The state’s oldest licensed radio station, which turns one hundred next year, is about as close as a municipal entity can get to being a tall tale.

WRR-FM is publicly owned, but it’s not publicly funded, nor is it public radio. Its studio sits on the grounds of the State Fair of Texas, in the shadow of the Ferris wheel. It’s been a training ground for internationally renowned radio voices, but at times it’s also been so unpopular that disc jockeys could broadcast dead air. The station’s ownership—the city of Dallas— hasn’t changed for a century.

This fall, the station is hosting a history exhibit in advance of its upcoming centennial (the exhibit is on view at Dallas’s NorthPark Center until September 16, and will then head to the Hall of State at Fair Park and eventually city hall, though dates haven’t yet been announced). As photos, archives, and other memorabilia show, licensed Texas radio began as a humble emergency dispatch in a fire station.

WRR’s story began when a fire consumed the telephone lines that Dallas dispatchers used to call police and fire precincts. The man tasked with finding a solution was an electrical engineer, organist, and technology geek named Henry “Dad” Garrett, who’d been Texas’s first car dealer (for National Electric in 1901), installed the State Fair’s first electric lights, and would go on to build the city’s first traffic signals, patent a water-powered car, and create his own early version of a radio alarm clock.

“A Jules Verne of Dallas, is what I would call him,” says John Slate, Dallas’s city archivist.

Assembling spare parts from garage radio enthusiasts, Garrett constructed a radio dispatch in the city’s central fire station. In 1921, WRR became the first licensed radio station in Texas and the second in the United States, airing emergency calls to police and fire vehicles.

In theory, you could have sat in your living room, listening to the soothing sounds of urgent crises on your radio. In practice, however, you didn’t have a radio unless you made it yourself. The golden age of radio, which by 1947 would turn 82 percent of Americans into broadcast listeners, wouldn’t really take off until the 1930s; WRR was a decade ahead of its time.

“There were only amateur radio stations up at the time,” Slate explains. “There were also no commercially produced receivers, so people were making radios out of anything you can find. There are accounts in the Dallas Morning News of people using things like old box springs, mattress springs, as antennas.”

There was ample free time between dispatch calls, so Dallas’s firefighters started to air their own banter. Garrett spun his classical records and even lugged a piano to the station so his teenage daughter, Letitia, could give a live concert.

“The dispatchers were almost like the original disc jockeys,” says Amy Bishop, host of WRR’s midday show. “During the time when they didn’t have emergency communication, someone said, ‘Why don’t we start playing music?’ People started coming on telling jokes. Some enterprising person thought ‘Hey, we’re starting to reach more people, what if we could sell this time?’”

When the operation outgrew the fire station—and the antenna on top of city hall—it moved through a series of local hotels before landing permanently in Fair Park. In 1931, after a decade of format-sharing, the emergency dispatchers left for a less public frequency.

After World War II, WRR launched an FM station that stuck primarily to classical music, becoming all-classical in the 1960s. The AM side, meanwhile, slid into a no-format anything-goes carnival of pop, blues, comedy, variety shows Bishop calls “almost vaudeville,” news, live sports broadcasts (including the brand-new Cowboys, SMU basketball, and the now-gone Dallas Texans, Chaparrals, and Black Hawks), and some of Texas’s first traffic reports, aided by informants who literally sat on the roofs of tall buildings and called in what they saw.

WRR launched the careers of dozens of talented hosts—but, on a bureaucratic budget, it couldn’t afford to keep them. “We have a lot of correspondence going on back and forth saying we’ve got to pay people more money because we keep spending money training them and then they go on to other places,” says Kristi Nedderman, Dallas’s assistant archivist.

Those talents included John Peel, who was a DJ at the BBC for more than three decades; Jim Lowe Jr., who boldly programmed hours of Black blues musicians like John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters in the early fifties (his teenage listeners included Jimmie and Stevie Ray Vaughan); and Frank Glieber, who later called play-by-play for the Texas Rangers and whose wide frame acquired the station nickname “Round Mound of Sound.”

In December 1970, WRR hired Brad Sham, then 21 and now the longtime radio voice of the Dallas Cowboys. It was his first job in radio, and it paid $600 a month.

“It’s the quirkiest and in some ways most interesting place I’ve ever worked,” Sham says. “What I didn’t know was how unusual a place it was. It was a great place for me because I probably got opportunities to do things faster than I would have almost anywhere else.”

Sham joined the AM band’s news team, an island of sanity in an environment he recalls as an “eclectic assemblage of pros, semipros, has-beens, and hangers-on.” He worked a noon news broadcast, to which, after breaking down his bosses’ resistance, he added a five-minute sports report.

“They said, ‘Okay, but we’re not going to pay you any more,’” Sham recalls. “I wound up doing the first sports call-in radio show in Dallas–Fort Worth the same way. I kept pushing. I kept nudging and making myself a nuisance until they said, ‘Okay, we’re giving you an hour at six on Sunday night, but we’re not paying you any more.’” His persistence led to a fifty-year career in radio.

George Gimarc, a longtime punk and alternative DJ and creator of the reference Punk Diary, spent four months at the station in 1975 as a high school senior, working a news internship with hours so early he could still go to school afterward. He recalls driving onto the fairgrounds each morning at 2:30 a.m. in a 1940 Ford sedan, past police cars cruising with their lights turned off. On his very first day, he was plunged into one of the biggest news stories of the year.

“About 4:45 a.m. everything in the newsroom went crazy,” Gimarc remembers. “The news teletype went crazy. It was the fall of Saigon: evacuate everyone, helicopters on the roof. So I had to write up copy on all of that and get it to the newsroom, and then I had to get on the phone, as a teenager, and tell all the newsmen to come to the station because we had an emergency situation. Nobody knew who the hell I was … ‘I’m George, I’m the new guy, you gotta come in because Saigon is falling.’ I met everyone in the station that way.”

By the time Gimarc and his ancient car arrived, WRR-AM was experimenting with an all-talk format in an attempt to halt a years-long ratings slide. Sham’s sports call-in show briefly grew to five nights a week. John Henry Faulk, an Austin-born folklorist who’d been blacklisted by McCarthy-era Hollywood and who had won a defamation suit against his accusers, came to WRR to host a show he thought would make his comeback. But talk didn’t work: Dallas cut its losses and sold off the AM station in 1978.

The city still owns the FM station, which is likely the only commercial station left in the United States owned by a government body. It’s still all classical.

Well, almost. In 1978, Dallas added a new obligation to its broadcaster: airing city council meetings. The meetings are streamed and saved online, and they’re ratings suicide—a 2018 study reported that listenership drops 82 percent during council business—but WRR still begrudgingly airs them. Pro-broadcast council members cite unreliable internet and cell connections in the city’s poorest areas.

But being city-run has advantages, too: The station, which has nine paid staff members, can stay classical all day without corporate pressure to choose a trendier format or become an affiliate of NPR. Taxpayers don’t cover a cent of WRR’s $1.9 million annual budget—as Bishop puts it, “We have to kill what we eat”—but the city is a safety net, as is a Friends of WRR charity that occasionally steps up to purchase equipment or dissuade politicians who might want to sell.

Outside of council meetings, WRR’s listenership is healthy for a classical station. Demographic reports show that more than a third of listeners are younger than 35—an impressive statistic in a genre whose fans are often gray-haired. Until the coronavirus shredded arts budgets, advertising was robust.

And even the dullest council meeting couldn’t compare with the moment, back in the AM station’s seventies dark ages, when literally nobody was listening. Hal King, who later appeared on WFAA, was on the air, and Brad Sham was with him.

“I was in the studio one day waiting for a news assignment, and Hal’s on the air and we’re talking,” Sham narrates. “And Hal sits back at the control board and he said, ‘I’ll betcha if we had dead air nobody would notice.’ I say, ‘No, no way.’ I’m a kid, I’m so impressionable. These guys are bigger than life to me. He’s got a record playing. He then takes another set of turntables … and he gets out a sound effects record. Cues it up to the sound of an explosion. I saw this with my own eyes. The record ends and Hal turns on the mic and puts his finger on the play button on that cue turntable, into the mic he says, ‘That was Les Brown and His Band of Renown, it’s one-fifteen on WRR, fifty-seven degrees,’ and in the middle of the sentence, as natural as you please, he pushed the button and played the sound effect of an explosion and put his feet up and said, ‘Let’s see how long it takes for someone to notice.’ It was fifteen minutes. The phone rang and he said ‘WRR’ and someone said, ‘Do y’all know you aren’t broadcasting?’

“I don’t know yet if management ever knew what happened.”

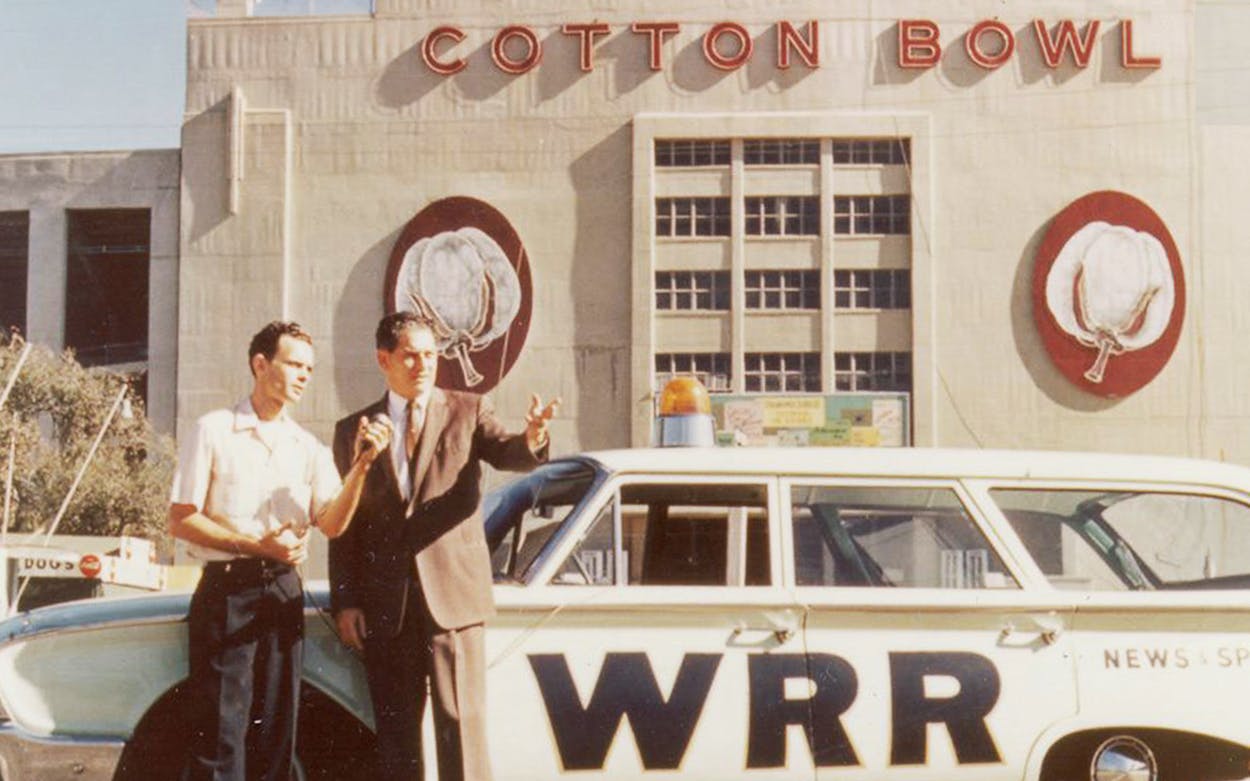

Correction: This story has been updated with edits to two photo captions. The WRR station wagon is shown outside the Cotton Bowl, not the Centennial Building. And the WRR facade pictured in the 1930s is at Fair Park.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Music

- Dallas