If you ask him to check a box, Peter Guzman considers himself a Democrat. Yet though he is now thirty years old, he has voted only twice in his life. In 2008, as a senior at McCollum High School on San Antonio’s South Side, where he and his family have lived for several generations, he heard an assembly lecture about the importance of voting. Inspired by the talk, and having just turned eighteen, he voted for Barack Obama, since the charismatic senator from Chicago was promising change.

Over the next eight years, even as Obama went up for a second term, Peter didn’t think too much about politics; he voted one more time, in the 2014 district attorney’s race in Bexar County, because some friends were working on the challenger’s successful campaign. It wasn’t until after Donald Trump’s election, in 2016, that he started paying more attention. “I just personally never liked the guy, and I was shocked to see that he was going to be our president,” he says. He began to ask himself: “Why is it good to be a Democrat? Why is it good to be a Republican?”

Peter didn’t know what either party stood for. Friends and family told him that based on his values, he was probably a Democrat. But he wasn’t sure what being a Democrat meant. So he began talking to the only person in his immediate family who did follow politics: his mother-in-law, Josette Salazar. He started watching the news on television and looking up CNN and New York Times stories on his phone apps. In July of last year, as he and his wife, Angel Marie, were waiting for the birth of their first child in the obstetrics ward of Southwest General Hospital, he and Josette watched hours of the Robert Mueller hearings together. Josette provided a running commentary that drew him deeper into the drama unfolding on the screen. She insisted to him that his vote mattered, and she urged him to vote again. As of this year, however, he still hadn’t. “That’s the thing,” he said, “I love reading about politics, I love watching it. But I haven’t been convinced to actually go out there and vote.”

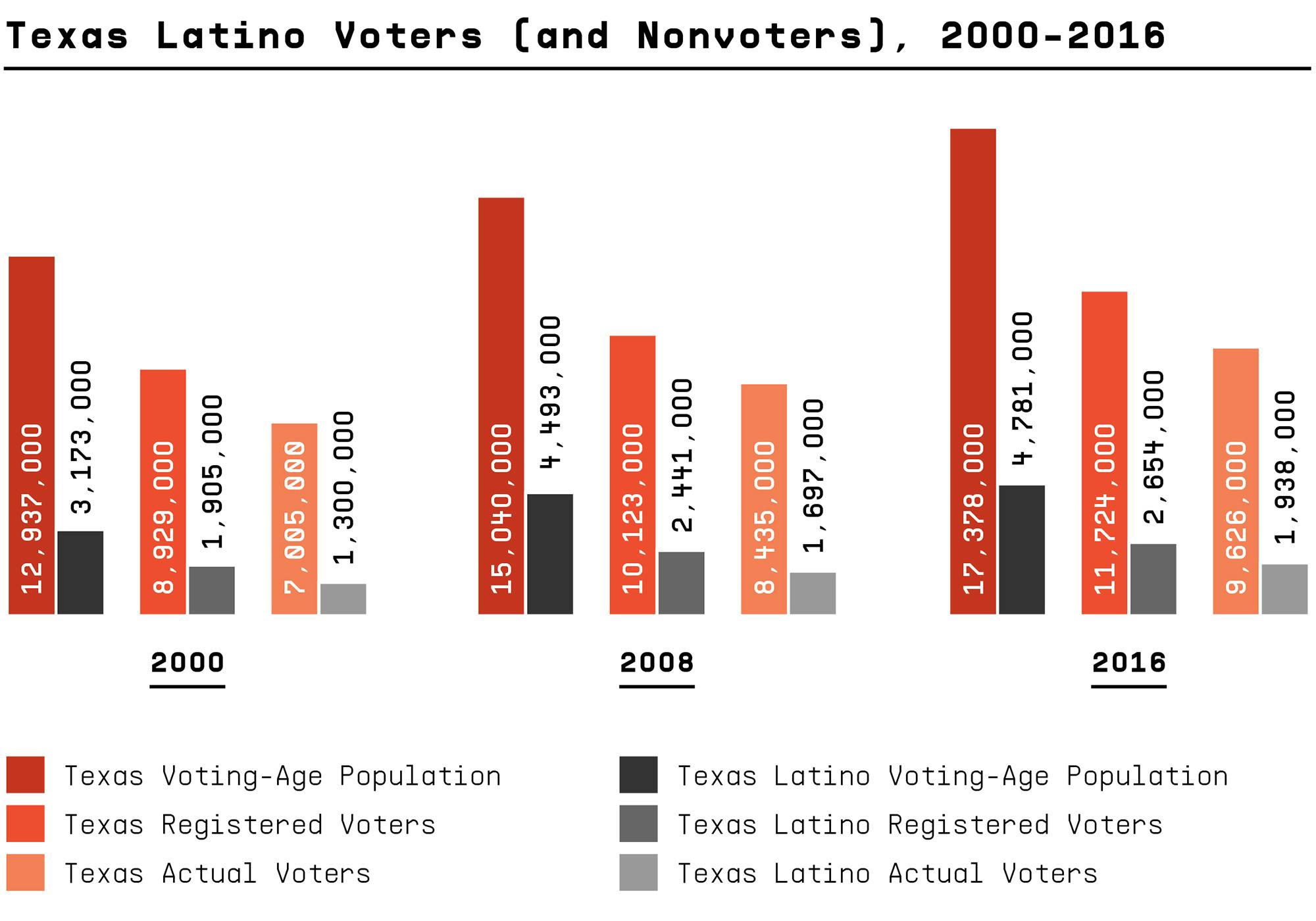

Peter isn’t alone. The question of why more Latinos aren’t voting has consumed politicians, pollsters, and political observers for the past few decades. Latinos make up about 30 percent of Texans who are eligible to vote but, in recent elections, only about 20 percent of those who actually cast a ballot. To be sure, Latino voter turnout has been increasing steadily. But Latinos’ presence at the ballot box still falls short of its potential. Next year, they are projected to become the largest demographic group in Texas. If they were to turn out in larger numbers, they could swing election outcomes in the state and—given Texas’s large role in the electoral college—at the presidential level too. This is the proverbial “sleeping giant” that, again and again, liberals have hoped will help them turn Texas blue.

But is “sleeping giant” the right metaphor to describe Latino voters? Are they really as disengaged as that phrase suggests? Or are there deeper reasons why many of them don’t vote? And, among those who do vote, why don’t more of them vote for Democrats, as liberals would like—and why are many voting for Donald Trump, a politician who has spoken of Mexican and Central American immigrants as murderers and rapists and as a serious threat to Americans?

Over the past year, in an attempt to better understand Latino voters and nonvoters, two colleagues—my fellow anthropologist Michael Powell and sociologist Betsabeth Monica Lugo—and I set out across Texas to get to know them. Instead of disseminating multiple-choice surveys, as pollsters do, we spent hours conversing one-on-one with more than one hundred Latinos who were eligible to vote, from five major regions—Houston, San Antonio, Dallas, El Paso, and the Rio Grande Valley. The study was commissioned and funded by the Texas Organizing Project Education Fund, the sister organization of the Texas Organizing Project, the largest grassroots progressive organization in the state. Though the group leans left, the study was nonpartisan, and we were given full independence to design it and let the results be what they may. While our research was focused on what drives civic engagement, not on which candidates Latinos prefer, many participants shared such thoughts with us in the course of our conversations.

We asked mostly open-ended questions, trying to get to the heart of the whys more than the whats of Latino voting. All of our interviews ran at least ninety minutes long, and some stretched to two hours. Many of the conversations turned emotional; more than one interviewee shed tears. We also laughed. The depth of the exchanges repeatedly surprised us, and much of what we heard ran counter to some of the most pervasive narratives about Latino voters and nonvoters.

Peter is a prime example. Here was a young man who reads politics voraciously and who spoke cogently about being racially harassed, about his views of representative democracy, and about his dreams for his then-eleven-day-old son. And who, it turned out, had even driven by the polls a few times during recent election seasons, but ultimately hadn’t felt compelled to get out of his car and cast a vote. Peter often told us that he wanted to feel like he was part of something bigger—something that would bring about change for his family and for his community. But he wasn’t convinced that voting would accomplish those things. Why was that?

Like many Mexican Americans in San Antonio, Peter has roots in his city and neighborhood that run deep. “Born and raised on the South Side, never left,” he told me proudly last August, when we sat down to talk. He’s a second-generation American on his father’s side and third generation on his mother’s side. He studied computer science at San Antonio College after high school, but left after his fourth semester because he no longer qualified for financial aid and already owed more than $20,000 in high-interest student loans. Since then, he had hopped between jobs, working as a grocery stocker at Walmart, a convenience store clerk, and, most recently, a billing clerk at a local produce company. Yet he never made more than $10.50 an hour. He sometimes supplemented his income by working at odd jobs such as mowing lawns, but he and his wife still struggled to get by, especially because he has chronic health problems and has amassed some $10,000 in unpaid medical bills. Peter has been diagnosed with prediabetes, diverticulitis, and high blood pressure, which sometimes cause him to miss work. But he said he can’t afford health insurance, which would cost him $132 a month under Obamacare.

Peter often told us that he wanted to feel like he was part of something bigger—something that would bring about change for his family and for his community. But he wasn’t convinced that voting would accomplish those things. Why was that?

He wanted to see the government raise the minimum wage and make health care affordable, but, like almost all of the nonvoters we spoke with, he didn’t believe that his vote could help make that happen. “I feel like what we vote for and what we say is not what [politicians] want to hear,” he said. “I would love to see why our vote matters. I want to see a presentation—I want to sit down and I want them to convince me, why is it great to vote?”

Peter was reflective about other factors that influenced his choice not to vote. He noted that virtually none of his family members have voted. “My mom’s not a voter, and my grandparents are not voters,” he said. “No one’s voted.” Voting, our study confirmed, is a habit that usually develops over time—more than a rational choice, it’s a social behavior that is learned and reinforced through example. Tellingly, none of the 24 nonvoters we interviewed grew up around parents who voted regularly. Studies show, and our research confirmed, that if your parents go to the polls when you’re young, chances are you will become a voter too.

We also realized that many of the nonvoters we spoke with didn’t have a lot of agency over their lives. Peter, for example, hadn’t been able to significantly improve his own situation, despite his efforts to get an education, work hard, and care for his family. Such feelings of financial stress and being overwhelmed seem to have a strong dampening effect on voting. We found a high correlation between income and voting frequency among those we interviewed—the more money you make, the more likely you are to vote. Some of the poor and working-class Latinos we interviewed were often struggling to respond to crises, and they focused their attention on the immediate issues they could make better. “Being poor really doesn’t lend itself to fixing major problems,” said Juan Flores, a 27-year-old nonvoter we interviewed in Brownsville. Government seemed distant, and many struggled to directly connect its policies and actions to their lives. The futility they experienced in other areas often paralleled how they spoke about voting and politicians. This may partly explain why the border regions and San Antonio—a city whose Mexican Americans have a long history of racial segregation and inequality—have lower Latino turnout than, say, Dallas or Houston, where there is more economic mobility.

Indeed, feeling empowered—and having a general sense of belonging—emerged as themes that repeatedly distinguished voters from nonvoters. Nonvoters tend to be surrounded by other nonvoters. They aren’t sure their vote matters, and they don’t feel that people in power care about their experiences or perspective. By contrast, voters often discuss politics with other voters. They believe they have a right to be heard, they are better able to directly relate government policy to their lives, and they believe they can influence political outcomes. It’s almost as if voters and nonvoters live in two different worlds.

One common misconception is that Latinos don’t vote in larger numbers because many of them are immigrants. But nationwide statistics show that naturalized Latino and Asian American citizens turn out at a somewhat higher rate than their U.S.-born peers. We observed that when a family doesn’t vote across multiple generations, the habit of nonvoting can become more entrenched. Nonvoting is an American problem, not an immigrant problem.

Over the past eight years, Texas has closed hundreds of polling sites, and some research shows that this disproportionately hurts Latinos. Only two of our interviewees mentioned voting hassles as an issue, however—and one of them managed to vote anyway, despite his usual polling place being shuttered. While making it harder to vote surely discourages voting, it didn’t seem to be one of the primary reasons our interviewees didn’t go to the polls. Those reasons were more deeply rooted.

But nonvoters—even those with strong doubts about the political system—can turn into voters. And this, too, we wanted to better understand.

People become politicized in many ways: through school, through work, by joining community or activist organizations, or even by watching political news that drives home the importance of voting. Nonvoters can be convinced to vote by politically engaged peers. And they can be moved to action by a personal experience that makes clear how specific laws are hurting them.

When we met Claudia Perez in the summer of 2019, she was 36 years old and doing full-time freelance administrative work for apartment companies. But Claudia, who lives in the same northwest Houston neighborhood of Spring Branch where she grew up, is also a full-time mom. She has four children, who now range in age from seven to seventeen, and she serves on the board of the PTA of all three of her kids’ schools. She is the daughter of Mexican immigrants, and her Panamanian husband, Jose, works in hotel maintenance. Together, they earn a modest working-class income that they manage carefully.

Like Peter, Claudia had not grown up around anyone who voted. Her parents, who are naturalized citizens, long thought that voting didn’t make a difference, based on their experiences of elections in Mexico, which they had regarded as corrupt.

At first, Claudia herself didn’t pay much attention to politics. But in 2003, when she was 21 years old and married Jose, she learned how immigration laws were hamstringing his life. Not only was he unable to attend his father’s funeral in Panama as he awaited his legal status, but applying for his residency turned into an onerous experience. “Even filling out the application was a whole ordeal,” she said. She enrolled in technical school to get a higher-paying job, because the government required that she earn a certain amount of money to petition on his behalf. “It’s just a lot of things that became very real.”

The next civics lesson came when Claudia’s children enrolled in school. She wanted to make sure they were getting the best education they could, so she started spending time on campus and soon learned how greatly the decisions that school administrators make affect their students. So she joined the PTAs. By the time I met her, she was serving as treasurer for one, secretary for another, and vice president for the third. When she invited other Latino parents to the meetings, however, they were reluctant to go. She realized that they didn’t feel like they belonged there or as if their views would matter to administrators. “They would be very surprised that you can really change what a principal is doing, or how they’re treating your children,” Claudia said. She started organizing potlucks and lotería nights where the winners walked away with gift baskets. “That’s how we got parents in. Trust me, they come.”

Claudia said that immigration and gun control were, for her, the most urgent policy issues at the moment, and she was highly critical of how Donald Trump has treated immigrants. When I asked her about the election, which was then still more than a year away, she laughed and said, “I know who I’m not voting for.”

Yet even though her policy interests and positions seem to align with those of the Democratic Party, and she has never voted for a Republican candidate, Claudia is not a Democrat. She doesn’t adhere to any partisan labels, despite the fact that she votes in almost every local, state, and national election. Instead, she assesses elections based on what issues she prioritizes at that moment and who she thinks is offering the better solution. “I can’t tell you that I’m a Republican or a Democrat,” she said.

Claudia reflected a larger and, to us, unexpected trend: Latinos often don’t identify in strongly partisan ways, even when they consistently vote for one party. Despite the intense, almost tribal partisanship that dominates politics in the country today, many of the voters we spoke with considered themselves independent. Numerous polls suggest that anywhere from 60 to 70 percent of Latinos identify as Democrats and 30 to 40 percent are Republicans—but those polls identify people by their ideological tendencies, even if they don’t formally affiliate with a party. By contrast, we kept finding Latinos who didn’t consider themselves to have an affiliation. And even many of the Democrats, and a few of the Republicans, said they were open to candidates and arguments from both parties.

There are several reasons Latinos aren’t highly partisan, we found. First, neither party historically has engaged them to a great degree—certainly not to the extent that the Democratic Party has targeted Black voters, for example, or the way Republicans have catered to evangelical Christians. The majority of people we interviewed had never been contacted by campaigns or met a political candidate, not even those individuals whose elected officials are Latino. They also felt a general disconnect with candidates and leaders, who they believed rarely understand or speak to their struggles, beyond the issue of immigration. Second, most Latinos don’t come from families where generations have voted for the same party (or voted at all), passing on that loyalty to their children. Third, a considerable number of Latinos hold ideologically mixed views on policy issues, from abortion to gun control to immigration, which can overlap with the positions of both parties. These are people who could, in theory anyway, be swayed by compelling arguments from either side of the aisle. And finally, we found a small group of mostly younger, college-educated voters who call themselves independent because they feel the two-party system has failed and isn’t properly representing everyone’s interests.

Many political observers and organizers expect Latinos to side with Democrats because of the party’s immigration policies. But across the political spectrum, we observed relatively moderate views about immigration. Hardly anyone we spoke with was calling for open borders—a policy that the Republican Party frequently claims Democrats and Latinos favor. Most of our interviewees empathized very strongly with migrants, but felt equally strongly that immigration needs to be legal and orderly.

Andrea Danielle Mata is a young independent from El Paso, but her views on immigration were reflective of the Democrats and Republicans we met with: “I would say there needs to be more regulation,” she said. “But you can’t have people wait for years and years and years to apply.” Following the law was important to most of the people we spoke with, but they also felt it was essential that the system be respectful of people and transparent, and that the government make it easier for some immigrants to come to the United States. Across party lines, they wanted Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals recipients to be fully legalized. And, while immigration was a top concern for many, it alone did not determine whether and how they vote.

Many Latinos hold ideologically mixed views on policy issues, from abortion to gun control to immigration, which can overlap with the positions of both parties.

Of course, despite the large number of independent voters we encountered, a majority of Latinos do vote Democratic. In general, the Democrats we spoke with talked about how the country and the government should provide opportunity to more people. Many were viscerally affected—even traumatized—by the recent separation of families at the border and by the 2019 shooting of 46 shoppers at an El Paso Walmart, which they blamed on anti-Latino racism they felt Trump has perpetuated. One 36-year-old woman in San Antonio broke into tears as soon as I began the interview. “I’m getting a little emotional,” said Monica Vega. “I think that this year, with everything that’s happened, I feel that our people should be voting, because it’s not right. Trump is supposed to be for the people, and he’s not. What kind of person allows people to be caged up like animals? We treat our dogs better than we treat people.”

Racism was a major theme in a number of our interviews, even if many people struggled to put a name to it. When pressed, almost everyone had experienced discrimination or had been treated differently due to their ethnicity. The message that Latinos don’t belong in society can subconsciously discourage them from voting. But it can also be a catalyst to get some people involved in the electoral process. Many voters told us that Trump’s disparagement of Latino immigrants made this a crucial election for them, and they felt more conviction than ever about voting.

And yet, for roughly every two Latinos in Texas who vote Democrat, one votes Republican—even when that Republican is Donald Trump. And these individuals are perhaps the least understood of all.

Angel Avila arrived to our interview in El Paso after a long day of work, apologizing for running a little late. Dressed in the dark coveralls of his trade, he gave off an air of quiet responsibility and respect. Angel, who was 25 years old that October, was in his fourth year of a five-year apprenticeship program to become a journeyman electrician, following in the footsteps of his father, a master electrician, and his grandfather. He is a proud member of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local Union 583.

“My plan was not to follow in my father’s footsteps, but that’s just how the chips fell,” he said, smiling. His parents, naturalized citizens from the Mexican border state of Chihuahua, are a poster couple for economic mobility. Starting with very little, they each earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees as adults and eventually settled in the verdant Upper Valley on El Paso’s West Side, where they live in a large, handsome brick home. Now it was Angel’s turn to work his way up the socioeconomic ladder. And he was working very hard at it; on top of his job, he was taking classes that he hoped would lead to an electrical engineering degree. He has a few learning disabilities that make schoolwork challenging, so he sometimes puts in double shifts with his tutor. (Since we spoke, he obtained his license and now works full-time as an electrician.)

Angel’s political awakening began in 2016, when he attended a Bernie Sanders campaign rally at the invitation of a friend, a DACA recipient who was volunteering at the event. When Angel, whose father is a Republican, heard Sanders speak, he realized he didn’t agree with what he was hearing. Sanders was saying the minimum wage should be raised to $15 an hour, but Angel wasn’t sure if the economy could support that, and whether that was fair to people like him. “Okay, you want to raise up the minimum wage, you want to help all these people out,” he said. “But I’m over here struggling day in and day out, paying my school out of my own pocket, and working my ass off just to be where I’m at. I’m not saying, ‘Don’t raise up the minimum wage.’ I’m saying, there has to be a fair number to raise it up to.” He did research on whether a higher minimum wage could impact small businesses. “Places get affected. They can’t pay their employees. It’s way too high, and a lot more people lose their job.” That November, Angel cast the first vote of his life—supporting Donald Trump for president.

There are many theories as to why some Latinos vote Republican. One common explanation is that they’re social conservatives who oppose abortion and gun control. Some left-leaning Latinos accuse them of rejecting their roots. And then there’s the theory, drawing on age-old stereotypes, that Latino men lean more Republican than women because of supposed machismo.

But our interviews didn’t fully bear these theories out. Certainly, we interviewed conservative Christians who are single-issue voters on abortion, but they were a minority among the Republicans we met. And the vast majority of our interviewees embraced their ethnicity and culture. As for the issue of machismo, many of Trump’s supporters said that they liked his toughness—but that group included women, and it’s not at all clear that this is any different than the attitude prevalent among his white supporters.

“Republicans represent the old-school American—make your own way, you sink or swim,” Angel explained.

Instead, what most commonly distinguished the Republicans we spoke with from more liberal Latinos was their view of the meaning of opportunity, and the government’s role in creating it. They tended to speak about limited resources, and they questioned whether the government providing money and other forms of assistance to the less-well-off would affect their own well-being. Many of them did feel that the government should offer support to certain groups such as the elderly, but for everyone else, they wanted public assistance to be temporary and not become a way of life. Particularly in El Paso and the Rio Grande Valley, Republicans and even many Democrats spoke critically about individuals they feel are gaming the system by accessing benefits they’re not entitled to. Angel offered the example of residents from Ciudad Juárez who he said get financial aid at the University of Texas at El Paso despite coming from middle-class families, since the school doesn’t verify their parents’ income.

Government leaders, Angel said, “want to give, give, give, but who are you taking from? You’re taking more from the middle class.” He added, “I’d rather hold my head up high than ask for a handout—and I understand that people do need help. But I see that a lot of people take advantage of that system.”

Among several younger, working-class men we interviewed, the sense of having to compete in the job market with immigrants was also a very real concern. They admired immigrants’ work ethic and skills, but one of them said that immigrants are easier to take advantage of because their legal status makes them vulnerable. “If you were a boss and you headed a company, would you pay me one hundred dollars, or would you pay five other people twenty dollars?” said another young man, Fernando Morales of San Antonio. In Angel’s experience, the competition came from unlicensed electricians who were trained in Mexico, which is why he was thankful that he was part of the union, which offered wage protections and benefits. He conceded that the Republican Party isn’t particularly supportive of unions, but he said that his coworkers vote for both parties.

Angel also identifies as a Republican because he staunchly supports gun rights. He owns several guns, including an AR-15, which he uses to target shoot, like a number of other El Pasoans we interviewed. “I feel like what we need to do instead of trying to take guns from people is teach people how to respect the weapon,” he said. “That’s the big thing my dad showed me and my sister.” He believes that people who want to cause harm will get their hands on weapons whether the weapons are legal or not, and he noted that in Mexico, guns are common despite being outlawed.

In short, the attitudes and values of Republicans resonated with Angel, as they did with his father. “Republicans represent the old-school American—make your own way, you sink or swim,” he explained. He was satisfied with Trump’s performance on the job, even if he didn’t agree with everything the president says or does. “I like more of his business side,” he said, echoing other Republicans we spoke with. “I don’t like how he speaks, but he follows through on everything he says. I like that I know what I’m getting.” As for Democrats’ accusation that Trump is a racist, Angel replied, “I think everybody’s racist, in a way. But I don’t feel like he’s super racist.”

Like Angel, many of the other Republicans we interviewed had supported Trump in 2016 because they liked that he wasn’t a career politician and that he called things as he saw them—even if some felt he is often too brash or crass. One 36-year-old Republican woman in San Antonio who asked for anonymity said the only way for Trump to fix the country’s problems was through “hard love” and “putting his foot down.” As for his immigration policies, we met one El Paso Republican who didn’t vote for him in 2016 because he felt insulted by the president’s disparagement of Mexicans and didn’t plan to vote for him this year, either, because of his treatment of immigrant families at the border. “I can’t vote for a president that looks down on me because I’m Mexican,” he said. “Who I truly and genuinely believe is a racist. I couldn’t do it.” But most other Republicans we spoke with remained loyal to Trump. They did not take his comments about immigrants seriously or personally, even if they came from immigrant families themselves—and they felt the media often took his words out of context.

These voters may have disagreed with some of Trump’s policy positions and personality traits, but they felt that his overall values aligned with their own. And they didn’t feel the Democrats were giving them better options.

So what sense do we make of Latino voters? When my colleagues and I launched our study more than a year ago, we were eager to complete our first set of interviews in Houston, thinking that would get us closer to answering this question. But every one of those 21 conversations seemed to open up a new set of ideas, a different angle on the issues we were hoping to clarify. A wise Spanish proverb came to mind: cada cabeza es un mundo (“every head is a world unto itself”). This seemed eminently true about Latino voters, as it likely is about all voters: The groupings and labels we create to talk about U.S. politics and to drive electoral outcomes are loose constructions that obscure the many ways that citizens make sense of their government and the issues they care about. Latino voters are not a monolith. We didn’t find a single way of being Latino—much less a Latino voter.

One common thread we did find is that Latinos are by and large informed, independent political thinkers, whom our political system hasn’t properly understood or engaged. And making that happen begins with something quite simple: listening. We were surprised by how powerful this tool turned out to be. It’s what we regularly do as social scientists, and what I do as a journalist. But in the realm of representative government, it’s sorely missing. For many of our interviewees, just being heard was visibly empowering. And though we were there only to ask about their views, not to encourage them to vote, a few nonvoters we spoke with cast a ballot in this year’s primaries—motivated, they said, by the conversation we’d had months earlier.

As for the sleeping giant metaphor, my colleagues and I came to see it as vastly misleading. Latino voters aren’t “sleeping”—most of them are following politics, and they voiced strong personal opinions when we created space for those opinions to be heard. Many of them simply don’t feel like full citizens or players in the system. They won’t “wake up” and mobilize overnight when the right candidate or election comes along. They are a constituency in the making, gradually being engaged by the political system and empowered in society.

“If you’ve taken the time to see what Hispanics really want, all they really want is somebody to listen to them,” said Claudia, who had been the first of our 104 interviewees. “You might not even be what they want in a [candidate]. But as long as you listen to them and give them that attention and respect, they’ll respect you just for that. And you might even get their vote.” Claudia’s sermons made an impression on her parents, too, and with her help, they registered and voted for the first time in 2004. Now they eagerly follow political news and ask her when the next election is coming up so they can make their voice heard.

As for Peter, he, too, is now thinking differently. Our interview last year had prompted him to reconsider the importance of voting. Previously, he’d concluded that the Electoral College made his vote meaningless—Hillary Clinton’s loss to Trump despite winning the popular vote made him cynical. But now he was open to persuasion again, especially since, given his health struggles, the coronavirus pandemic had left him feeling vulnerable and exposed. After reaching out to his mother-in-law and a couple of friends, he finally decided that this is the year he’ll go back to the polls. “I’m able to change my mind about voting,” he told me. “I would love to see somebody that has the knowledge and the responsibility to be in the office help our nation out once again.”

The quotes in this story have been edited for clarity and space.

This article originally appeared in the November 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Don’t Call Them the Sleeping Giant.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads