and even a philosophical coke dealer. Shrake had, without much effort, moved into a fairly rarefied circle of Hollywood success, but he always felt like an outsider there and identified with those on the industry’s margins.

Other than such moments of kinship, Hollywood Mad Dogs embraces the deep cynicism that’s almost obligatory in Tinseltown novels. No one inside the industry has a secret heart of gold. Good movies occur by serendipity, not artistry. Betrayal is the norm, not the exception. All of these notions ring even truer today in the wake of Harvey Weinstein’s recent conviction and other #MeToo scandals.

Shrake keeps all of this fresh with his unerring rendering of morally ambiguous characters and the brutal sense of humor that had enlivened his prose since his days as a sportswriter. At one point, Sean Connery (Shrake sprinkles real, bold-faced names among his fictional characters) is enraged because he thinks Roach’s foursome is crowding him on a golf course and threatens Roach with a putter brandished like a sword. “I respect the etiquette of golf,” Roach tells him. “I wouldn’t hit into your fat, lazy ass, but for God’s sake, man, speed it up.”

It’s baffling that no one in the New York publishing world snapped up Hollywood Mad Dogs while Shrake was still alive. That it took a dozen years for us to get the chance to read it is something of a disgrace. But, happily, this book’s fate had a Hollywood ending. It was worth the wait.

Austin writer W. K. Stratton’s most recent book is The Wild Bunch: Sam Peckinpah, a Revolution in Hollywood, and the Making of a Legendary Film.

This article originally appeared in the October 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Lights, Camera, Agony!” Subscribe today.