Heads up, Texans. The crested caracaras are coming for your roadkill.

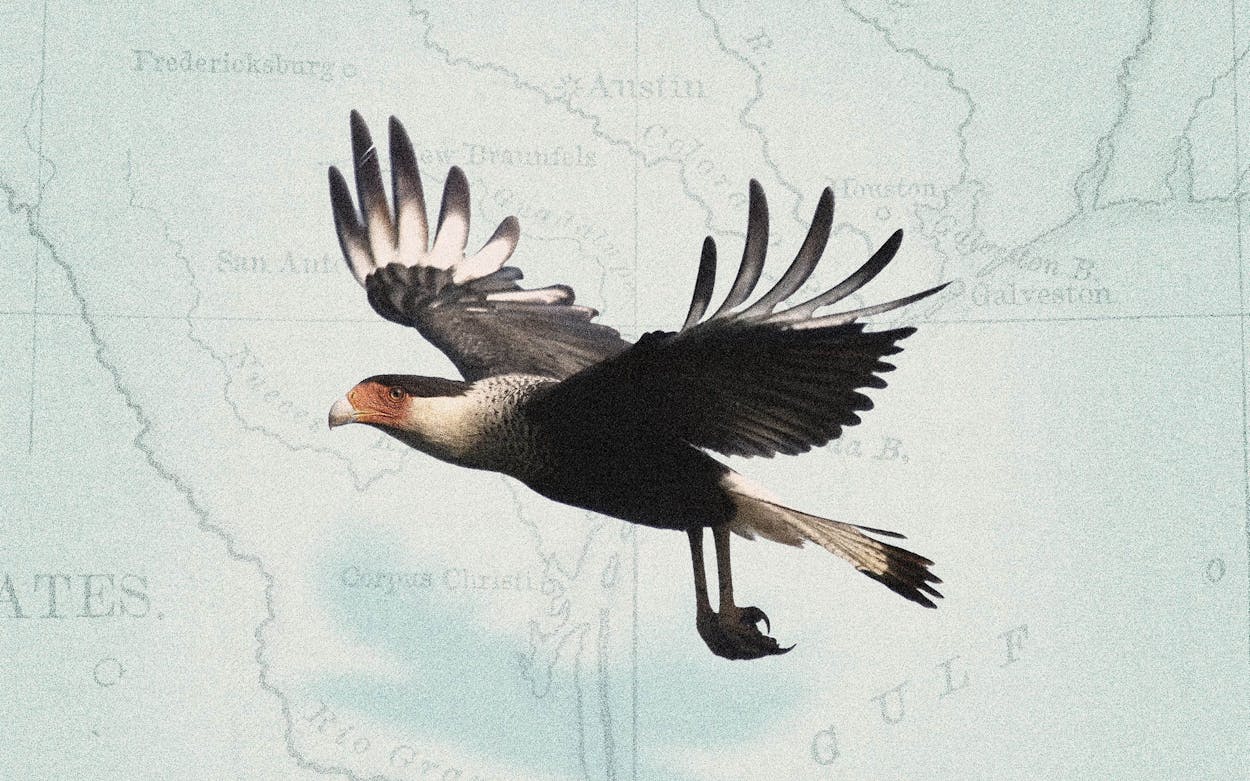

The caracara is a beautiful and fierce-looking falcon that ranges throughout Latin America and into the southern tip of the United States. Some people call them Mexican eagles. (They were sacred to the Aztecs, and one school of thought holds that the bird depicted on the Mexican national flag may even have been based on a caracara, not a golden eagle.) They have a flat, dark head with a scruffy crest in the back, and an ostentatious orange beak that hooks down to a sharp, blue point. Caracaras like to strut around on their unusually long legs, scratching for bugs or clawing at carrion, a favorite snack. Folks in South Texas are no strangers to caracaras, which often perch on power lines or fence posts and glide above dusty fields and roadways in search of dead hogs, armadillos, and other tasty carcasses.

The caracara’s typical range in Texas used to peter out by San Antonio. No longer. In the past two decades, the opportunistic birds have swept up the coast to Houston and into Louisiana. They’ve also taken up residence in the countryside around Austin and the Hill Country, and north of Waco through the Dallas–Fort Worth area. These days, it’s not unheard of for birders to spot caracaras just north of the Red River. Until the turn of the century, the only caracara strongholds in the U.S. outside of Texas were in South Florida and the Phoenix area.

When caracaras arrive in new territory, Cliff Shackelford often hears the news from excited, if slightly perplexed, ranchers. “This is a very conspicuous bird, so any landowner who’s got decent vision is going to notice it, because it’s large and flashy,” says Shackelford, the state ornithologist for the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department. “When you’re a longtime landowner in your seventies and you’ve never seen one on your property, you flip out.”

From a distance, he notes, people often misidentify caracaras as bald eagles because they have white throats and white patches on their tail feathers. And despite perpetual yet unfounded fears to the contrary, Shackelford adds, caracaras do not dive-bomb calves or lambs or even yippy Chihuahuas. Never mind the birds’ fearsome appearance. Caracaras don’t pose a threat to people, livestock, or pets. “They’re not a big, strong-footed predator that’s gonna grab the chickens and the dogs and, ‘Oh my gosh, my cat’s missing’—that’s not the case,” Shackelford says. “He’s really built to go after roadkill and is actually more like a vulture than anything.”

Why are the crested caracaras expanding their range northward? Like so many changes in the Texas wild, it might have something to do with the double wallop of climate change and habitat loss. The Audubon Society predicts that if average temperatures warm by just five degrees Fahrenheit, the caracara’s winter range will eventually consume every inch of Texas—other than the Panhandle, sorry—and will extend through a swath of the South and Southwest from South Carolina to San Diego. Surprisingly enough, a caracara even showed up in Canada a while back.

Caracaras prefer to live in savannas with a mix of open grasslands and stands of trees where they can perch and nest. With so much of Texas’s formerly wide-open grasslands turning into brush country as a result of overgrazing and a lack of prescribed burning, the birds could simply be on the lookout for more suitable habitat.

Shackelford, who first saw a caracara in Kaufman County east of Dallas in the mid-seventies, also wonders if the birds could be simply coming back to territory where they were hunted out by ranchers, some of whom wrongly assumed that caracaras were attacking their livestock. “Some have suggested the bird is not necessarily expanding north but is instead returning to its old haunts,” Shackelford says. It’s just a hunch, but it seems plausible. If nothing else, there’s more than enough roadkill to go around.

Until last November, Mike Vaught, an avid birder and rural mail carrier from Daingerfield, had seen just one caracara in his life, during a vacation at South Padre Island many years earlier. Then he was driving his mail route toward the tiny northeast Texas community of Leesburg, which he describes as a flat road with nothing but pastures, a few cows, and a few trees. That’s when he spotted a caracara.

“I almost did a double take,” Vaught recalls. “He was perched in a big ol’ gnarly dead tree in the middle of a cow pasture.” Vaught circled around to take pictures. When he shared the photos with friends in the East Texas birding community, he says, no one else recognized it.

That fall and winter, he often saw the caracara, always on or near the same dead tree in that field outside Leesburg. Then, one day near the end of January, the bird moved on. One of his buddies saw the caracara a few miles down the road.

Instead of soaring with the eagles, the caracara was content to share a field with a few black vultures, all of them munching on the same carcass. “It’s a strange bird,” Vaught says, turning reflective. “It’s a falcon, you know. You’ve got that kind of pedigree, and you’re gonna go hang with the buzzards.”